Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

… or maybe there is. Because a certain contradiction exists between thinking and writing about obsolescence and ruin with a well-constructed text: one comprising an introduction, development, and conclusion. As if it were a building (as Proust said with his textual cathedral), wanting to construct a text in order to talk about two notions invoking precisely deconstruction could seem insensitive (or lacking “rigour”, maybe, lacking in language politics, perhaps): ruin and obsolescence invoke, indeed, the deconstruction of something regarded both as a spatial whole and a temporal whole. A building, a commodity, or any other entity, even a text as a whole of meaning, spatial and temporal. A whole as a unit, as a presence.

… sometimes, always. Maybe, too, in what Blanchot said when he wrote that there must exist some complicity between a text and what it talks about, beyond content. Or, to use terms I have been working on for years: the way something is said means more than what is said. The how of a text is therefore a component of more importance in the politics of meaning than shared content itself. Rancière writes: “what we have ultimately proven is that a theory’s political effect depends less on its phrasing than the position it adopts in enunciation”. And, thus, a theory of writing perfectly appropriate for this text on ruin and obsolescence: “in the same way the proletarian becomes split into himself and into a bourgeois, in which the plebeian becomes split into himself and a patrician, a split takes place there too, within the language. A split takes place, on the one hand, in theory, content, and on the other hand, in praxis, in ways of enunciation: the how of writing becomes split in itself and the ‘what’ to interrupt that non-equality of meaning in the textual community. Language praxis would say, then, to theory: “I, like you (I count too in what the text accounts for, I am also capable of meaning, I, too am capable of politics, etc)”[1] First, Jacques Rancière; then, myself. See Jacques Rancière and Javier Bassas, El litigio de las palabras. Diálogo sobre la política del lenguaje, NED Ediciones, Barcelona, 2019, p. 12 and 13.. As if, out of ruin and obsolescence, it were only possible to construct a text from ruin and obsolescence: without an effective whole, fragmented, suspending its causa finalis.

… just as there are materials in here (notes, quotations, reflections) but there is no text if we take that unit of meaning that is introduced, developed, and concluded as “text”. There is no “text” here according to that sense. There are other senses, such as the one collecting the echo of other voices, because an echo is, also, the ruin of voice. Just as our voice speaks of ruin and obsolescence, reprising the echo of other voices: here, in a here deconstructed in thought and writing, nothing begins and nothing is to be constructed for any given end. Reprising Foucault: “I wish I could have slipped surreptitiously into this discourse which I must present today, and into the ones I shall have to give here, perhaps for many years to come, I should have preferred to be enveloped by speech and carried away well beyond all possible beginnings, rather than have to begin it myself. I should have preferred to become aware that a nameless voice was needed to join in, to continue the sentence it had started and lodge myself, without really being noticed, in its interstices, as if it had signalled my pausing, for an instant, in suspense. Thus there would be no beginning, and instead of being the one from which discourse proceeded, I should be at the mercy of its chance unfolding, a slender gap, the point of its possible disappearance.”[2]Michel Foucault, L’ordre du discours, Gallimard, París, 1971, pág. 7-9. Reprising here Alberto González’s translation into Spanish, El orden del discurso, Tusquests eds., Buenos Aires, 1992. … Continue reading.

Reprising and displacing Foucault. Because of my lack of a beginning, of my ruin of an obsolete text, the echo of a voice being strung together here is not a result of the order of discourse, developed in this quotation by Foucault. The lack of a beginning is a result of the disorder of discourse, indeterminacy containing the politics of ruin and obsolescence.

…and before my voice, Derrida’s voice was also there: “It’s like a ruin which doesn’t come after a piece of work but which is produced, from the origin, by the advent and structure of the work. In its origin, there was ruin. Ruin extends to the origin, that’s what came first, in the origin. Without a promise of recovery” [3]Jacques Derrida, Mémoires d’aveugle. L’autoportrait et autres ruines, Éds. de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, París, 1990, pág. 69. I have translated Derrida the only way he can be … Continue reading. The politics of ruin is the ruin of origin, of presence, of subjectivity. The ruin of any text which talks about ruin.

