Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

CM: You may remember that during our pandemic connections I shared a talk by Mckenzie Wark, part of RIBOCA, “Ficting and Facting” [1] Wark, Mckenzie. “Ficting and Facting”. RIBOCA2, Public Programme 2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbInv9C1lY0 . I think the space that opens up between the concepts of cosmos and grammar is this relationship between “ficting” and “facting” that we talked about so much…

FB: These days I am focusing on my fiction writing, which happens to be – like the FICT project [2]Part of what originally catalysed our group was a call to think through alternate history issued by the Fragmentary Institute for Comparative Timelines (FICT – fict.site), which translated, for … Continue reading we started from – about alternate history. So, of course, it’s all about fictions and facts, and how these are similar active processes of articulation. In particular, I am dreaming up an alternate history in which the revolutions in scientific thought and technology that took place in Hellenistic times (after the death of Alexander the Great and before the formation of the Roman Empire) didn’t get lost. The historical importance of this period is only recently being rediscovered – first and foremost by Lucio Russo [3] Russo, Lucio. “The Forgotten Revolution: How Science Was Born in 300 BC and Why it Had to Be Reborn”. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004.. For this historian of ancient science something that was crucial in the innovations of this period had to do with the emergence of linguistic conventionalism: the idea that associations between terms and their meanings are not necessary and natural, but can be established arbitrarily (like the anatomical structures described by Herophilos and Erasistratus). This realization also made space for a relativization of systems of meaning, and it is not surprising that such conceptual instruments emerged in the time of formation of an ancient cosmo-politics – not in the propagandistic version that saw the greeks at the top, but in the truly novel syncretistic, diasporic, transnational and transethnic sense of a world (or an ekumen, at least) that got closer together. In this sense, the notion of cosmo-grammatics made me think also of this: of how, you know, really this kind of cosmopolitics brings with it a need to simultaneously kind of focus on the grammar, but also kind of unhinge from its dreams of stability and continuity to instead infuse change into it. This creates a gap between language and meaning, a gap that lets through both facts and fictions.

CM: It’s difficult for me to imagine how life forms can have a name embedded as well, maybe onomatopoeic or something like that…

FB: I can imagine it through my experience of living in a part of the world that does not speak my native tongue. And getting by through a language that I don’t approach so much grammatically, but pragmatically, through speech – which gives me even more of a distance from any naturalization. For example, in Italian most words are gendered; but English allows this difference, this distance from the expectation in Italian that everything will have a gender. And this already, you know, even in a very non-conscious way, still positions you in a different experience. You know, it creates the possibility of seeing past this naturalized view of language in some ways. And this is especially fascinating to me if we imagine an alternate scientific knowledge that remembers its epistemological grounding in this non-natural language. (…) You know, I do see how in my own way of being before opening up to really different languages, also more deeply, I also had a different disposition towards myself, let’s say. So this transformation also of the self that comes with it, I find fascinating. You know, I do think, for instance, that we do sound very different when we speak different languages. And I think that these kinds of things that we often too easily gloss over as translation issues are in fact deeper; they have this side of the relation in a way between a grammar or a language and lived reality, kind of almost ontological reality.

CG: Recognising the development of scientific language as arbitrary and conventional is a very refreshing thought, reminding me of Barad’s cuts [4]Barad, Karen. “Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning”. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007. It is an invitation to dismantle the entrenched naturalisation of scientific language – its terms, concepts, metaphors – as a stable mirror of reality. Considering a linguistic ‘system’ as a shared convention that serves to do things with the world, not just to represent and govern it, brings us closer to its openness. Precisely because it is used in the world, language is changed by it, by the relations in which it is used and those it creates. And it is not a matter of abstract relations that occur between purely cognitive and thinking beings, but of relations between bodies and materiality, immateriality, environments…

CM: Also learning different languages makes you more conscious about the playfulness of the language because you know that you don’t speak properly, whatever that means. And this idea that you don’t have the absolute control of a language puts you in a position to play with words. And I think this playfulness is very important.

SR: What you just said, Filippo, about how we change in which kind of language we speak, it makes me think of the notion of dreaming as well as collective imagination. Living in multi-language worlds, dreaming in different languages of different things in different ways, creates different realities for me. Another thought I have is to rethink Marija Gimbutas’s work on “The Language of the Goddess” [5] Gimbutas, Marija. “The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization”, Harper & Row Publishers, San Francisco, 1989 through this perspective of cosmogrammatics while bringing the language of more-than-humans, so, both animal, plant but also the animistic and spiritual world into this concept. What are the possible conversations in different kinds of assemblies? And this question of aliveness I see as the abundance and diversity of not only languages, but also cosmologies and worldviews. And in that sense, cosmosgrammatics are very necessary to have aliveness and life.

