Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

An extended anecdote tells that around 1920, in an exhibition in A Coruña that showed the prints of Castelao that were going to make up the album Nós, someone asked the artist why he was painting a Galicia wrapped in drama when there were so many beautiful landscapes and parties that could serve as inspiration. “Well, because I don’t have a vocation for drugs,” was the answer[1]. The album Nós establishes a critical trend in art and opens a crack that the next generation, the Renovadores, will widen by taking up the social function of Castelao’s art and adding to the identifying perspective of Galician art the influences of international art and the avant-garde. A renewal committed to the republican ideals, which runs intensely until the beginning of the Civil War.

It is not surprising, then, that Castelao is the artist with whom the Carlos Maside Museum begins to reconstruct, in 1970, the history of Galician art in that exercise of recovering historical memory that formed part of the ideology of the Laboratorio de Formas; the ambitious program of restoration of Galicia’s past after the process of dememory suffered with the war of 1936. Conceived by Isaac Díaz Pardo and Luis Seoane during their meetings in Republican exile, the Laboratory is the institution that condenses the lines of thought on which the Sargadelos group was formed, a great industrial and cultural project of Galicia that would become an example of the regulating character of utopia, of the moral ideals that encourage us to do or transform. A metaphor of creation linked to the transformation of society, of culture as a motor for the reactivation of memory, identity and territory.

When in the 1950s the strength of the exile from Galicia coincided in Buenos Aires, that “collective brain” – formed by Luis Seoane and a newcomer Díaz Pardo, accompanied by Arturo Cuadrado, Rafael Dieste, Lorenzo Varela, Blanco Amor and others – set in motion a plan to reactivate cultural activity in Galicia, starting with the recovery of the memory silenced by the Civil War and the institutions destroyed by the dictatorship. Moved by the commitment, they collectively imagined the foundation of an industrial and cultural structure, with a moral and social dimension, to reinvent the country.

Díaz Pardo had arrived in Argentina in 1955 to create, in Magdalena, a ceramic factory as an extension of Cerámicas do Castro, inaugurated at the end of the 1940s in Sada (A Coruña). In the Argentinean diaspora, where the world that had disappeared in Galicia in 1936 was surviving, he set up with Luis Seoane the foundations of what would become Sargadelos, a multi-faceted company characterised by that moral and experimental dimension that explains its appearance, o re-founding, in some cases, of the Sargadelos factory, the Carlos Maside Museum, the Galician Information Institute, Ediciós do Castro, the Xeological Laboratory of Laxe, the Sargadelos Seminar, the industry and communication laboratories, the ceramics schools, etc.

The Civil War and the prolonged dictatorship applied a damnatio memoriae that meant the elimination of the immediately previous projects that demanded the construction of a Galician political and cultural space. This annihilation of thought led to the creation of the Carlos Maside Museum as an archive that “aims to collect the work and documentation of the movement for the renewal of contemporary Galician art with its social environment prior to the civil conflict of 1936, becoming the center of aesthetic ideas of Galicia and the universal movements of art,” according to the manifesto of the Laboratorio de Formas[2].

The Carlos Maside Museum was inaugurated on 18 May 1970 with 120 pieces that articulated the story that Luis Seoane had been defending in his analysis of Galician art, in which he placed Castelao as the precursor of the Renovadores[3]. This is the possibility of the Galician art that Seoane tries to historicize and to contextualize with the projected in the emigration – “Galicia includes, for centuries, to the places where the Galicians emigrate collectively”, he affirmed- and with the European art, because the generation of the Novos reconciled the own thematic with the contributions of the European contemporary painting. The story formulated by Seoane, the main creator and promoter of the Museum in its first phase[4], is configured as a counter-history that deconstructs the present returning to the remote moment, understanding, from very early on, the need to overcome the fractures of the recent past since the restitution of historical memory.

Aware of the debates that were taking place in the field of international museology, Seoane understood the museum as a dynamic and critical place: “A museum today is not exactly an institution that agrees with the past without judging it and with the present without subjecting it to criticism”[5]. She also expressed her interest in integrating the arts into everyday life when she stated that “the Carlos Maside Museum must be a center of cultural activities for the future that are useful for the distension of the artistic knowledge of our people”[6] and that it must serve “an educational policy (…) It is not only about the useful architectural work that can be done, with all that a museum of our time demands, but that the museum serves the community”[7].