(…)

… in order to concur with this art against the grain by Miguel A. Hernández, because we are among the ruins of Modernity. I would also say that Postmodernity is something like obsolete Modernity. But this is our joy because “it is in spoils, in catastrophe, in the fossil of a fetish, in the ruin of dreams where Benjamin finds the energies which are necessary for revolution. In these “spoils of history”, Benjamin notices real potential. With the obsolescence of objects, with the revelation of its hidden face, we could say that dreams are also “distilled”. In some way, dreams, promises, seeing themselves as a failure, are clearly identified. And in this way, it is clearly ascertained that there are still dreams and promises. That is to say, that history is still open. When we see their destruction is when their potency is revealed”.[4]Miguel Ángel Hernández, El arte a contratiempo. Historia, obsolescencia, estéticas migratorias, ed. Akal, Madrid, 2020, pág. 56. A capital book for understanding contemporary art from the point … Continue reading

There is only potency there in the time we are living in, in art-literature-philosophy-politics-etc: signalling the politics of ruin and obsolescence oils recovering lost time, rewriting History in such a way that it remains open and, thus, in the indeterminacy of meaning…

… because “the reference to the critique of progress by Benjamin […] has become a cliche in contemporary art history, which keeps this attitude of rescuing the obsolete and outmoded as a critical position. However, […] changes in production politics and the reinforcement of the strategy of programmed obsolescence transform completely the critical meaning of the use of the past, which has now become integrated within the logic of consumerism. […] The point would be to find ways to avoid integration or, at least, when one becomes aware of its perils, identifying them, battling them, instituting critical distance, avoiding, by all means, to be blinded by nostalgia. [5]Ibidem, págs. 44 y 49..

…even if not this way, because it wouldn’t be so much about “awareness”, or about “critical distance”. It would have more to do with living in an obsolete way (“Il faut être absolument obsolète”, Rimbaud would say today) with a ruined subjectivity, living like ruins and everything obsolete. It would have to do with suspending determinacy at all levels, dwelling in that oceanic circulation between what I am, my determinacies, and what I am not, the indeterminacy of ruin which is there in origin, like the endless stare at an obsolete object which talks to us from a different time …

Louise Ackermann writes….

Jeté par le hasard sur un vieux globe infime,

A l’abandon, perdu comme en un océan,

Je surnage un moment et flotte à fleur d’abîme,

Épave du néant.Thrown by chance to a dismal old globe

To oblivion, lost like at an ocean

I drift for a moment, then float,

A wreck of nothingness.

…that is what maybe Rancière’s in-between [6]”A process of subjectivation is thus a process of disidentification or declassification. Or to put it another way, a subject is an in-between, a between-two”, in J. Rancière, Aux bords … Continue reading referred to: the movement between determinacy and indeterminacy I am proposing, the praxis of emancipation and, also, political art when…

