Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

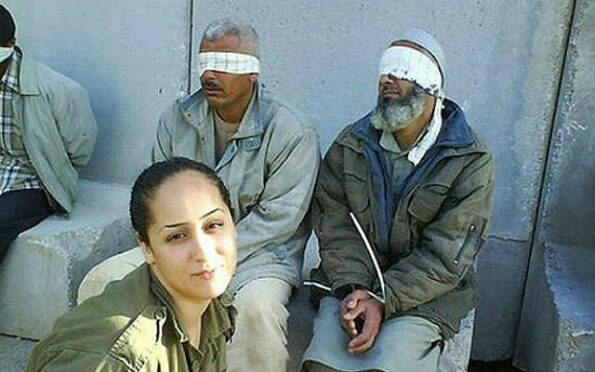

During one late summer, second lieutenant Eden Abargil uploaded images to a private Facebook album titled Military, the most beautiful time of my life. Despite her claims for the aesthetic sublime, most of the photographs were rather mundane. Paperwork being conducted in an olive uniform. Hugging embraces with other soldiers turned friends. Boring platitudes of bureaucratic ordeals and then, all of a sudden, a picture of her gazing into the camera, posed alongside unaware blindfolded detainees. Posting office pleasantries next to abuse, her album served as a reminder of how photographs produce moral authorities; a clear sense of agency is afforded to those who produce the photograph, while robbed from those forced to partake in them. When the second lieutenant looked at the photomaking machine with a smirk in one of them, it was no coincidence that she positioned herself in front of three handcuffed and blindfolded Palestinians backed up against a colossal concrete wall. Perhaps it is no surprise then, that this exact infrastructure, that was made to keep some removed from the sight of others, served as the background for a photograph in which the present is still made absent. For another such photograph, Abargil sat across another unsighted man who she ridiculed given what he could not witness: her blowing him a kiss. Her degenerate documentation was not private. What made her self-published documentation all the more degenerate was the audience engagement it produced. Friends made sarcastic comments on the public platform, suggesting that Abargil is the sexiest when she poses like that, and that one of the arrested men must have a hard on for her.

Yet as much as this reprehensible conduct is regarded as acceptable within the militarised culture in Israel, other international organisations and newspapers came to disagree with how it was spent. Abargil was scrutinised across the board. Unable to deal with the scathing responses from both near and far, the soldier snapped under the pressure. Expressing an average cognitive dissonance of being both victim and aggressor that has become all too common, Abargil claimed to the interested press that her photographs were made without malice, and that there was no statement in those pictures that were taken around the Gaza border where those documented men who were suspected of having illegally crossed the wall. For her, the photographers were a commonplace reflection of the military experience. But at the same time, her self made innocent narrative of the event was often interrupted with her sudden fits of rage. Abargil commented how she hates Arabs and wish them the worst. Foaming from her keyboard, she confessed how she would gladly kill and even slaughter them. Abargil concluded that she cannot afford that Arab lovers would ruin the perfect life I am living. What is important to highlight is just how much her outlook and digital postcards served as a watershed moment. Not for the violence depicted in them; blindfolding as a form of punishment existed for centuries now. Yet that mode of organised abuse was oftentimes kept out of sight –left in the societal margins of the firing squads and prison camps; taking place behind other separation walls. But to elevate such violence into a glamorised spectacle that one could share and be proud of was new. Her triumphant malice served as a snorkel to accumulate social capital. Torture now had the added function of existing as a device for generating clicks and likes; one that will remain on show from now until forever.

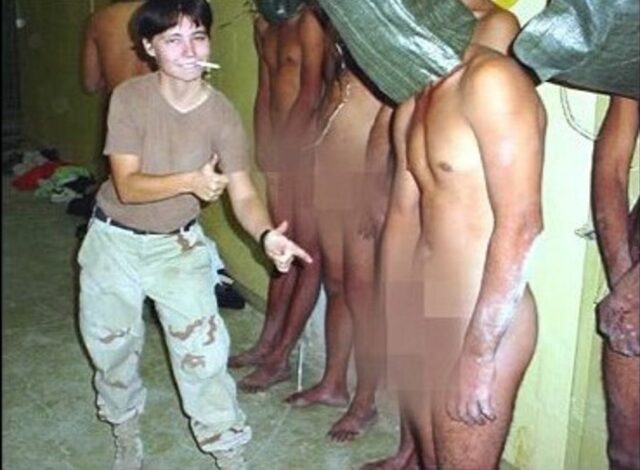

Lynndie England Either doing the ‘thumbs-up’ gesture or signalling that she is holding a pistol aimed at the penis of the hooded naked Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib (en.wikipedia.org, 2003)

The images of Abargil were often compared with another viral oppressor, Lynndie England. Just as disgraced for photographs of her posing with big bright smiles and thumbs up next to naked corpses and agonising hostages in the Abu Ghraib detention center during the supposed global War on Terror, England, unlike Abargil, was discharged from the United States Armed Forces after due process. Her images were leaked rather than shared out in the open, but both served the exact same function. Making those photographs is part and parcel of the humiliation process. Whoever retains the will to determine how its subjects will be presented controls their social value. Hence the argument made by Phillip Gourevitch, that republishing such images exhumes and repeats their disgrace. But when Abargil was asked about similarities with her Yankee counterpart, she responded that all the world compares me to her. It’s deranged. Despite their mutual libidinal passion for the torture and slaughter of Arabs, Abargil retracted her actions once again and swore that her pictures were made in good faith and not like the American one. But the two renegade soldiers shared more than just a burning desire for debasing others and related banalities of evil.