This discourse has its roots in the values promoted by the museum in interwar Europe. After World War I, museums reflected the social and cultural changes demanded by the anti-bourgeois movements, and their directors transformed the elitist nineteenth-century temples into places of learning, contributing to the atmosphere of experimentation that reflected the spirit of the 1920s. Furthermore, these debates were also manifested in the Bauhaus of Gropius, one of the references that are hidden in the ideology of the Laboratorio de Formas and that the founders of Sargadelos assumed as an archetype. The development of the Carlos Maside Museum project is based on other experiences that Seoane himself mentions in the letters sent to the Museum’s Board of Trustees on 2 March 1979:

As an antecedent to what we call the static and dynamic functions of the Carlos Maside Museum of Art, which generally influenced my work, we must take into account the Art Train set up by the Russian constructivists, futurists and abstract artists at the time of their revolution, the plans they left behind for Art Schools, exhibitions, etc., Ángel Ferrant, Gabriel García Maroto and Manuel Abril in the 1920s; Herbert Read and Schmidt, later Director of the Basel Museum, etc., and the experience transmitted orally in my case by Rafael Dieste, by the pedagogical missionaries of Spain, founders of a mobile museum with copies of works from the Prado Museum, giving conferences on them by the Spanish people[8].

Although the ideal project was frustrated after two years of intense activity (1970- 1972), we know from Seoane’s texts that the museum design he devised divided its functions between static and dynamic[9], programming lectures, organizing screenings and creating a hut to exhibit works of art and give lectures for the Galician people. This circulating version of the museum, which did not materialize, was a clear homage to the experience of the Resol hut, founded by Arturo Cuadrado in the 1930s, and the traveling theater group La Barraca (1931), designed by Federico García Lorca.

The members of the Laboratorio de Formas, when thinking about the Carlos Maside Art Museum, didn’t want this to be just something static, unmovable, waiting for the fans, and the people in general, to come to it. To avoid this, as a branch of the Museum, they founded a Barraca with their name, Barraca Carlos Maside, which would travel around Galicia, stopping at important towns, and where exhibitions organized by the Museum would be taken to the public, either made with works from the Museum’s collection or inviting groups of artists to exhibit there. [10].

These are lines of work of a rare modernity, taking into account the moment in which they were designed, in the final stretch of a dictatorship whose artistic asepsis had isolated the Spanish territory for decades from the debates on museology and museography that had been taking place in institutions such as ICOM since the 1940s.

