Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Two books. Between them, an exhibition. A triangle, that articulates the prism through which to look, from the present, at the moment conceptual art emerged. The three elements direct our gaze at works that today form part of the classic corpus of 20th century art. Drawing our attention to names that are already familiar. They place within our field of vision exercises with language that in their day were revolutionary and today integrate the creative abc.

The exhibition is Materializing Six Years: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art . It forms part of the program at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, at the Brooklyn Museum in New York that has been open to the public since September 2012 until the middle of February. The books to which I’m referring are the catalogue for the show and the first large monograph dedicated to conceptual art: the book that the critic and curator Lucy R. Lippard wrote in 1973, Six Years. The Dematerialization of the Art Object.

Six years was received in its time as an out of the norm publication. A book produced by a young woman, published at the beginning of a convulsive decade for New York, a city agitated by anti-Vietnam protests, the emergence of feminism and well over a decade of mobilisations from the civil rights movement. The intention of the text is to show the variety of registers that fitted under the label of dematerialised art, as Lippard defined it in the article she published in “Art International” in 1968, along with John Chandler, The dematerialization of art. As a consequence of the inherent plurality of this art, Lippard opted to avoid the classic anthological monographic format and instead compiled into a publication; notes, documents and comments on the works, exhibitions, and events linked to this form of art. Because it is not possible to isolate a definitive characteristic, common to all, nor to theorise the movement as if in the form of essay, following a single thread of analysis. An extensive album of cuttings that the author herself said she didn’t expect anybody to read from start to finish.

The catalogue of the show coexists well with the other two elements. With essays by the curators, Catherine Morris, Vicente Bonin and Julia Bryan-Wilson, it contextualises the show within the historic time it refers to, while at the same time questioning its relevance in the present. The analysis by Bonin, about Lippard’s relation with writing draws as much on Six years and the dematerialisation of the art object, as a selection of texts that serve to document the transformation that the thinking of this North American critic experiences during the decade of the seventies. For example her migration from left-wing activism towards the mantle of feminist practices. On the other hand, Bryan-Wilson rescues one of the original questions of feminism in the seventies, the one that questions the place of women within art institutions: in her essay she reminds us that in its origins, for Lippard, the conceptual formed part of an emerging alternative network which it was hoped would reconfigure the art world.

At the end of the decade of the sixties, and in harmony with the work of the conceptual artists, Lippard employed her work with text, as a precept for the curating of shows. For her series of shows with numbers, for example, she sent written instructions to the artists selected with the aim of guiding the production of the works. But these are not practices that are exclusively hers. The gallerist Seth Siegelaub also curated various exhibitions in magazines at the end of the sixties, including artists from the conceptual circle. The book, Six years. The dematerialisation of the art object, was seen by the public and the author as an exhibition on paper. Today the Brooklyn Museum takes charge of this pending task of art history: to follow the guidelines written by Lippard and take the book as a paradigm with which to articulate an exhibition.