SN: I agree, Sina. This in mind, language is not merely a cultural tool, but some biocultural dynamics which in itself keeps shaping its relations, it is world building so to speak. And in this dynamic lies a big potential, some empowerment: if we modify our words and languages we can mobilise new or reactivate old knowledges. In my early practice I changed words and meanings not by intention, but by not knowing the English language very well. Sometimes I ended up trying to find a translation for something that could be expressed in one language but not in the other. And I got stuck, had to find more poetic rather than literal translations, which kind of created openings or portals to different ways of expression. And at some point this became a consciously chosen method. With my background in linguistics, this then often brought me to look at the roots of a word, and to trace the transformation of their meanings over periods of time, influenced by beliefs, politics, and technologies. Unearthing and acknowledging their roots made me consider a word as a plant themselves. Returning to these roots, is again like another portal to alternate worlds; worlds in which these words formed and themselves were part of making relations. Through customisation to a specific way of using languages, and this happens mainly with the language that we grow up with, we tend to take it for granted, but then digging up these roots helps us to return to specific relations, and potentially our own roots. Further there is a very anthropocentric conception of language which reduces an imagination of alternate forms of communication with other beings. It narrows language down to sounds and speech, while communication and language could be wordless, but rich in expressions of bodies, smells, movements. For me, when we talk about cosmogrammatics, I think of the many potential languages, gestures, words, sounds, as portals to open, to shift between worlds both by creating similarity or by inviting ambiguity also as well, by creating not binary juxtapositions but rather multiplicity within one poetic expression.

CG: This makes me think of our Fracto experiment (1), when we started to imagine how the characters participating in the transplanetary conference could develop a shared methodology to explore the messages they received in their timeline. We asked ourselves “how come they all knew how to participate in the conference while living in worlds where subjects, objects, pressing issues, technologies and histories are different? How did they find each other?”. So words as portals sound promising to me!

AC: What Filippo said about the situatedness of language made me wonder about what people are afraid of, or defending from, when they get angry about neologisms or grammar mistakes. It’s something that triggers some people so much. I wonder what’s at stake there. I also had to think about our name as a collective, Fictopus. Part of it came from a difficult situation: We were having issues with the FICT (2) project, and didn’t know how to proceed with it. We later decided to keep that negative component, that was ultimately also a founding moment, in the name, but we added the octopus and merged the two words. A bit like Paul B. Preciado kept the B. from their previous name, as Connie told us a long time ago.

SN: Yes, this was a moment of healing the group, in the sense of ‘making it whole again’. After the group had shrunk due to the project’s challenges we returned to our initial constellation, the cosmos as you name it, Connie. Becoming something new while returning to our initial formation, adding ‘Octopus’ to ‘FICT’ was a good way to both remember and transform experiences through naming.

AC: That’s true. I’m now thinking about a book I mentioned during our early days, “La Grammatica della Fantasia ” by Gianni Rodari [6]Rodari, Gianni. “La Grammatica della Fantasia”. Introduzione all’arte di inventare storie, Einaudi Ragazzi Ed. 2011, the internationally known Italian author of children’s books. I recently found by chance a German translation of the book. It’s the only theoretical book he published, about inventing stories. Reading it is a bit like going behind the scenes of his methods and techniques: He played a lot with language, and the book is ultimately about the liberating potential of words. Again, I’m wondering what it means to choose a word, or to modify a word, to play with it. Rodari also made a book called “Il Libro degli Errori” [7] Rodari, Gianni, “Il libro degli Errori”, Einaudi Ragazzi Ed., 2011 , the book of mistakes, with stories built around spelling errors and word puns. His work found inspiration and references in milestones of modern art and poetry like Novalis and French surrealism. I’d like to work more on that with you one day. The fact and ficting and the non-linear storytelling threads that emerged from our conversations are very important to me, and informed my research and projects ever since. I’m very happy to talk about it with you again. [8] To continue reading the conversation visit Fictopus hotglue: https://berlinrogue.hotglue.me/?A-Desk%20Conversation

NOTES

[Featured Image: textiles2020_thread Sybille Neumeyer Design©formphase]

