Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Fanon said that “decolonization will be a violent process,” and he had plenty of reasons to be convinced of this.

In Bolivia, between 2000 and 2003, there were strong anti-colonial revolts, such as The Gas War and the Water War. These mobilizations represent for many Bolivians a radical breakthrough with respect to the colonial order and all of its current relationships to multinationals, the white/mixed race local oppressor class and the government, co-opted by the mandates of globalization and its processes of armed looting and other types of violence against Bolivian bodies and territories. After this process of resistance and the expulsion of the plundering companies and their servile politicians, Bolivia remaines an indigenous territory struggling with deep colonial wounds. These revolts meant rediscovering our capacity for resistance through popular organization, community power, and the persistent ancestral anti-colonial force that gave rise to a multi-ethnic country, which was and is a process of reparation that resulted from popular power, the taking from the hands of settler thieves what belongs to us.

I am writing this from my own personal archive, having been there, and also with the permanent need to find genealogical references from the past that can motivate us to continue fighting despite the cooling and the supposed impossibility of changing everything in this anti-women world. To remove the settlers from our territories was possible, but will removing the settlers from the museums also be possible? How does restitution or reparation operate, proposed as it is from the heights of colonial privileges and its ally, the avant-garde? Is it possible to decolonize museums?

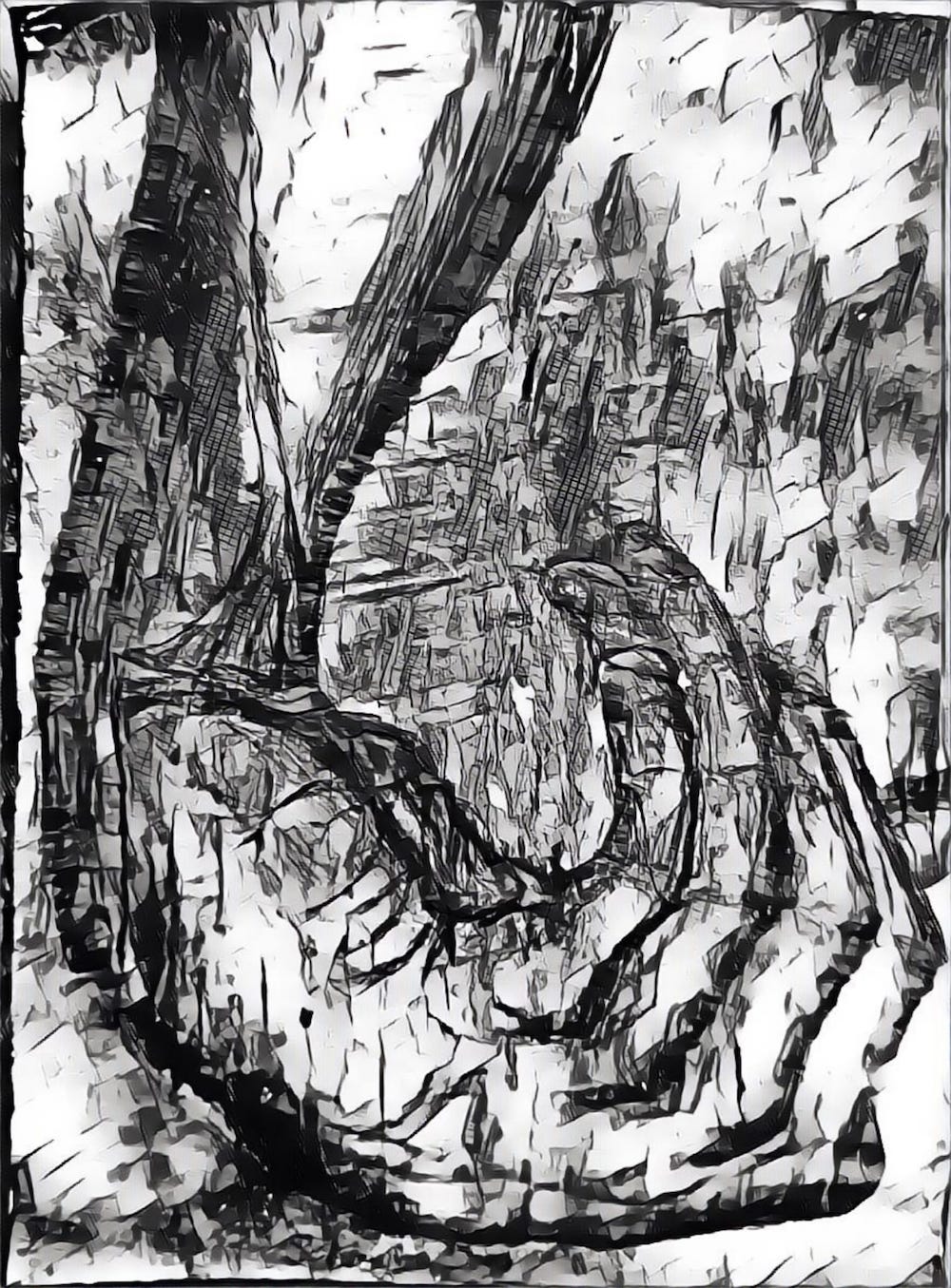

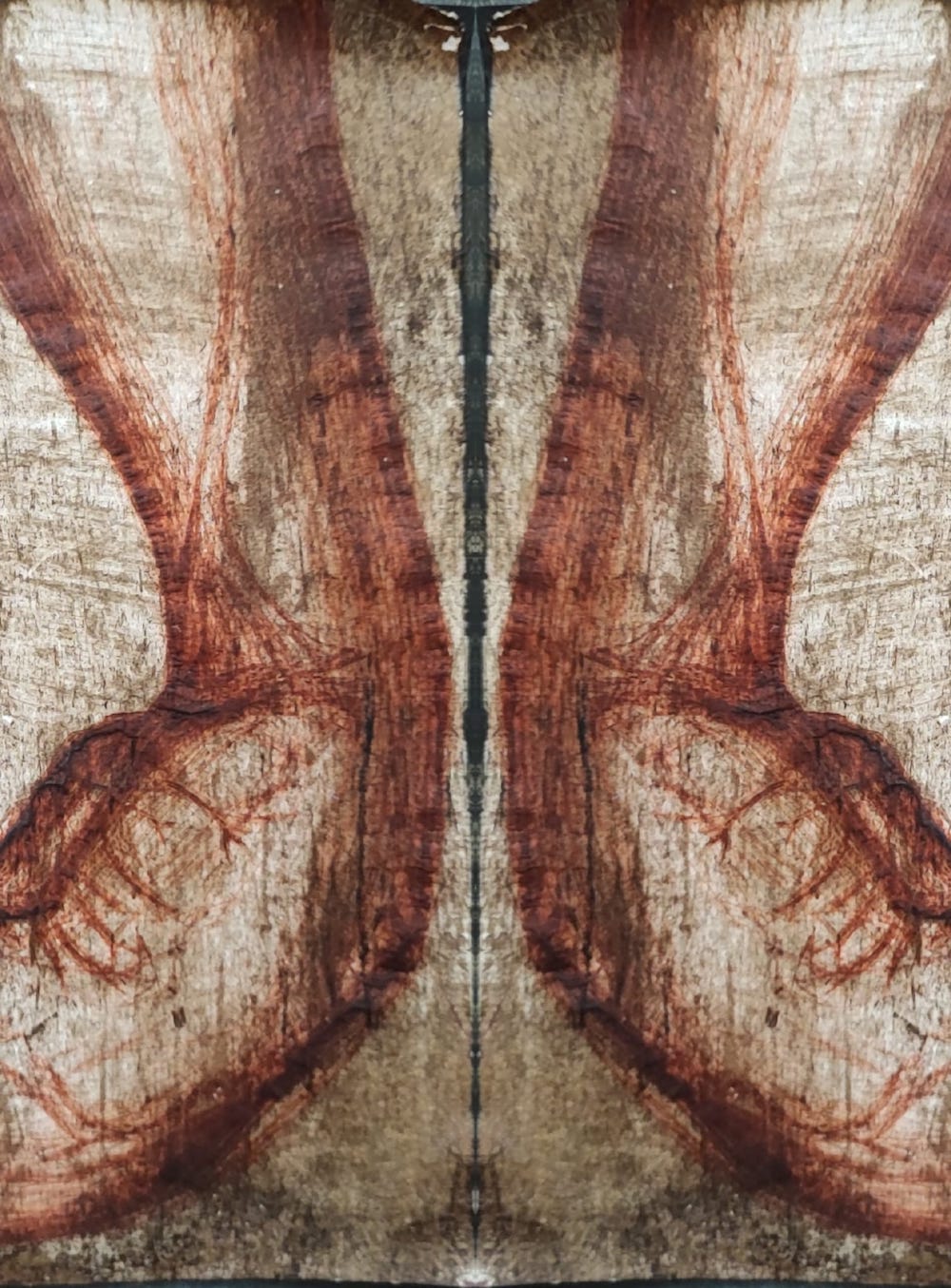

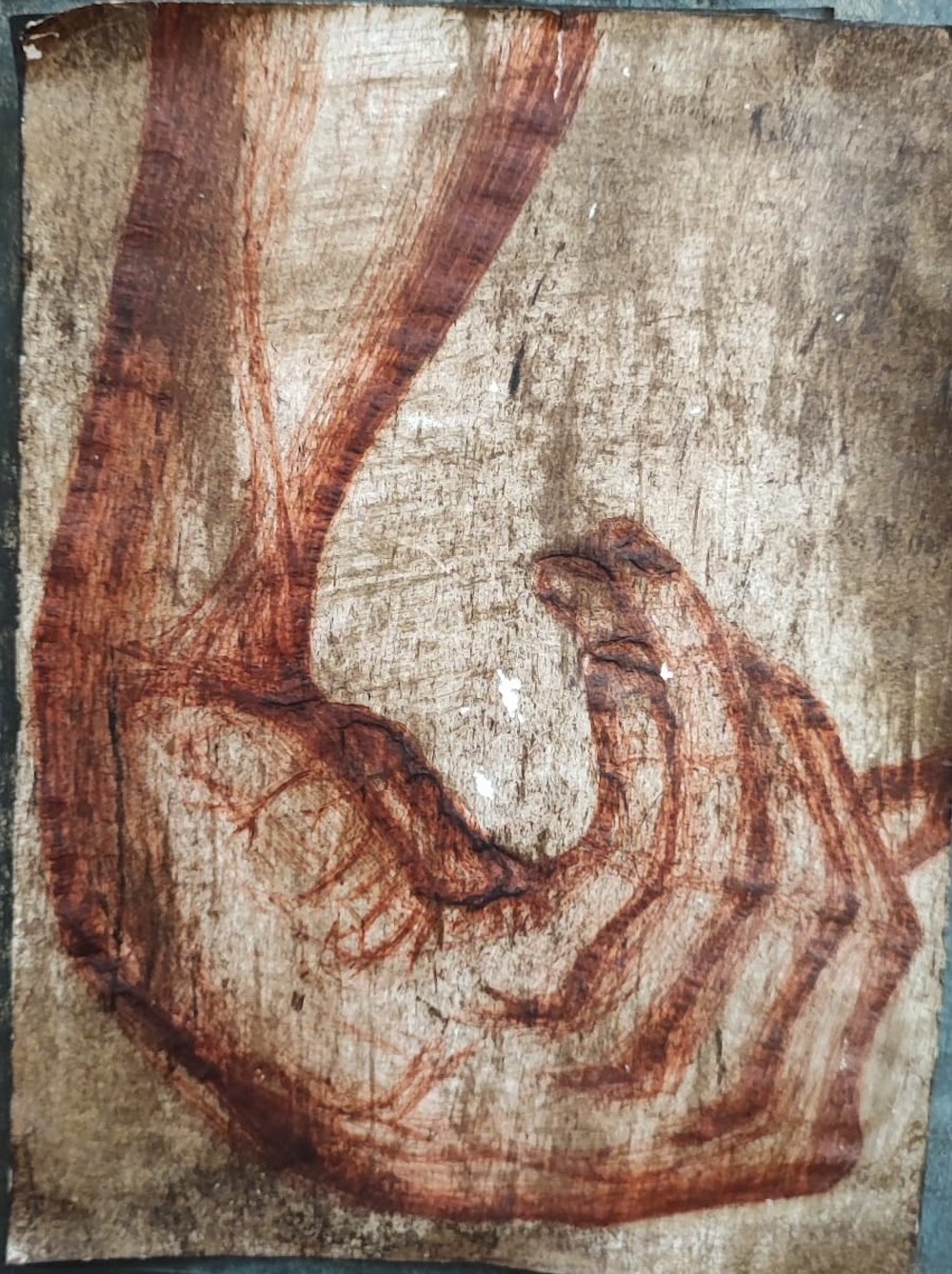

Drawings by Hache Mau. Ballpoint pen on paper (2000)

For years now, some museums in Spain have begun a process of “debate and actions” on a proposal for supposed decolonization based on restitution, reparation and return, although the guarantee of non-repetition is almost never mentioned. At the same time, narratives and the viralization of denialist/nationalist positions of colonial violence towards our territories in the global south are socially generated, denying the genocides of our people. This gets called, in a racist way, “Black History” or imperial-phobia.

Starting from a reflection by Yki Yos Piña, a black transvestite activist, about how “colonial theft activates a historical wound,” we can reflect on the permanent cruelty of the transtemporal process with which colonial violence has marked our bodies in regards to the denialist and trivializing debate about the whiteness that exists not only in academic and political circles but also deeply within local social circles. Supremacism is established in citizenship by granting it the privileges of the inherited colonial order. The insistent and cynical debate that is also generated about return (yes or no) is quite violent and reveals the place of power regarding our spiritual, historical wounds. Activists in our broad spectrum are permanently violated by the good students of colonial pedagogy, as there are no exceptions, there are masters everywhere, even benevolent ones.