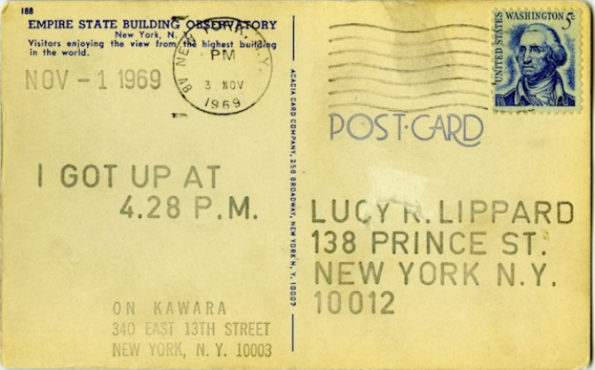

The result of this experiment has been a show made up of a large majority of the works that in their day carried the weight of lending form to a revolution in the artistic language. With more than one hundred and seventy objects, representing the work of some ninety artists, this exhibition shows the public what is considered to be conceptual art right at the moment of its appearance. Early pieces by Sol Lewitt, Daniel Buren or Joseph Kosuth; documents brought by Lippard about Tucumán Arde (1968) from her trip to Argentina; the Following Piece by De Maria (1969), the series of postcards I Got Up by On Kawara (1969), or the Cremation Project by Baldessari (1970) are just a few examples. As I said before, these are all already classics. We’ve seen many of them already. In principle this show doesn’t have to be different from any other historicist anthological exhibition of a movement that is already from half a century ago. However, if the pieces entertain us in the recognition of the origins of our current language, by being tied to a book, the exhibition in itself is a totally pertinent gesture.

The relation between the task of the writer and that of the curator has for a while now occupied the centre of the debate about the exhibition as a medium. Books and exhibitions are drawn to each other because in some way or other they complement each other. This also isn’t a new debate. The sixties, is also when curating begins to be thought of explicitly as a critical practice. Today we continue to think like this, but already beyond the novelty of the question. Recently various centres have spoken out about the possibility of pairing shows with texts, of writing them at the same time, or of thinking them one after the other. We find for example, the work of curators such as Tirdad Zolghadr, half way between curating and writing; or in Spain, Contarlo todo sin saber cómo, a work by the curator Marti Manen for the Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo in Móstoles. In this case, the exhibition comes into the world along with a novel with the same name. Though both are autonomous, the writer articulates them around a series of common elements. The experience, when both are seen, opens up another dimension. A relation similar to the one that arises between the book by Lippard and the design of the show that takes it as its model.

At the end of the seventies Lippard begins to take herself seriously as a writer. In her endeavour to reconcile conceptual art with feminist thought, at the time held to be incompatible by academia, critics and artists, she moves closer to the work on text that is being carried out by French feminism. This posture doesn’t just influence her writing (critical and fiction) but is also reflected in her work as a curator. From then on her curatorial discourses are fragmented and to a certain extent subjective. Distancing herself from the model of the solo exhibition of relatively consecrated male artists she mutates towards choral exhibitions of works produced by women who were frequently not represented on the institutional circuit. The exhibition that we see today in Brooklyn heeds this conciliatory gesture of seeking the writing of a subjective and fragmented map that describes the moment that conceptual art emerged.

As the curator of the exhibition, Catherine Morris, says in the catalogue, right from the start dematerialised art is presented to the public as something without formal gravity, always favouring the simultaneity of constructions that were in principle not related and without points in common. That is to say, from the beginning in the discourses about production, critiquing and curating of this type of art what is primary is the coexistence of compatible elements in their difference, as opposed to the unity and formal consensus that characterises, for example, the subtexts of abstract expressionism in the previous decade.

In 1973 a book is published that wants to show the public what a new art with revolutionary spirit looks like. Today these already representative pieces are taken and placed in the gallery of a museum. Since shortly after its birth the conceptual succumbed to the power of the institution and the art market, this exhibition doesn’t kill anything that wasn’t already dead. Like any other exhibition about a historic movement, it brings objects from the past to write a specific history about it. However, what is undoubtedly true is that it doesn’t just remind us of the origins of the language we talk nowadays but also recounts part of the history of what now seems such an everyday gesture: how the discourses of curators are born in some cases from the affaire between books and exhibitions.

Paloma Checa-Gismero is Assistant Professor at San Diego State University and Candidate to Ph.D. in Art History, Criticism and Theory at the University of California San Diego. A historian of universal and Latin American contemporary art, she studies the encounters between local aesthetics and global standards. Recent academic publications include ‘Realism in the Work of Maria Thereza Alves’, Afterall, autumn/winter 2017, and ‘Global Contemporary Art Tourism: Engaging with Cuban Authenticity Through the Bienal de La Habana’, in Tourism Planning & Development, vol. 15, 3, 2017. Since 2014 Paloma is a member of the editorial collective of FIELD journal.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)