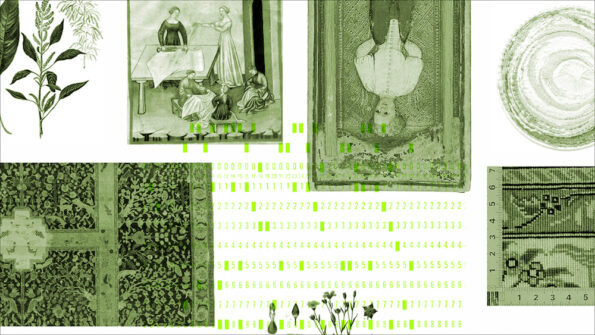

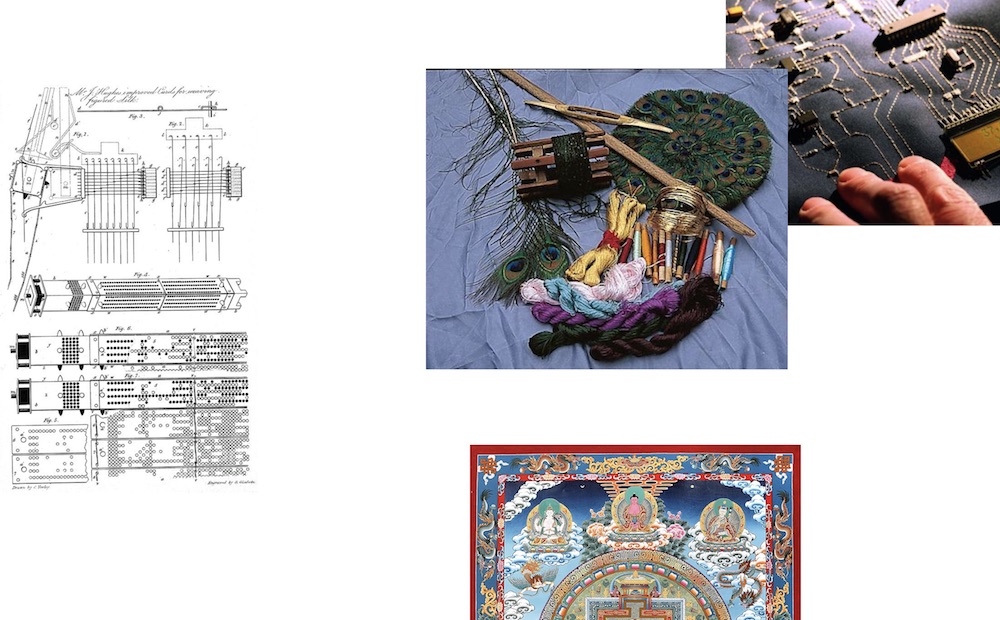

All images are screenshots from Fictopus’ project “textîles – threading speculative archipelagoes” : https://berlinrogue.hotglue.me

Inspired by Ursula Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, textîles gathers non-hero stories, stitching “footnotes” back into historiographic fabrics as a method for collective memory-making. Meant as a way to unweave and reweave the relational knots of multiple events, time- and landscapes, the project pays attention to the response-ability inherent to the work of threading stories. Choosing the threads is a powerful matter indeed.

| ↑1 | Wark, Mckenzie. “Ficting and Facting”. RIBOCA2, Public Programme 2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbInv9C1lY0 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Part of what originally catalysed our group was a call to think through alternate history issued by the Fragmentary Institute for Comparative Timelines (FICT – fict.site), which translated, for us, into an event as part of Fracto, where we unravelled some alternate histories of transhuman becomings by pulling on different textile threads: https://www.occultomagazine.com/textiles-at-fracto-2021/ |

| ↑3 | Russo, Lucio. “The Forgotten Revolution: How Science Was Born in 300 BC and Why it Had to Be Reborn”. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004. |

| ↑4 | Barad, Karen. “Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning”. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007 |

| ↑5 | Gimbutas, Marija. “The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization”, Harper & Row Publishers, San Francisco, 1989 |

| ↑6 | Rodari, Gianni. “La Grammatica della Fantasia”. Introduzione all’arte di inventare storie, Einaudi Ragazzi Ed. 2011 |

| ↑7 | Rodari, Gianni, “Il libro degli Errori”, Einaudi Ragazzi Ed., 2011 |

| ↑8 | To continue reading the conversation visit Fictopus hotglue: https://berlinrogue.hotglue.me/?A-Desk%20Conversation |

Fictopus is a multidisciplinary research collective, its members weaving their respective practices of non-linear, multiperspective and speculative storytelling. They bring together the independent but connective thinking of the arms of an octopus, centered around questions of ficting and facting, modes of learning and unlearning, and more than human worlding.

Fictopus are Filippo Bertoni, Alice Cannavà, Chiara Garbellotto, Constanza Mendoza, Sybille Neumeyer und Sina Ribak.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)