Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Picture a landscape. It’s the sea of Beirut. Light is shivering on the delicate surface of the water, kissing the horizon orange. You try to focus your gaze on a wave that does not hold still long enough to be remembered. Instead, it escapes the stillness of meaning as it races to its reckoning on the shore of the city. Imagine all of this beauty, the infinity of this moment, captured in a frame. The picture is but a fraction of the landscape, a part of it that can never encapsulate the view in its entirety.

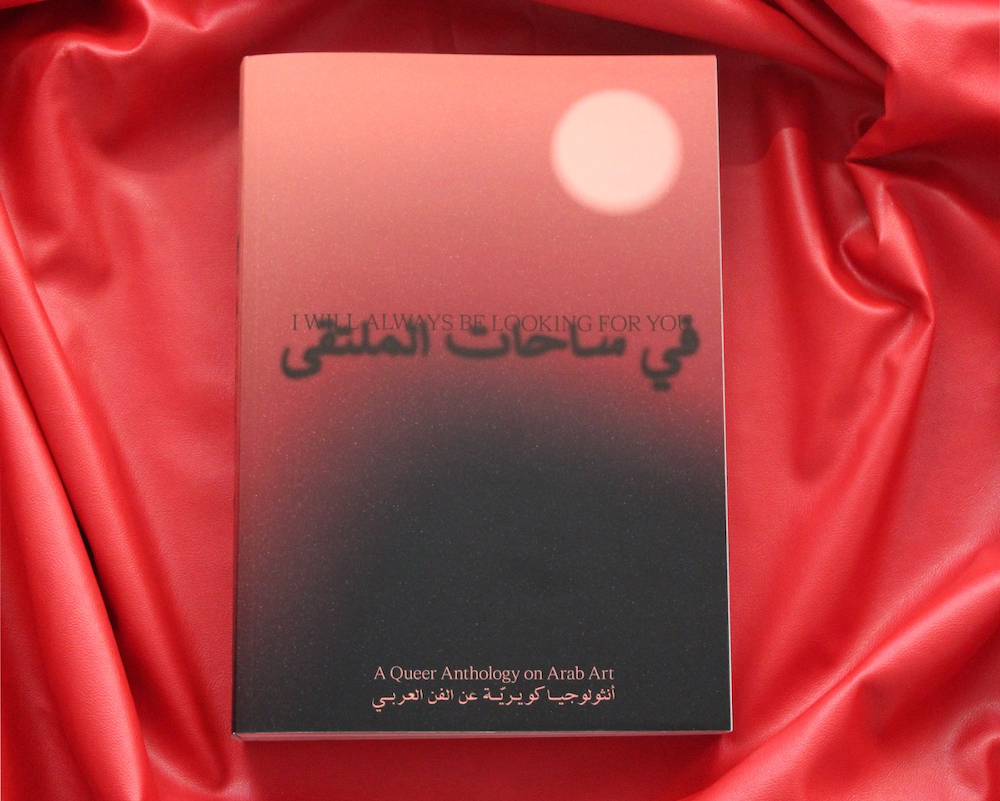

I Will Always Be Looking For You is a picture of the queer Arab.

In the early summer of 2020, Dayna asked us, Yasmine and Nadim—the editors of this book, if we would be interested in working on a research project to gather a selection of queer art from the region. The conversation lasted the length of a cigarette: we accepted almost right away. Before embarking on the research, we asked ourselves a few important questions: what will this archive look like, what should it do, and who will it be for? We wanted to present a body of work that came straight from the guts of the region—how Arabs have been producing queer works from within the homophobic smog of Arab cities (still preferred by many over the pinkwashed air freshener of the genocidal Global North). We wanted this book to look beyond an Arab’s gender or sexuality in art, and into the mechanisms and codes we use to speak of such notions. I Will Always Be Looking For You centers in its methodology a refusal to comply, whether to the expectations of the readers, or to the traditional modes of research and publishing.

