Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

A conversation with Santiago Villanueva (Azul, Buenos Aires, 1990) on the illusions of recent art, not so recent Argentinean history and some of his own works of the past ten years.

Claudio Iglesias: Let’s begin with your obsession with provincial museums. I remember the project entitled Adquisición (2011) that you presented for the BA-Petrobrás Visual Arts Award and that consisted in purchasing a work by a little known artist – Anselmo Piccoli – with the money of the art award to donate it to the Contemporary Art Museum in Azul. In 2011, the fantasy of these local museums and forgotten works that could be purchased today for very little seemed new, particularly in an environment that showed such fascination with originality and with everything that smelt global, like the Buenos Aires art scene of the time, still governed by the ideas of the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Santiago Villanueva: In those days I was trying to combine the experience of the avant-garde trends of the sixties rediscovered at the beginning of the century, with their idea of internationalism, etc., and the classless and invisible artistic heritage of our art history. Adquisición tried to combine a ‘dematerialised’ strategy that we might associate with Conceptualism (working with an existing artwork instead of producing a new object), with a more heat-resistant material from our local tradition. My works of that period are quite sharp, ironic: the methods of their production, on the one hand, and the material I was using, on the other. If I think of other works in which local history triggered research instead of ironic comment I see that all that gradually disappeared, but in 2011 I felt there was strong opposition to the art of the previous decade with its globalist intentions.

CI: That same year you joined La Ene [Nuevo Museo Energía de Arte Contemporáneo, an institutional space set up by Gala Berger and Marina Reyes Franco in 2010].

SV: La Ene was inspired to a great extent by the art scene of the first decade of the century, especially by its direct relationship with institutional projects run by artists like Trama and Duplus: the idea of creating a new institutionalism, of working in management, seeing what was lacking, etc. These projects tried to make up for an absence (that of a contemporary art museum in Buenos Aires, in the case of La Ene) and confirm something we’ve always said: that what characterises the new century is the idea of projects, not works but projects. In fact, at La Ene we work with site-specific artists’ projects — exhibition projects, artists’ residencies, talks, etc. There was something heroic about it, as if we were saying ‘Look, here we are, building from a situation of precariousness something that’s lacking: neither the state nor the wealthy are doing it, we’re doing it’, etc.

CI: Speaking of the generation of 2000, an artist I know put it this way: ‘We were tired of the post-dictatorship, tired of so much drama: AIDS, the missing, this and that; we wanted to be artists, that’s all, and we read Phaidon books, Gabriel Orozco, Thomas Hirschhorn … those were artists for us.’ Around that same time you mentioned art reviews published in Argentina during the thirties, but wasn’t the system similar, in its irony, to the strategic and less dramatic idea of the generation of 2000? Perhaps the evolution of artistic taste in Buenos Aires over recent years wasn’t related to the return to an invisible local tradition but to a new attitude that is no longer ironical, rather as if we said ‘Hey, let’s stop thinking that these artists are the outsiders of the canon and let’s start taking what they do seriously.’ From this position, without the blinkers of irony, in your latest shows we’ve seen things that have only recently appeared under the spotlight, to be specific a new place for small objects as the format preferred by younger generations related to the world of discos and to the local Surrealist network. The fact that an artist of the post-Internet generation like Emilio Bianchic and an admired Surrealist of the mid-twentieth century like Mariette Lydis could be displayed in the same show (Borderland, 2016, CC Recoleta) is symptomatic of this.

SV: I was thinking of the idea that appeared in the nineties of working with waste from a position of adoration, but not the waste of the art informel of the fifties that carried on degrading waste, mistreating it even. In the nineties, waste was relocated more tenderly, and although my first works, as you say, were colder, there was also empathy with those materials. There was a transition from that moment to a greater involvement, and instead of manipulating objects it became necessary to explore them, present them, make them into books, etc.

CI: I’m now thinking of Alejandro Cesarco and his reappropriations that are also very tender (sending flowers to the female artists f the generation of 1970, for instance).

SV: Cesarco belongs to a generation that used more global codes, and the influence of Conceptualism is much stronger in these works. There’s an idea of correcting history, but in a way that integrates themes and their presentation in the tradition of Conceptual Art.

CI: We were speaking of the generation of 2000 and I was thinking that, to make it simple, I’d say that the utopia of that moment immediately following the crisis of 2001 was that artists produced non-profit projects. That’s what we talked about: professional work, the institutional development of art as an industry, etc. On the other hand, in the art world of the post-dictatorship that emerged in the decade of the eighties and continued well into the nineties, art focused on existential fragility and vulnerable ways of life (such as the homosexual community, for instance). I liked Alejo Ponce de León’s description of painting as the artist’s path towards professional assimilation as opposed to drawing, the ‘basement’ where political urgency and stark existence are at stake, an idea that also dates directly back to 1980 and yet portrays our present. Perhaps what alienated the generation of 2000 was the hope of moving from drawing to painting, from basement to surface, from fragility to professional assimilation.

SV: In the case of the generation of 2000, the previous habit of forming artistic groups was broken. The generation of 2000 consists of separate artists, each with their own specific interests. And there’s also middle-class art — drawing versus painting. As Ponce de León says, drawing is for the middle classes.

CI: Kerry Doran’s text for Artforum on the last arteBA biennial asserts this character of local collecting. More than Argentineans learning from global markets governed by the economic roulette, it is the markets that should be learning from a less unstable form of collecting, less ambitious and less developed but, as Doran says, more sustainable.