While both Abargil and England have abused subalterns to a lesser and greater degree, the anonymity of their victims is still identical –blindfolded men who will forever remain as unidentified others. Depriving them of their identities and biographies, reducing their entire lifespan into its loss is itself part of the torture process, no less than the creation, dissemination and circulation of their images. Telling from their depraved showmanship, it is obvious that violence must manifest itself as a spectacle in order to receive a moral dimension. Humiliation does not exist in a vacuum. Both in the case of Abargil and that of England, it requires and demands an audience in order for it to take place and for the roles of abuser and abused to remain fixed. What that means in practice is translated into the media insistence to converse with Abargil and England rather than their subjects. When taking moral considerations out of the conversations, questionable motives to redeem soldiers rather than humanise their victims is perhaps sensible given the composition of the photographs themselves. For all the generous political ambitions we might hold, when a photograph presents us with a mobile and recognisable person with clear expressions, that subject is easier to engage with and respond to than some blindfolded and handcuffed others. Plundered of their human features, those documented as sightless and with tied limbs appear to be more like corpses in the making.

Image from “Red Wolf And The Surveillance State: Investigating The Human Rights Implications Of AI-Powered Facial Recognition Technology In Palestine”. The Dialogue Box, May 19 2023 by Junaid Suhais

Caging the Palestinian body politic in the most literal sense. When we likewise make eye contact with the soldiers, we are somehow made culpable in their crimes. Put in more general terms, photographs cement a permanent and unchangeable relationship of the photographed with the photographer. When the subject in the photograph happens to be one person or a group, their awareness and reaction to the camera is quintessential to determine their emotional state and basic permission. When that form of basic representation is stolen from them, when their faces are covered with cloth and their mobilities are plundered, their will is reluctant and confined to the entertainment of others. Gaze deprivation of that sort perverses the most basic moral component of photography: consent. Numerous countries around the world have illegalised taking and sharing photographs of others when it shows their helplessness for that exact reason –affording them a replied gaze would grant them equal footings and ensure their selfhood.

Gaze deprivation has since then exploded into gargantuan proportions. Thanks to algorithmic surveillance and the supposed impartiality of artificial intelligence, the facial recognition system known as Red Wolf have proliferated in occupied territories and undesirable territories. Abargil and England are in this sense personified precursors to this newfangled mode of societal control. Persecuted subjects are in a constant state of being either blinded or watched. No middle point exists. Domination plunders the basic freedoms attributed to the senses.

Israeli soldiers censored next to a detained Palestinian child, October 2010

Violence is a currency within militarised societies. Wherein the more violent acts one performs, the more such actions will be rewarded in economic, social or sexual tokens. Dehumanization is socialised and legitimised thanks to such widespread spectatorship. Gaze deprivation is now a systematised affair. Just some months after the second lieutenant opened the floodgates, an image of four soldiers taunting a blindfolded Palestinian girl was shared to more useless shock. What was unusual in that image was the decision of certain websites to anonymise the gunbearing men alongside the blinded girl.

Deprivation of identities highlights the oppression of some and protects the rights of a few. New images arrive from American Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facilities. Images that reverse the roles. Nowadays, wards are the ones masked while the prisoners are exposed. This shift indicates the immense technological developments of the past two decades. Due to reverse image search engines and face recognition databanks, retaining the right to hide a face is paramount in protecting civil and digital rights. Placing security cameras in each corner and biometric scans at each checkpoint makes the occupation omnipresent; inescapable. Much like the hooded executioners of the middle ages, hiding in plain sight has once again become a right afforded just to state sponsored butchers.

Police officers guard the second arrival of inmates belonging to the MS-13 and 18 gangs in Tecoluca, El Salvador, on March 15. El Salvador’s Presidency via AFP – Getty Images file

Detention centres such as El Salvador and Sde Teiman now blindfold hundreds of hostages for long periods of time in subhuman conditions. More than simple spontaneous conduct on the battleground, the deprivation of gaze is now a national compulsion of the utmost strategic importance. Making the dehumanised others unaware of time and space means removing them from the quintessential pillars of existence itself.

(Featured image: Israeli soldier Eden Abargil posting next to Palestinian detainees on her Facebook profile, 2010.)

Adam Broomberg (b. 1970, Johannesburg) is an artist, activist and educator. He currently lives and works in Berlin. He is professor of Photography at Istituto Superiore per le Industrie Artistiche (ISIA) di Urbino and Practice supervisor on the MA in Photography & Society at The Royal Academy of Art (KABK), The Hague. His most recent work “Anchor in the Landscape” a large-format photographic survey of olive trees in Occupied Palestine was published by MACK books and exhibited at the 60th edition of La Biennale di Venezia.

Ido Nahari is a writer and researcher currently pursuing his doctorate in sociology. Previously an editor for the street newspaper Arts of the Working Class, his writing has appeared in numerous journals and magazines. He has lectured in various museums and academic institutions across the United States and Europe.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)