And so, this publication was created out of a desire to look for queer Arab art without attempting to seize it. It does not endeavor to define or legitimize it as a category, or examine its paradoxical framework as exceptional. Rather, it is an exercise in observing what the merging of queerness and Arabness can look or feel like in an artwork, and letting it take shape, dissipate, and transform.

We began by looking for our queer Arab ancestors. In our belief that they existed—in our conviction that, if they have lived like us, then they were probably many—we remembered them. We had the desire to find their names, faces, and locations. After this initial desire came a transformative realization: our queer ancestors were not only forcibly absented from historical archives; they may have often willingly concealed their spatial and temporal contexts to ensure their survival. The act of “willingly hiding” was, and still is today, an indirect forced erasure. What is also true is that the expressions and languages of our ancestors, like ours today, were produced in duality with (and resistance to) this continuous erasure and omitting that reality from the rendering of our lives would mean distorting the truth. Our search for these contextual indicators became trivial.

Love and queerness have a history of being tongue-tied around each other. To profess both can fulfill yet endanger what each holds. Self-combusting. It is also why much of queer love is hidden like “this kiss [that] marked our lips and left us” in Musa Al-Shadidi’s essay on Akram Zaatari and Mahmoud Khaled. Yet al-Shadidi shows us that, where it hides and who it hides from, is also its power in dismantling queerness from the western politics of visibility. If you want to search for the queer Arab in the archive, as you would in this book, you will always be looking for them. As such, if we were to look into queer loving/living, we needed not only to look away from the normative dominant narrative, but to also look differently. We could only reach our past by sifting carefully through history for queer remnants willingly left for us to find, without disrupting the mechanisms of protection that queers, before us, had utilized for their continuation.

