Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Some people inherit values and practices as they might a house they inhabit; some of us have to burn down that house, find our own ground, build from scratch…

Rebecca Solnit

During adolescence, the desire to have been born into another family hits hard. Although it is most pronounced in this period of life, it does not die there. Who isn’t tempted to speculate how in other circumstances they would shine more, laugh more, have more amazing adventures, thus fulfilling the destiny they always deserved? What this yearning reveals, however, is not so much the promise of success as the opportunity to be someone else: the same person but different. I don’t know if I still have this desire, or if I am still under its effect, inspired by the possibility of being someone I am not. To be a different person, different people, to be everything I want to be.

A few years ago I saw Coraline, a film in which the protagonist finds a disturbing world behind a small door where another version of her family lives. There, her false parents have time to play, grow beautiful flower gardens and take her to the circus. Just before the movie punishes her for wanting a life that fills her with curiosity, she realizes that there is a catch. What is etched into the memory of those who have seen Coraline is that the price the girl must pay is her eyes: a witch wants to replace them with buttons, which she sews into the empty eye sockets of the children she traps. This is not a minor fact, as eyes serve as a metaphor for imagination. The lesson is very clear and, after defeating the witch, Coraline returns to her normal world through the same little door. What is hard to believe (and what really hurt me) is that she returns to her life so calm and so obedient.

For better or worse, one can invent a family constellation different from one’s own while still being authentic, undo the ties of birth, adopt another sign. I said “for better or for worse” because what matters here is not the results. On the other hand, betraying one’s origin (and destiny) is also a way of giving our relatives and ancestors a different life. Isn’t that a great gift? Rebecca Solnit tells how something like this happened with the photograph of a great-grandmother whom she never knew: her image, behind the silver gelatin, took the place of the unimaginable. “Having someone so close to you who represents mystery is in itself a gift,” says Solnit. Over the years, the photograph gave birth to different stories, to which other, contradictory ones also appeared and gave rise to new stories. It was Solnit’s “critical, well-read, radical” aunt, the one in charge of preserving the family photographs that “more than serving as props for a stable past, were ghosts and fictions transformed according to the needs of the present.” For the writer, truth came from this way of relating to the facts, in which she placed her hopes and interests.