SV: These living-room collections are the ones that trigger the debate on art history. Big spending, works that can be purchased for a professional home, like a small-size Piccoli, 50 x 60 centimetres. That’s a middle-class format. These aren’t museum works, they’re living-room works.

CI: Let’s talk about what that living-room work provokes when it’s shown in an exhibition some fifty or sixty years later. Wasn’t there something similar in your 2016 Surrealist show at Isla Flotante?

SV: That’s when I began to work with formats that were less clear-cut, although I still intended to shift something around in art history, as if it were a piece of home furniture. Particularly with the idea of analysing Peronism in art from a new standpoint, looking back at Argentinean art of the mid-twentieth century. I wanted to bring domestic Surrealism back, the Orión group that emerged in 1939 to be precise, that was quite backwards in comparison with French Surrealism and declared that if Surrealism didn’t reach Buenos Aires the results could be catastrophic. Being avant-garde no longer means advancing but avoiding a greater tragedy. Catalogue essays also made reference to the way in which Peronism had used Surrealism in an indirect and almost paradoxical way with works purchased at Mercadolibre.com, confirming that exhibitions that are useful to art history can be organised without institutional work and the endless bureaucracy of loans, etc.

CI: Speaking of bureaucracy, let’s move on to 2019, the art space you opened this year with Fernanda Laguna and Rosario Zorraquín, a space that is characteristic of today’s context.

SV: 2019 is an art space in a corridor that gives on to a courtyard in a building of artists’ workshops and that is supposed to last one year. There’s something fictional about it, posture or imposture even, that on the one hand is more characteristic of the nineties and, on the other, has a lot to do with what you were saying before, what’s taking place in Buenos Aires right now — a new presence of works in reduced formats (drawing unlike painting, as Ponce de León says), something that had no planning, no funding, no bureaucracy. We have shows staged again in houses, in offices, in improvised spaces. 2019 was that sort of place and it also intended to look outside of art and organise shows by artists with no previous career. The next show is a solo exhibition dedicated to Gladys Afamado, a Uruguayan artist who is almost a hundred years old.

CI: I’m thinking of the ‘project artist’ as a characteristic figure of the 2000 generation who presents his work at La Ene shows, as opposed to the Matías Tomas exhibition you hosted last year at the Flux bar, a bizarre basement in Retiro. Almost without realising it, we move from the project artist to the artist who shows his work in a bar, which is something we hadn’t seen since 1988 at least. Is this a sort of new lumpenisation of art? Or, to use the term employed by Marlie Mul and Harry Burke, a process of deinstitutionalisation linked to the category of survival, to the reflex of becoming entrenched in existence (very typical of the eighties in Argentina)? There are two titles I find meaningful: an artist like Ilse Fuskova and the Cuadernos de existencia lesbiana that she edited and published right after the dictatorship, and two figures of the literary avant-garde like I Acevedo and Paula Peyseré with an essay on the political situation entitled ‘Queremos avisarles a todxs que seguimos vivxs’ which I consider a modern classic on account of its return to approaches of resistance (from gender dissidence, salvageable from other angles too). All this while mainstream institutions were coming up with excuses like ‘fear of the revival of fascism’ to withdraw into conservative positions (like something that a cynic might discover at this year’s Venice Biennale?). It’s strange now for us to think back to a project like La Ene, with its far-fetched radical ideas: ‘We’ll show civil servants how to set up a contemporary art museum with a couple of benches in just three square metres’. Were these ideas also valid when the institutional ecosystem was more promising?

SV: For me the idea of deinstitutionalisation makes sense as a sort ofdetox and has to do with the local political issue of the Kirchner cycle that came to an end in 2015 and the faith we had then in our institutions, non-profit projects, etc., all that you were saying about returning to institutions and working from within them. And now, disappointed, we are detoxing ourselves from the disease of institutions. Sergio Avello and his shows of the nineties in toilets at railway stations are an example for 2019 because they had no programme. Rather than think of a space just for a year we want a space purposely for a year to see what we can do in a year.

CI: Days gained, as Carlos Giambiagi would say, ‘I’m not sure about anything, but every day I spend working will be a day gained.’

SV: I like [the sound of] days gained: we have no hope, no money, no grants, no future, so let’s just think of what we need. Right now.

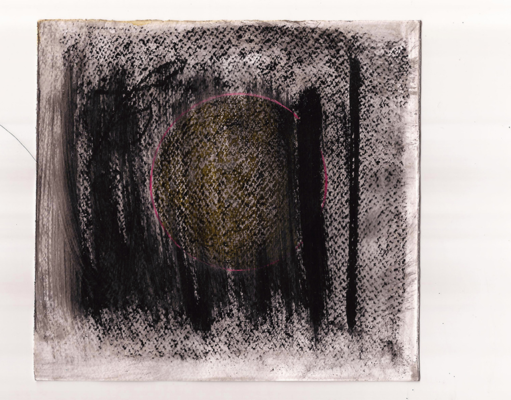

Images of the exhibition by Matías Tomas at Flux

(Highlighted image: work by Matías Tomas)

Claudio Iglesias is an art critic based in Buenos Aires. His latest books are Corazón y realidad (Consonni, Bilbao, 2018) and Genios pobres (Mansalva, Buenos Aires, 2018).

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)