Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

When Robert Smithson headed to Western North America to work in the open space, he left behind the neutral, aseptic limits of the gallery, to liberate himself with a change of scale and perspective. One of his references, more influential for him than even Duchamp, was Frederick Law Olmsted, the creator of Central Park and Prospect Park, amongst others, who imported the ideals of the English landscape movement. Who, unlike their French colleagues, saw in nature a source of exuberance that was impossible to restrict to any form of geometry. This Franco-British difference between manipulation and letting flow is repeated in the natural and the cultural, in the rebuilding and preservation, epitomized by the differences between Viollet-le-Duc and John Ruskin. Although these may seem frivolities, these distinctions suddenly become crucial when we relate them to national concepts still notorious today. The idealized landscape versus the controlled landscape, the mirage of a framing of the wild and the forced rational perfectionism of the environment, continue to reflect the two colonial idiosyncracies of the Empire and the Republic. In the French line, one Catalan appendix stands out, the embodiment of faux gothic and Northern-Mediterranean fantasy, the architect and president of the Mancomunitat of Catalonia, Josep Puig i Cadafalch.

Writing about Olmsted, Smithson comes to view the world as an assemblage of matter and energy, of relations in motion, hence, the intent to capture through landscaping or lyrical poetry always denotes a stance that separates the human from the natural. The representation of the world implies a use of the land. In this way, linear perspective serves as the base of modern thinking and colonial expansion. The position of the objects in relation to space-time, their properties accessible and quantifiable, facilitated the ordering and domination of other the mineral and biological making tangible a cartography of the assailable. Colonial power finds in the map and the grid a form of imposing their vision of the world. The efficacy of pillaging owes a lot to systematization and the infrastructure applied to the irregularities of geographical accidents. This same capacity to mobilize participates in the impetus for social reformism and of some utopian socialists: if we are capable as a species of dominating the world, why not do so in another way? There go Ildefons Cerdà, Patrick Geddes, Cebrià de Montoliu, Yona Friedman!

Following history, Cubism would be the European move away from this expansion, the abstract and analytical complication that announced processes of questioning and class struggles for emancipation and the transformation of the compositional planes of the nature-human ecology. Smithson, however, writes in the sixties and seventies, when first Minimalism and then Land Art brings new dimensions to a generation. Smithson leaps beyond the cultural miasma that is New York, the sculpture garden, the pastoral landscape and the suburban wasteland – even though the latter held a special familiar connotation for him and served as a reference (A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic) – to get stuck into the elements and “physical contradictions inherent in nature”. It is worth remembering, however, that though the gesticulation of Land art has typically been characterized as masculine, Smithson’s intention was to offer a glimpse of a spiritual need to commune with nature. At a singular moment in the future of our ecological future, the severing of the gold standard by the Federal Reserve in 1971, and the petrol crisis of 1973, such events marked the beginning of a cycle of alterations in which we are still immersed.

To talk of geography, the writing of the earth, the study of the physical properties and relations between peoples and environments is today a question of urgency that ricochets through any intellectual activity, social field or political discourse. In the face of climate disturbance and the extinction of species, the human being is living an exceptional time. On the one hand, economic production is inseparable from nature-human exploitation, from pollution and a deranged consumption of more or less refined plastics that are to a greater or lesser extent embedded within the food chain. The Anthropocene, or as Donna Haraway has referred to it the Capitalocene,will leave behind an indelible imprint of rubbish and modifications to atmospheric norms. On the other hand, the displacement of the human being as the primary source of interpretation of the world is beginning to be a fact more than a distant dystopia. Not just through technological evolutions but also in the priority given in recent philosophy to the emergence of autonomous entities whose capacity to generate intelligence, memory, connectivity, and development lead to the loss of human supremacy. Although it sounds somewhat positive, by definitively breaking with the dichotomies of modernity (culture-nature, subject-object, masculine-feminine, homo-hetero, human-machine, human-animal, primitive-civilised, etc.) and giving recognition to non-human people, other mammals, or the gaining of environmental rights, it also implies a loss of scale and proportionality of humans. In favour of systems and techno-commercial, logistic constructions that are only going to bear in mind the particularities of millions of beings- who think of themselves as special and unique – to the extent of their commercial yield. In turn, these two tendencies remain an echo of the conceptual and political acceleration that stimulates our present. If the Indignados or Occupy Wall Street were the last expressions of the great anti-global, the next agitation will have to assume another perspective, another scale. To propitiate a new geography that surpasses the categories of the patriarchy, capitalism, Christian social-democracy, to this time, yes, accelerate the rhythm towards organizational effectiveness. If we have the human-technological capacities to confront the challenges of the global ecology, why not do so? Be it because of Varoufakis or Le Pen, Sanders or Trump, the Western political-economic distillery is simmering away.

The vision of the earth of the poet Salvador Espriu, however heartbreaking it may be in the voice of Silvia Pérez Cruz, remains a song to oneself, a song to that which, one day, will disappear with us. All those flats where we have lived, all the faces of our loved ones, all the concrete combinations of matter that accumulate, such as books, photographs and letters from our ancestors, which in the best of cases are handed down from generation to generation, it all participates in the daily entanglement that reproduces, on a minute scale, humanity’s long transformation. Which in turn is a spasmodic response to the movement towards the final destruction of our solar system, our participation in which we are unconscious of, in our day to day. Entropy, the movement contrary to evolution, had for Smithson a particular significance, while energy disperses, the human mind endeavours to fiddle with bits and pieces to compose units that. although fictitious and ephemeral, serve to imagine stabilities when everything flows down the drainpipe of time. Those who in the belief they have conquered the vital coordinates, who gain economic profit in the destruction of geography, be it in a garden, a grocer’s shop, a flat in the Eixample of Barcelona, or a salt flat in Bolivia, live in terror of this perspective that unexpectedly opens up before them, the insignificance of humans in the face of the long-term gaze of matter.

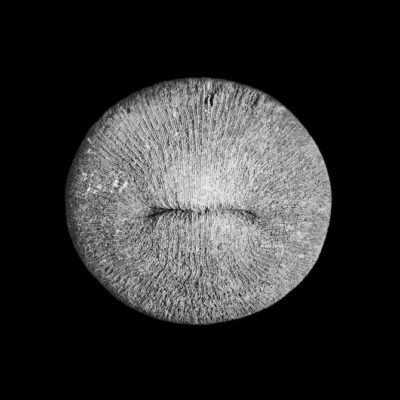

The photograph illustrating this text belongs to a series of portraits of fossils made by the Japanese artist, Akiyasu Shimizu, who lives in Berlin. In particular, this is a Cunnolites Elipticus, close in spatial origin, from the Sierra del Montsec in Lleida, but with a remote provenance in time, the Late Santonian Cretaceous (approximately some 85 million years ago). The fossil is the exact same example used by Quentin Meillassoux to indicate an existence beyond human subjectivity that can only be captured through science. While his position has been contested from different angles, it still opens up a perspective that relocates the human being in a state of isolation, or to put it better in a state of doubt, incapable of apprehending the surrounding reality in its entirety. The entities which we relate them to no longer have an agency to make them actors of the present, so much as they retain for themselves the mysteries of their substance, impossible to decipher from our own experience.

Xavier Acarín is fascinated with experience as the driving force of contemporary culture. He has worked in art centres and cultural organizations both in Barcelona and New York, focussing in particular on performance and installation.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)