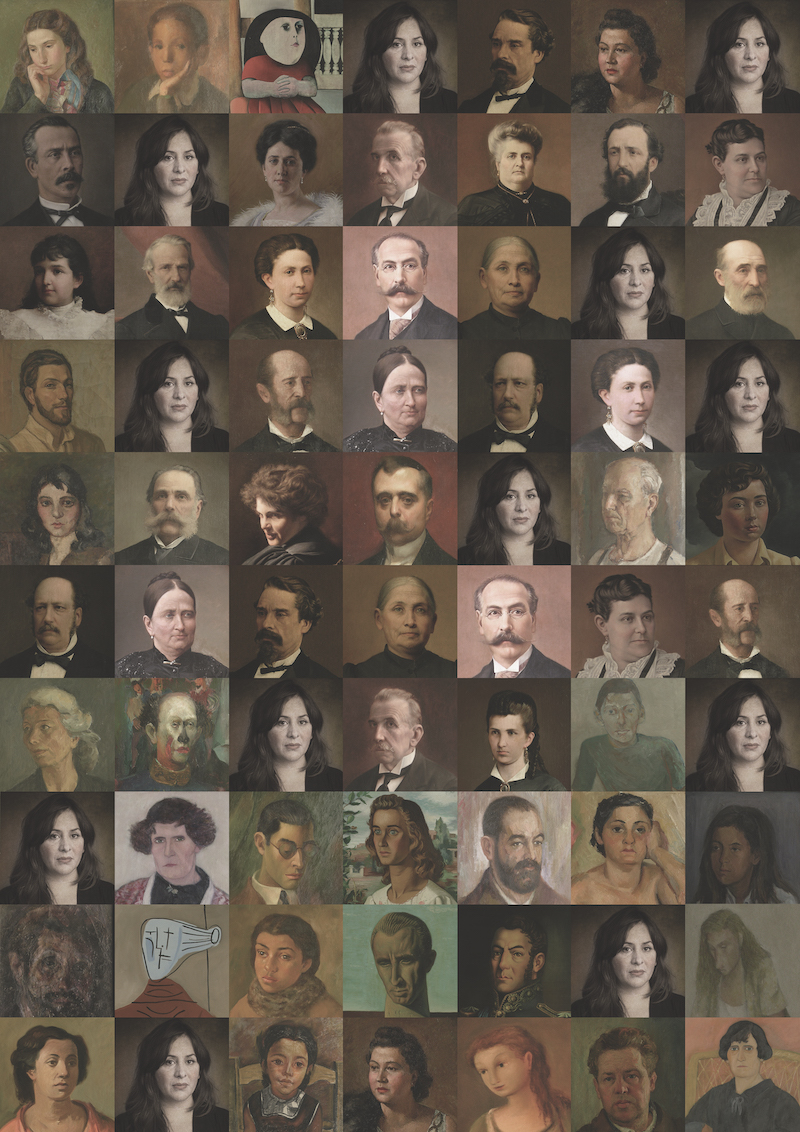

Some time ago, Sofía Torres Kosiba had an exhibition in the Genaro Pérez Museum in Córdoba (Argentina) in which she invented an entire family. Using a selection of portraits from the museum’s collection (to which she added her own), she put together a family tree and recreated some of the portraits in video-performances starring herself. The narrative she constructed confused the history of her own ancestors with the history of art, mixing a family constellation with a picture album. She titled the work “Extraños. Un profundo resonar” (Strangers. A Deep Echo.) A large part of the portraits in this collection belong to the wealthy families of Cordoba at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, and thus the genealogical tree extended its branches towards a past in which Kosiba mixed fiction, ancestry and heresy. The result was an installation that belongs not within the category of speculative imagination but rather historical hallucination.

Sofía is a baroque artist in the strictest sense of the term, that is, faithful to making and exhibiting her Capriccio in which exaggeration springs from spirit and matter. Her poetry moves like a snake between sensuality and terror, sustained by the feverish work of an enchanted conscience. Humor, though, is the key element, the philosopher’s stone that transforms hopes for transcendence and pretentions of solemnity.

But back to the family tree. Among its branches is Cabeza de judío (Jew’s Head), an oil on canvas of the well-respected Emilio Caraffa, who now plays the sinister uncle, patriarch of this fictional family. In the video performance where Sofía embodies him, her uncle growls and mutters with his eyes closed, choked by his own beard, irrepressible in his pathetic figure. On his right is Elina Oliva de Igarzábal, his sister, married to a rich man and wearing jewelry and a fur coat. In the video, Elina’s chest shakes behind her tulles and furs while singing a punk song: “She never went back to Fabian’s bar and stopped fighting on the soccer field on Sundays. You’re no longer the same, you’re now are a Federal vigilante.” Below her there is another woman, located between the portraits of her two lovers, brothers. Now personified by Sofia, she chirps like a bird as she moves her hands tied together by a pearl necklace. The green of the “original” oil painting is an emerald that reminds us of Fragonard’s rococo swing in a bucolic garden upon which a lady in pink swings. Sofia’s smile in the video, her pink dress, are also reminiscent of that 16th century lady. The portrait of Etelvina Garzón Funes, another patrician from Córdoba, is taken from behind, with an almost imperceptible bruise on her face. From this discovery, Sofía embodies Etelvina murmuring like an insect, the crazy woman from the attic who turns her face to us like a wounded animal. The light and reflections of all these images is as powerful as her chiaroscuro, the artist bringing them from the past to penetrate the wigs of the characters, the silk taffeta, the pearls, the pixels. They are works with flesh, breath and voice (Sofía sings, howls, whispers).

The performing arts involve inventions of reality, though art itself is not a mere illusion but rather the material elaboration of a fantasy set in the world. Everything I said before leads to this: in the staging of her work Sofia understands the moral of “careful with what you wish for” (which, misunderstood, condemns us to a vital and poetic reduction), although she gives it a new meaning. Wish for more. Difference opened my eyes, open them more, nobody is going to gouge them out. Where there is too much, invent everything again. These are works capable of giving birth to a horn on one’s head or in one’s heart, and to include non-humans in our family. They allow us to become multiple women, yes, but also other beings (“animals, insects, shamans, divas and ladies,” as Sofia says in her statement). This is where the post-human monster is born that sings: “a butterfly/I transform myself… shower of stars/I transform myself…I contradict myself/I transform myself…I’m all things/I transform myself.”

Emilia Casiva is an editor and writes about visual arts. She co-directs “Unidad Básica”, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Córdoba and its publishing label. Occasionally, she acts as curator. What she wants is to know something about herself (and others) in front of the images. Then forget it, and start again. In between, something is transformed, a destiny is twisted, the exclusively human is disarmed. Lives and works in the city of Córdoba, Argentina.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)