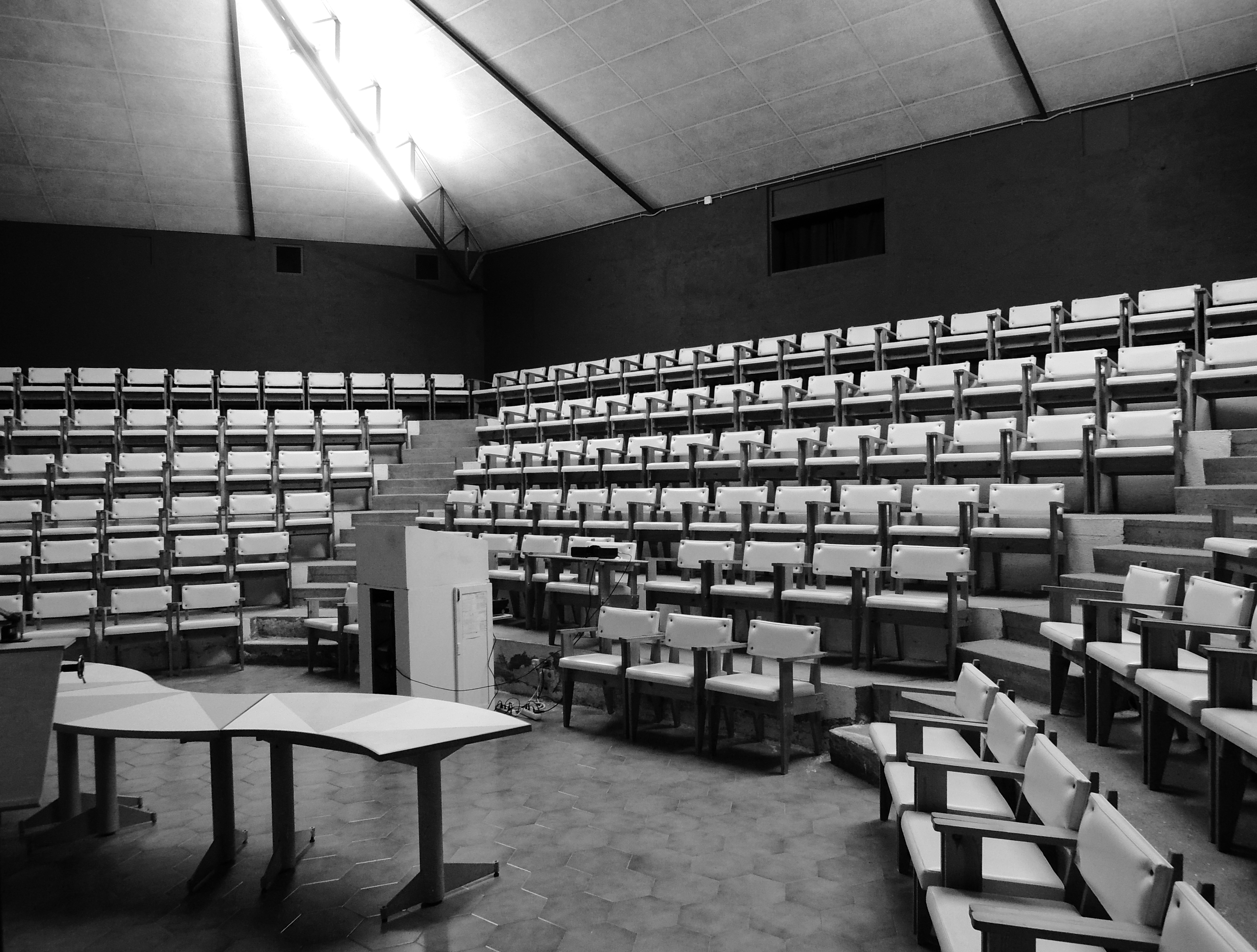

Photograph by Misha Bies Golas

The Carlos Maside Museum, whose artistic direction was entrusted to the Laboratorio de Formas -a symptom of that collective feeling of the project’s promoters-, organized the first exhibitions in Galicia of Picasso, Miró, Grosz, Alberto and Bertolt Brecht, among others. In 1970, Xosé Díaz Arias, who was barely twenty-one years old, took over the organization of the museum and the film sessions, which were scheduled uninterruptedly between September 1970 and June 1972. He organized film sessions such as those of Norman McLaren -Scottish-Canadian experimental filmmaker to whom the Carlos Maside Museum dedicated an anthology on August 31, 1971-, the screening of Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, sessions on Le Corbusier, Picasso, the experimental films of Poland’s Jan Lenica, the Germans’ Walter Ruttman and Hans Richter, and the Yugoslavian Vlado Kristl.

Luis Seoane accompanied and encouraged, enthusiastically, in Buenos Aires, the work of Xosé Díaz at a time when there was hardly any cultural activity in Galicia. The attendance was beyond the capacity of the museum, and the sessions were always full. This is how Seoane wrote one of the radio broadcasts of the program Galicia Emigrante a few months after the opening of the museum:

On the other hand, international art films are shown every week in one of its rooms. Since June, two films have been shown on German expressionist painting, Pablo Picasso, Emil Nolde’s watercolors, “Man and Mask”, on the ballets performed by Oscar Schlemmer in 1919, “40 Years of Experiments in Film” including abstract attempts by Hans Richter, a film on the Bauhaus, another on the architect Le Corbusier and, apart from that, one on the chapel that this architect built in Ronchamp, France, near the Swiss border. Admission is free and each attendee is given written information about the film being shown, regardless of the news that originates from the questions and answers that follow the screening. […] Conferences and film screenings are part of what was projected for the future of this Museum but, even so, they can give an idea, to the general public, of the level that its founders intended, trying to create a cultural center displaced from the city that would have as its first support that of the peasants, workers and fishermen who are its neighbors and who today feel proud of the Carlos Maside Museum”[11].

Photograph by Misha Bies Golas

Although the initial objective of the museum had been to recover and study the renewal movement of Galician art, the collection was extended over the years with the intention of housing a representation of contemporary Galician art. The patrimony that it guards, originally formed by donations from the private collections of the founders, was increased thanks to pieces bequeathed or deposited by owners of significant works and by representatives of Galician culture in exile [12].

In 1982 the museum’s collections were moved to their final location, a building designed by Andrés Fernández-Albalat to house the permanent collection[13]. Without Luis Seoane, who died in 1979 after gradually moving away from the museum due to differences in its operation, it was Isaac Díaz Pardo who supervised the installation of the collection in the new building, organized the rooms, the museography and reconstructed the history in the posters and texts that remain in the space almost four decades later.

