Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Admired for his inventiveness and eccentricity by film director Nacho Vigalondo, by Ángel Sala (director of the Sitges International Fantastic Film Festival of Catalonia), and by several experts in Hispanic subculture featured in Olaria (the documentary on his life and oeuvre, still in production), Juan Carlos Olaria (Saragossa, 1942) is an exceptional figure in the context of Spanish cinema. His filmic adventures, amateur improvisations with rudimentary special effects in which he played the roles of producer, actor, cameraman and prop manager, have already acquired a cult aura. They even won him the somewhat stigmatising motto of being ‘the Catalan Ed Wood’.

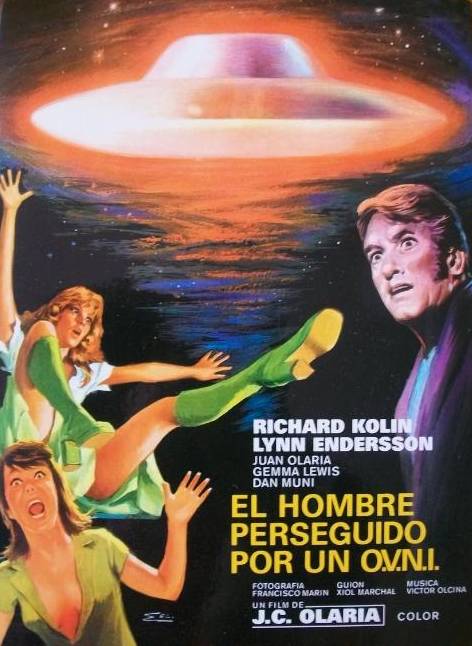

In 1976, after having shot several short films, Olaria released his only feature film. For many, The Man of Ganimedes is the first film on aliens made in Spain. El hombre perseguido por un ovni (its original Spanish title, literally ‘The Man Pursued by a UFO’) was shot between 1972 and 1975 and financed by his father, who also appeared in the film. In spite of being a forerunner, however, Olaria’s works were commercial flops and consequently decided to stop directing. Until now. For two years he has been shooting the second part of this feature film, which will be titled El hijo del hombre perseguido por un OVNI (The Son of the Man Pursued by a UFO), starring the critic, screenplay writer and actor Tony Junyent, who accompanied him at a talk with the audience held Thursday 7 September at Espai Quiró.

Amidst the urban density of uptown Barcelona, a body of land opens up in the middle of the closed forest of cement — Espai Quiró. Opened in January 2015 and run by different neighbourhood bodies, it owes its name to its proximity to the former Quirón Clinic. Set up by Infancia en escabeche, an organisation dedicated to discovering talent and revisiting films considered ‘sins of youth’, the season entitled Filmic Pubertal Pollutions (PPF, for its initials in Spanish) was held outdoors, despite a sporadic drizzle, before stands made of wooden pallets. On this occasion, it paid tribute to Juan Carlos Olaria for ‘the scant means, rudimentary décor and special effects that would rouse the onanist impulses of Wes Anderson and Michel Gondry’, as announced in the programme. After a short introduction by the organisers of the film season, a number of short films were screened, as we shall now see.

Robo al amanecer (1957, 7 minutes, black and white, silent, 8mm) is a noir detective story that the director shot when he was barely fourteen, and in which he simultaneously played the three leading roles. Also inspired in Neorealism, Grandes rebajas (1962, 5 minutes, black and white, sound, 8mm) reveals the context of mass internal immigration in the Catalonia of the sixties, with the increase in slums, overcrowding and crime. However, the relationship between a shop assistant at a haberdashery in the Guinardó neighbourhood and a customer with an unusually extreme desire for socks is cheeky rather than mundane. Also inspired in Neorealism, the short film, Principio del Nirvana (1964, 15 minutes, black and white, toned to monochrome colours with chemical baths) expresses a radical change in mood. Here, Olaria presents a sort of existential psychodrama looking into the typical tribulations of a young man who attempts to commit suicide by throwing himself on the railway tracks.

Nevertheless, the passion of this film director was science-fiction, the genre that demonstrates the candidness of his unbridled amateurism. The favourite short film for many of his fans is El planeta Plinio (1958, colour, sound, 8mm). Filmed on Barcelona’s Bare Mountain (El Carmel) and featuring the director and his baccalaureate colleagues, this is perhaps his fans’ film, a hilarious interplanetary journey full of adolescent candour and, of course, cardboard monsters and rockets. In this path of speculative fiction, consequence of the paranoid time, ¡Mil bombas! (1961, 10 minutes, black and white, sound, 8 mm), is a short political fiction film about nuclear hysteria during the Cold War characterised by a certain impetuosity that evokes Bergman’s The Seventh Seal in tension, with a profusion of unexpected comicality that verges on improvisation and slapstick. The film won the Stimulus Medal awarded by the Catalonia Hiking Centre (CEC, for its initials in Catalan). Finally, unlike most of his short films, in Hormiga (1964, 7 minutes, colour, sound, 8mm) Olaria transfers his gaze from the sky and outer space to the Earth. This mini-documentary is devoted to the behaviour of ants and other insects; observing them produces an effect of a puzzled gaze, as if the insects responded to the physiognomy of the aliens the director was unable to produce in his films. This work won him the Amateur Film Festival Award, the greatest artistic recognition he had received so far, granted by Italian minister Achile Coron in the Aldo Moro government.

For decades, the almost unlimited possibilities offered by digital technology applied to the audiovisual field have fostered a return to the handcrafted origins of the seventh art, a revival of the DIY filmmaking promoted by the talented Michel Gondry, Spike Jonze and Wes Anderson, who revisited the handcrafted materiality inaugurated by Méliès. The attention that the work of forgotten Olaria has received in recent years is therefore not surprising: interviews in Spanish and foreign media, a documentary on his life and oeuvre still being filmed, besides the publication of The Man of Ganimedes (1976) by L’Atelier producers in 2007 to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of its release.

In The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love (Verso Books, 2017) Harry Merrifield tells us that the term amateur (a snobby Gallicism for non-professional) encompasses a criticism of our contemporary culture of labour. Merrifield mentions the works of Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Canadian town planner and activist Jane Jacobs, and philosophers Edward Said and Guy Debord as examples of non-professional thinking that classes them as radical post-disciplinarians. As in the case of the films by Juan Carlos Olaria, the term amateur defines impassioned non-aligned citizens opposed to the mechanical professionalisation that contemporary society demands from us. According to Merrifield, as obsessive enthusiasts they represent values that need to be defended and, in the case of our auteur, candour and zeal in directing, over and above the end results. In the incipient cultural industry of a country immersed in the postwar, his compulsion for film and his extravagant themes, first expressed at an early age, shaped a naïve oeuvre that was ill fitted to such an obvious craft. Perhaps involuntarily, his work resisted professionalisation and technical formalism, and his amateur compulsion prefigured an inaugural reaction to the hyper-specialised capitalism of the twenty-first century.

Ana is fascinated to dive into books and movies, to approach with caution those tentacles that lie in the depths and to return to count what she has seen. She has published “Este es el momento exacto en que el tiempo empieza a correr” (Premio Antonio Colinas de Poesía Joven), the novels “La puerta del cielo” and “Hemoderivadas”, “Constelaciones familiares” (short stories, Premio Celsius Semana Negra de Gijón) and “Érase otra vez. Contemporary fairy tales” (essays). She currently lives and works between Berlin and El Paso, Texas, where she is a Bilingual MFA Fellow in Creative Writing at UTEP. Some of her texts have been translated into Portuguese, Italian, Polish, Lithuanian, German and English.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)