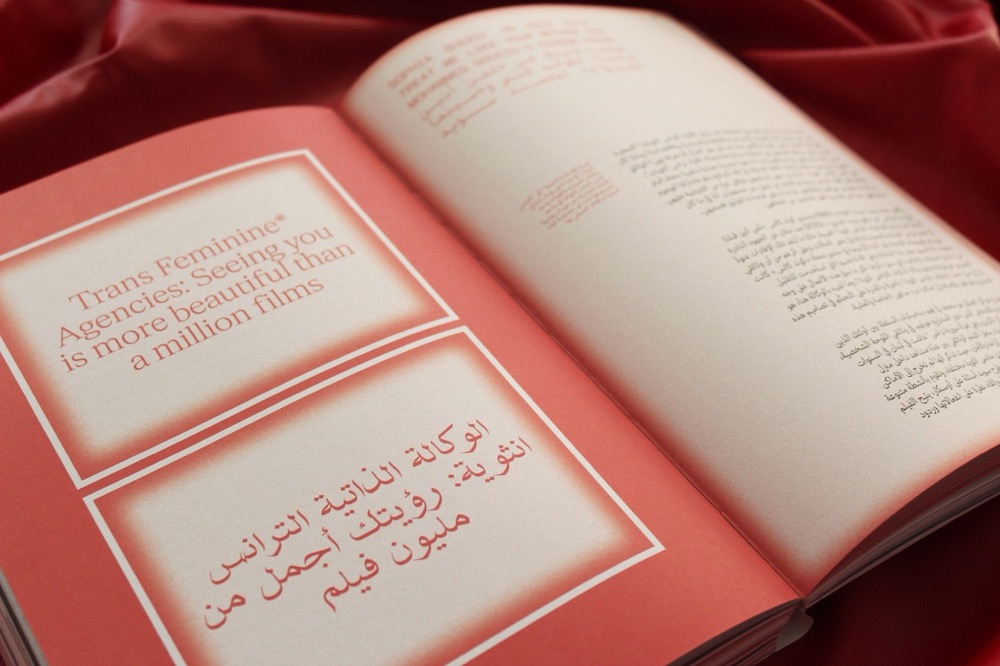

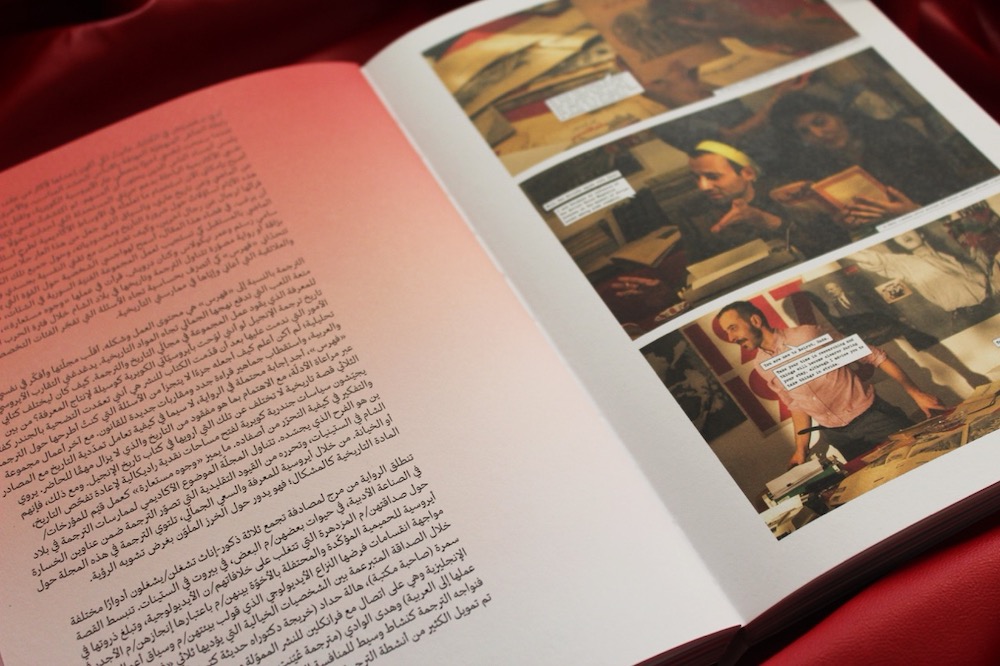

With that methodology in mind, we took on the difficult task of curating what would be included in this publication. We carefully selected a series of artworks that illustrate how versatile queerness can be and invited writers from 13 different Arabic-speaking countries to respond to the visual artworks and artists we paired them with. Arab Queerness was presented to the writers as a theme to tackle and refute, and they have all made sure to do so with utmost pleasure and mischief. Their positions engage with Arabness in different ways: some self-identify as Arab, some reject it, some are shaped by the forced Arabization of their communities, and some twirl through all these identities. The contributors wrote not only of queerness, but queerly. They played with chronologies and geographies, with words and their meanings, names and even dates, and heavily leaned on imagination when looking at both the past and the present. They personalized the texts with nods to dark theatres, forgotten TV shows, bright exhibition rooms, cafés, markets, books and songs, beaches, towns, and cities. Spaces that have witnessed our passionate love and unwavering determination, where our queerness once was and still is possible. The result is a book where queerness is not always present, exposed, and interrogated, but it is constantly manifested, made to come alive in unexpected forms through the writings accompanying the works. What you get out of this book is a dance, and it changes every time. We hope you allow it to change with you.

The book took five years to complete. The port of Beirut exploded on August 4th, 2020, one month after we launched the research. In 2021, Gaza was being bombed in parallel with the evictions in Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem, imposed by the Zionist occupation in Palestine. In April 2023, war erupted in Sudan. Six months later, in October, the full-scale genocide in Gaza began. That same month, Lebanon came under bombardment, an aggression that escalated further by September.