Today, a certain legal void complicates the protection and conservation of the important heritage it treasures, a great archive of our memory. There are hundreds of works, among them twenty-two masks designed by Castelao for the premiere of the play Los viejos no deben enamorarse, on August 14, 1941 in Buenos Aires. It is an duty to protect them; they are our history. So important for understanding the present.

Photographs by Misha Bies Golas

(Featured Image: Photograph by Misha Bies Golas)

*This text, translated and revised by the author, was originally published in Grial: revista galega de cultura, ISSN 0017-4181, Vol. 54, Nº. 209, 2016, págs. 127-137. The original, more extensive, Galician version can be found here

[1] Recreated in O Movemento renovador da arte galega no Museo de Arte Contemporánea Carlos Maside, Sada, Ediciós do Castro, 1990, p. 5. There are not enough elements to date or place the anecdote, but according to the researcher Miguel Anxo Seixas Seoane, the first written reference to this anecdote is attributed to Xosé Núñez Búa. With the pseudonym J. D’Arousa, publica “Anecdotario galego: Co gallo de Nós” en Galicia Emigrante 32, December 1957-January 1958, p. 36.

[2] Manifesto consulted in VV. AA. Sargadelos recuperado. O Laboratorio de Formas 40 anos despois, A Coruña, Fundación Luis Seoane y SECC, 2008, p. 60. Exhibition catalogue.

[3] ] “A rather conceptual precedent, an ethical and thematic initiator, rather than a formal antecedent of the Galician Art Renewal Movement”, as Lino Braxe and Xavier Seoane point out in Braxe, Lino; Seoane, Xavier. Luis Seoane: textos sobre arte, Santiago de Compostela, Consello da Cultura Galega, 1996, p. X.

[4] “(…) the idea of the Carlos Maside Museum, as well as its structure, the direction of its installations and its orientation and selection correspond entirely to Luis Seoane. It is an old idea that he had already expressed before the laboratory was born. He is also responsible for the greatest contribution to the work”. Díaz Pardo, Isaac. “Algunas precisiones sobre el Museo Carlos Maside”, en La Voz de Galicia, 26-VIII-1971.

[5] Seoane, Luis. “Notas encol do arte galego e sobre o Museo Carlos Maside”, en Cadernos do Laboratorio de Formas 1, Sada, Ediciós do Castro, 1970, p. 32.

[6] Ibid., p. 19.

[7] Letter from Seoane to the members of the board of trustees of the Carlos Maside Museum (2- III-1979). The one addressed to Díaz Pardo is reproduced in Díaz, María América. Luis Seoane. Notas ás súas cartas a Díaz Pardo 1957-1979, serie Documentos 186, Sada, Ediciós do Castro, 2004, p. 728. Una carta igual se la dirige Seoane a Fernández del Riego (2-III-1979). Epistolarios de Luis Seoane, Santiago de Compostela, Consello da Cultura Galega, 2014. It can be read here

[8] Ibid.

[9] Seoane was familiar with the various types of museum that appeared, above all, as a result of European cultural reconstruction after World War II. He probably based the project of the Carlos Maside Museum on the functioning of the Kunsthalle, perhaps that of Basel, which he considered “a model institution” in terms of both content and form of organization within the group of museums in the city of Basel. See text “The Kunsthalle in Basel, exemplary organization of art”, in Braxe, Lino; Seoane, Xavier. Luis Seoane: textos sobre arte, cit., p. 435.

[10] Seoane, Luis. “Notas encol do arte galego e sobre o Museo Carlos Maside”, cit., p. 29.

[11] Seoane, Luis. Text for the radio broadcast of Galicia Emigrante (8-XI-1970). Legacy of the author in the Fundación Luis Seoane, A Coruña.

[12] Certificates of legacy or deposit with the data of the persons and entities that gave the pieces, with the conditions under which the delivery took place, are kept in the private premises. If the Carlos Maside Museum is dissolved at any time, “they will be returned to the entities, persons or their heirs in the first degree who had transferred them, and those that have been bequeathed will be handed over to the Galician Museums”, as stated in the notarial act signed before the notary José Luis García Pita, (9-II- 1970), en A Coruña. Protocol number 324/1970.

[13] The museum is formulated as a structure with a hexagonal base with rooms with the same polygonal shape, joined together and designed to be able to add new units in the future. They are distributed around a central module with a staircase and a luminaire that provides zenithal light.

Agar Ledo (Santiago de Compostela, 1975) trained in Art History, Museology and Political Science at the University of Santiago de Compostela and at Goldsmiths, University of London. Between 2006 and 2018 he was in charge of exhibitions at MARCO (Vigo). She currently works at the Department of Collections of the MNCARS.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)