Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

I was invited to write about obsolescence and ruin in my own artistic practice, which is cinema, and it is inevitable to connect this to the material of film, which is the medium in which I work to capture light and time. And since ruin and obsolescence deal precisely with “what happened,” I have decided to begin with an exercise in memory.

I belong to a generation that in technological terms represents a kind of hinge. We learned to film on celluloid at the very time of its decline, when the (supposed) digital revolution seemed as if it would dismantle everything we had learned. In those formative years there was neither enough time nor distance for nostalgia to arise for something that we knew would be lost sooner rather than later. Thus, we were perfectly aware that we were learning something that was doomed to uselessness.

The useless is precisely that which does not produce profit, service or benefit, and film material in utilitarian terms is an inconvenience. The difficulties are undeniable. A scarcity of artifacts and spare parts due to the evident decrease in its production, a dependence on declining industrial production and therefore a rise in costs, difficulties in its reproduction, limitations in its diffusion and, consequently, meager productive prestige, all relegate it to the margin.

Why then work with a language that is based on a technology that has been declared obsolete? Well, precisely because its outdated characteristics, in contrast to digital novelty, make other images possible, but also, more than anything else, because they allow for another correlation. Film material is today a singularity that contradicts the enthusiasm for digital immateriality and that is one of the reasons for its vindication. In the digital present, going against the current involves an act of resistance, not necessarily a resistance to change, but rather a disagreement with the narrative that defines it, that is, change as development, progress and improvement. Obsolescence represents a kind of antithetical character to the global project called progress, since its residual condition after its passage from the avant-garde to the rear-guard contains within it the problems of its disenchantment. This degradation, although it seems a disadvantage, frees obsolete materials from the dictates of the market, and the people who make use of them, or those who still need them, safeguard them and ensure the maintenance of the structure that supports them. Celluloid, for example, not only resists thanks to large studios (which continue to support their digital productions on photochemical media), film libraries and archives, it also survives thanks to a network of people, groups and artists who organically restore the disappeared services after every blow the market inflicts. The obsolescent condition is capable of generating refractory tissue.

Obsolescence is in contemporary times a condition to avoid if what you want is to express precisely the opposite, validity. The disadvantage that the obsolete denotes is born as a result of a kind of desynchronization with its environment, and the more that incompatibility increases, the greater its insubordination. This decrease in utility is forced upon it by the same system that has produced the object in question, since its replacement is necessary to feed the productive machinery. Obsolescence is nothing more than the label that the productive system places on goods that lose the splendor of novelty. This mechanism was perfected during the last century and today so-called programmed obsolescence projects the useful life of goods in order to control and plan their long-term production and thus create a market dependence.

In the neoliberal paradigm of production that governs culture, movie theaters and museums are laboratories of ideas, languages and new media. The opposite, that is, the old, acquires testimonial legitimacy there. Just as merchandise needs to be novel to attract interest, audiovisual works are often subject to the logic of bigger is better. Sharper, brighter, and bigger images are better, or so the slogan suggests. If the obsolete already has enough difficulties to coexist with the contemporary in the cinema or in the museum, where the political is enunciated (also) from criticism towards any attempt to standardize and homogenize, outside the limits of culture the obsolete is already considered an anomaly. Nonetheless, there is a trend today towards the use of second-hand technologies and consequently of all that is anachronic and obsolete. This is very well defined by Miguel Ángel Hernández-Navarro in his book Materializing the Past, where he delves into the historical turn of art, theoretically revindicating the recycling of the obsolete in a process that operates in a direction opposite to that of the reification that the market exerts upon things. The obsolete technology that endures beyond its effective deactivation, having been relegated to the past, offers a functionality legitimized by its differentiation and its directness.

“It is only when the object no longer functions over the course of time that it reveals its true face. It could be said, in Lacanian terms, that at that moment the symbolic and imaginary layers are eliminated and the real appears. The fetish becomes a fossil, and the idea that the merchandise has a life of its own and has come out of nowhere is shattered, which is when the real forces that produced it appear. The myth vanishes and the dream disappears when the image of desire becomes ruin. Promises of happiness are then seen for what they really are: unfulfilled promises.” (Hernández-Navarro, 2015:125).

Thus, it makes sense to look within the specificities and difficulties of film material for a kind of revaluation of images. Working with film material requires practice and this is achieved by rehearsing, making mistakes and experimenting, all of which definitely takes time. Time in contact with the material, with the mechanisms and their procedures, makes it even less effective according to the logic of the market. The process of elaborating a filmic image implies an interruption of immediacy and in the temporary suspension between recording and viewing a distancing is created. Time and the unpredictability of the photochemical process impose themselves upon the regime of authorial possession and liberate them, at least partially, from projections and symbolism. “And the real appears,” says Hernández-Navarro, the image definitely appears.

Bibliography

Hernández-Navarro, M.Á. 2015. Materializar el pasado. El artista como historiador (benjaminiano) (Materialize the Past. The Artist as [Benjaminian] Historian). P. 125. Ed. Micromegas. Murcia.

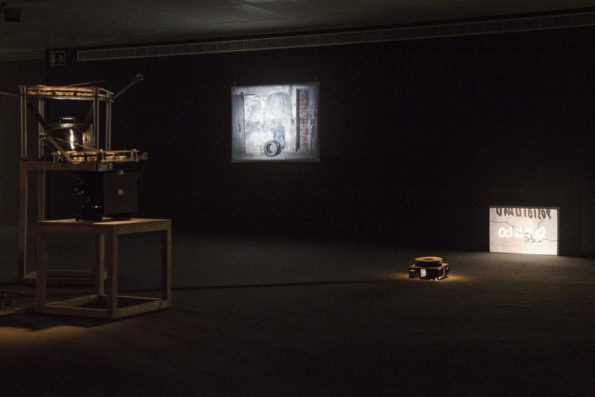

(Featured Image: I si veure era el foc, by Carlos Vásquez Méndez and Valentina Alvarado Matos, Sala de exposiciones de la Filmoteca de Catalunya. Photo: Juan de los Mares)

Carlos Vásquez Méndez is an artist, filmmaker and researcher. The media he uses are film, photography, performance, installation and sound. His works have been exhibited in several exhibitions and festivals. His film [Pewen]Araucaria (2016) received the Joris Ivens/CNAP award (Cinèma du Réel) and his film Las Cruces (2018) has won awards and recognition at festivals such as Yamagata, FIDMarseille and Mar del Plata.

His topics of interest are the relations between art and document, discourses on representations of the real and the role of the artist as a critical historian.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)