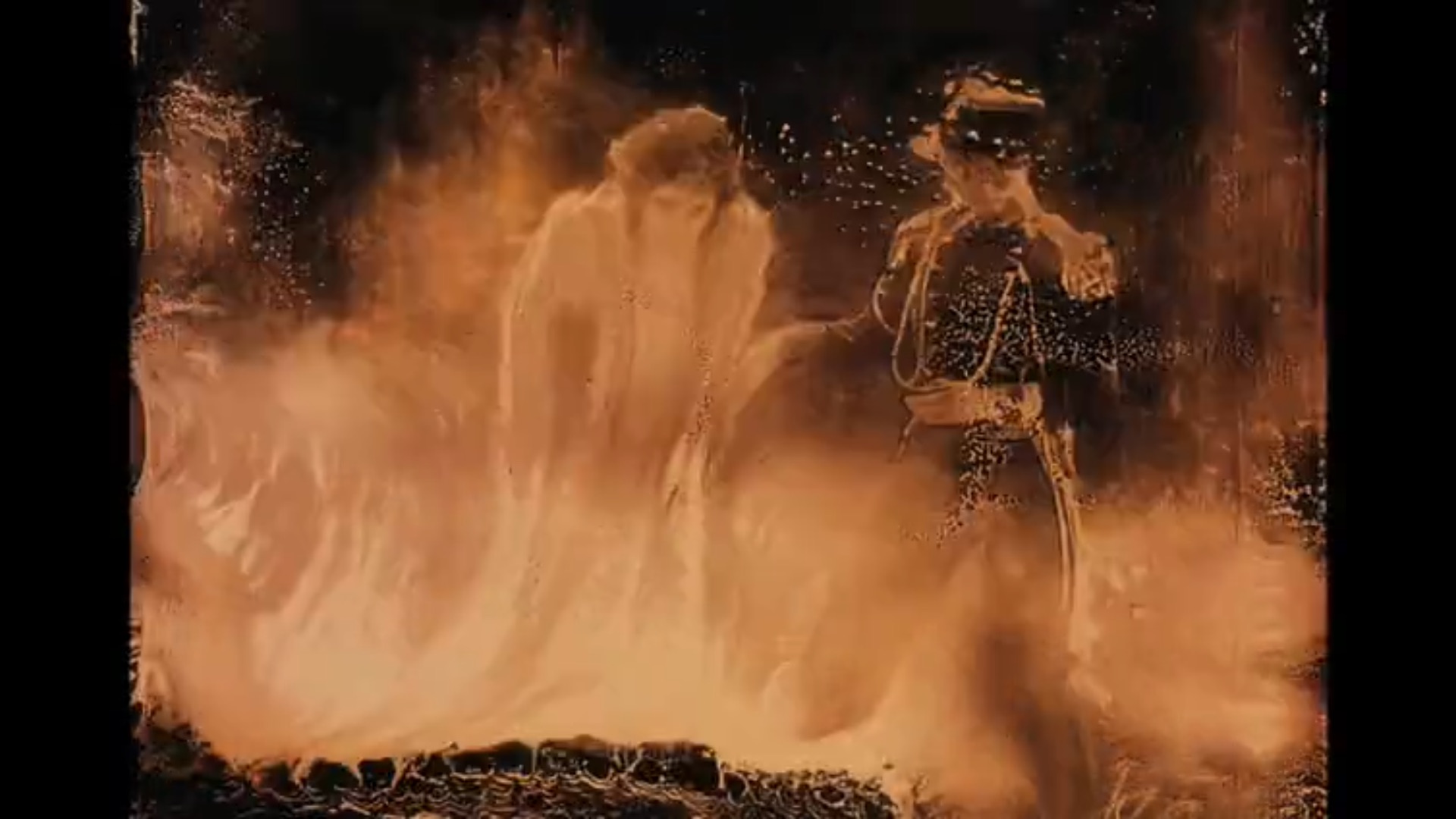

Ruina y obsolescencia de una película que muestran otros tiempos de la imagen. Fotograma de Light is calling (35mm, 8 min, 2004) de Bill Morrison.

(Imagen destacada: Fuego político: ruinas y obsolescencia de los contenedores urbanos).

| ↑1 | First, Jacques Rancière; then, myself. See Jacques Rancière and Javier Bassas, El litigio de las palabras. Diálogo sobre la política del lenguaje, NED Ediciones, Barcelona, 2019, p. 12 and 13. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Michel Foucault, L’ordre du discours, Gallimard, París, 1971, pág. 7-9. Reprising here Alberto González’s translation into Spanish, El orden del discurso, Tusquests eds., Buenos Aires, 1992. As a matter of fact, this book recreates Foucault’s opening lecture at the Collège de France, given on the 2nd of December of 1970. |

| ↑3 | Jacques Derrida, Mémoires d’aveugle. L’autoportrait et autres ruines, Éds. de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, París, 1990, pág. 69. I have translated Derrida the only way he can be translated, ruining the original: “C’est comme une ruine qui ne vient pas après l’œuvre mais reste produite, dès l’origine, par l’avènement et la structure de l’œuvre. À l’origine il y eut la ruine. À l’origine arrive la ruine, elle est ce qui lui arrive d’abord, à l’origine. Sans promesse de restauration”. |

| ↑4 | Miguel Ángel Hernández, El arte a contratiempo. Historia, obsolescencia, estéticas migratorias, ed. Akal, Madrid, 2020, pág. 56. A capital book for understanding contemporary art from the point of view of obsolescence, a book from which I have made a montage of quotations here. |

| ↑5 | Ibidem, págs. 44 y 49. |

| ↑6 | ”A process of subjectivation is thus a process of disidentification or declassification. Or to put it another way, a subject is an in-between, a between-two”, in J. Rancière, Aux bords du politique, Gallimard, col. Folio, Paris, 1998, p. 119. |

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)