Saying that it was difficult to work under such circumstances leaves a bitter taste in the mouth. We will never be able to explain the immense grief that we have been feeling. But what we can clearly express is that the Arab is queer in their independence from the colony and its consequences on our evolution. Shedding the skin of occupation is how we chase ourselves, and our queerness, back into being. The chase in all directions is necessary. We have existed everywhere on earth despite the Empire, and our existence has been most endangered under occupation and colonization. Our histories are intertwined with the land, and with all indigenous people who have fought for their right to exist freely as they are, where they have always been. Our histories are a witness to the hatred, violence, and dispossession that all of us and our ancestors have had to bear. Loving ourselves, for who and how we are, has to include loving who we have collectively been, who we can one day become, and what our lands can offer for us to achieve that. These notions cannot exist without recognizing that our identities go beyond our sexual, gender, and ethnic expressions. We are so much more than our singular selves. We carry the practices, languages, love, and pain of hundreds of generations before us. We carry the gifts of our land in our skin and hair, in our tastebuds, in our gaze. The land that has churned our accents and song. The land that has made us, and those before us, queer. If Al-Shadidi shows us the power of opacity in queer love, then Ruba El-Melik teaches us about the pleasures in chasing an experience of queer Arab life rather than a definition: “I am free to live in limbo, to redefine and self-invent as many times as I want to. That, to me, is freedom.” If you want a definition of “Queer Arab” then it is this—the chase for freedom in our worlds. If the chase ever becomes tiring, remember we have moved mountains before for our survival, and we will do it again and again, and if possible with pleasure, as Hind and Hind writes on the Qadisha Valley: “Qadisha trails her hand down her thighs to part them.”

This book is a kiss to the land. It is an ode to the way we’ve been together, counting on each other’s love for the other to take a dangerous word out into the light for all to see, but only a few to recognize. It fails at what is expected of it. It won’t tell you what makes an artwork queer, or Arab, but it does teach you about “failure as queer bodily dissent,” borrowing from Razan Ghazzawi’s essay title. The opacity of the hows and whys of making I Will Always Be Looking For You is due to its faithfulness to its title. It does not know what our Arab queerness will look like, but it searches and searches and searches, in twenty-two contributions about thirty-one artists. The most important search is not finding oneself in a glimpse in the mirror and knowing one’s shape. It is the search for our readers—the young Arab queers growing up, our elders, ourselves, our dead, our living, our loved ones. You are our waves, our suns, our shines, our shimmers, our infinity. In the spirit of performer, resistance fighter, and martyr Oscar Al-Halabiye, we say, “Searching for you is more beautiful than a million films.”

Text edited by Ghiwa Sayegh. Photos © Levi Richards courtesy of Yasmine Rifaii and Nadim Choufi

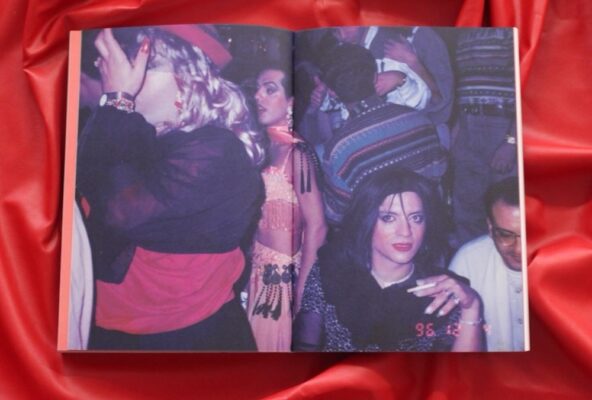

[Featured image: Page from the book I Will Always Be Looking For You – A Queer Anthology on Arab Art by Yasmine Rifaii and Nadim Choufi. Photo © Levi Richards, courtesy Yasmine Rifaii and Nadim Choufi]

I Will Always Be Looking For You – A Queer Anthology on Arab Art can be purchased from Public Knowledge Books, click here.

Yasmine Rifaii is an artist from El Mina, Lebanon. Her practice traverses editorial, curatorial, architectural, and visual arts disciplines. She is the Creative Director of Haven for Artists, a Beirut-based cultural feminist organization, and the co-founder of Al Hayya, a print magazine and online platform dedicated to the Arab woman.

Nadim Choufi is a Lebanese artist and editor.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)