Coloniality and its racism, coloniality and its plundering, coloniality and its patriarchy, coloniality and its genocides still exist, just look at all the violence against the Palestinian people and their bodies and their extermination transmitted online. As non-white racialized bodies, migrants can speak from their wounds, their own and collective wounds, which are never separate.

We inhabit a world of borders, composed of scars and wounds on the land and in our bodies that mark the spot where the looting begins, scars in our beliefs, in our identities, in our worldviews. Western museums owe us all much more due to interest. Where there is a wound, there is a debt.

The politics of forgiveness have such a sinister history because they are the history of colonialism itself and thus constitute the moral supremacism of the white settlers, their descendants, their companies, and their governments. We must be aware of this and we must radically distrust any structure that represents both symbolic and material legitimation of the historical racial hierarchy and all its economic equations. Distrust all white people in situations of power, distrust everyone.

Regarding colonial order, we cannot avoid thinking about the distribution of “the human” and “the non-human” from every organization in terms of the privilege of destroying or saving “the other” in order to refer to oneself at the top of the order. In this sense, the museum has also historically been a factory that reproduces Euro-centered white humanism, sublimely and cynically based on the plundering of other peoples.

The distrust of the decolonization narrative comes from the idea that all reparation must go far beyond the symbolic and dialectical in order to take into account the capacity that capitalism has of appropriating and profiting from the many political demands to sustain its narrative of modernity, inclusion, diversity, universalism, and assimilationist processes such as that of liberal feminism, or LGTBIQ and its nationalist discourses (feminacionnationalism, homonationalisms). These are tools of “salvationist” propaganda used by genocidal settlers in territories where geopolitics exterminates the indigenous people for a territory of strategic location and plunder that guarantees their zone of privileges.

We need a radical and transformative approach that understands that the structures that plundered objects of cultural representation from territories dominated by colonialism have been used as a business-like economic exercise that has served and serves to configure the world system and all its supremacist practices, used as tools/trophies/fetishes to create pedagogies and distances between the civilized and the savage, between the European sublime human and the non-European protohuman.

We understand restitution as important though not sufficient to challenge the world system that continues to operate with extractivist, genocidal and dehumanizing logic. As Susy Shock, a black Argentine transvestite activist, says, “We don’t want to be this humanity anymore.” A return does not speak enough in real terms of the theft, looting and all the violence that involved both the objects and subjects used in their museums to determine their absolute supremacist ownership.

We recognize that these current actions, including historic reparations, are designed to sustain the system. To truly decolonize, the museum must disappear. As Mikaela Drullar, Dominican trans activist, says (paraphrasing), “The museum cannot be decolonized, because the museum is the colonial structure itself, just as the States cannot be decolonized.”

Drawings by Hache Mau. Ballpoint pen on paper (2000)

If we agree to embrace returns, restitutions, racial quotas (sarcasm), we embrace the possibility that the communities that have survived all this violence for more than 500 years can reunite with their sacred objects/subjects, thinking about other denied ontologies that still resist. We understand that from Western logic it is impossible for them to treat these “objects” as entities, sacred living subjects, to respect their spiritual and genealogical importance and their multiple cultural meanings, not just as simple museum pieces to be returned, even if the narrative of social justice accompanies them.

The role of communities should be fundamental in these processes but it is not.

Can museums thus transform themselves and stop reproducing the power structures that gave rise to them? We can imagine several politically-related issues, so as that museums should be transformed into spaces of activism with real protagonists where there are radical critical reflections on the historical processes of epistemic, material and symbolic plunder that challenge every Western supremacist structure and canon, in order to promote places of the activation of collective memory and reparation, freeing up budgets. This would imply supporting political causes of resistance to current colonial processes, financing academic and non-academic research, in the Western sense of the academy, of anti-racist activism, denaturalizing supremacist places of power, academies, universities, museums and all other such sites. Can that happen?

When will these reflections and other anti-racist ideas be heard in a space as deeply racist as Catalonia? When will there be a debate on the recognition and reparation of the process of trafficking in African people for the colonial regimes in the Americas. The damage is as immense as the enrichment and hypocrisy in this city.

We propose challenges that we know are impossible to carry out alongside the maintenance of the political, economic and moral structure and practices of whiteness and the colonial institutions that sustain its privileges. We also question benevolence from historical places of production and reproduction of “neo” colonial and capitalist values. Will they be accepted?

Drawings by Hache Mau. Ballpoint pen on paper (2000)

HACHE MAU is a marron activist, anti-colonial migrant sex-gender dissident born in the colonized territory now called Bolivia, was part of Red de Cuidados Antirracista in the process of pandemic 2020, she was also part of other anti-racist political resistance collectives in Barcelona. Her activism focuses on challenging structural racism, sexual binarism and all hegemony from a migrant indigenous-descendant marikatravesti perspective. She was part of the coordination of the anti-colonial trans cycle in Barcelona in 2023.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)