Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In an article for Artforum, Katy Siegel divided the field of art critics based in New York into two large groups: the “thinkers”, irascible cultural theorists mostly related to the magazine October, versus the “sentients”, with the names of Peter Schjeldahl and Dave Hickey at the top of the list. One could look for synonyms for the contrast: professors versus publicists, or the solemn versus the jolly. The quarrelsome versus the intoxicated?

Who picks up on the anecdote is Christian Viveros-Fauné, born in Santiago de Chile in 1965 and settled in Brooklyn for more than two decades ago as an art critic. Viveros-Fauné without a shred of doubt militates in the second group, berating in his essays, endeavouring to find the most offensive adjectives, everything that qualifies for the first, and in general, everything in art that whiffs of boredom, the monograph, speculation or institutional paperwork. Which implies a declaration of war on the legion of professionals in language and material, who, in the last decades, have embarked on the ship of visual arts with distinct results. The climate of this suffocating and jocund war is similar to a focus of resistance against the living dead, where the rival side has the advantage of being the majority and self-replication. However, the solitary adjectives of Viveros-Fauné continue to fly against the tiredness and apathy, coming out of nowhere like sentient fists without arms.

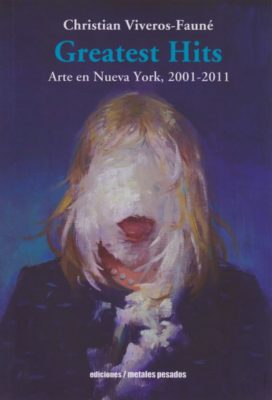

The war bulletin against bureaucracy and lethargy, published week after week in the Village Voice in the form of art criticism, has ended up being anthologised and translated into Spanish by Metales Pesados, once again in Santiago de Chile. The book, Greatest Hits, is a compendium of reviews of the flavour of the day, wrapped in the joy and horror of regularly visiting exhibitions. This breviary of Viveros-Fauné’s campaign through the main exhibition spaces of New York over the last decade, can also be read as an anticipatory testimony: the carefully worded and often loaded phrases that Viveros-Fauné dedicates to his preferred painters and loathed curators (with Lisa Yuskavage and Massimiliano Gioni at the extremes of the spectre) offer a glimpse of artistic ideas shot beyond the self-imposed conceptual limits of the art industry with its institutional organisms and standardised discourses.

As in much of the best “steroidal” criticism that Viveros-Fauné feels at home, in his writings one can hear a wrap on the wrists for the delivery and construction of short term working, though the book has the strange continuity and autonomy of a novel, with central episodes (John Currin, Neo Rauch, the afore-mentioned Yuskavage), minor threads (the devastating critique of various curated exhibitions that were highly commented upon in their time) and moments of self-reflection, like the profile of the admired Schjeldahl and the last text, dedicated to “curatorial surrealism”.

The defence of sensation and a certain ambiguous universalism redound in the unfolding of a planned aestheticism, a critical language charged with subtleties, or better still, integrally composed of nuances, adversatives, acid-sweets and stink bombs with a humanist vocation. But the aestheticism of Viveros-Fauné is not just constituted by its propensity for intensity, the intoxicating, and the beautiful, so be it in this war against tedium, nor does it limit itself to the chosen pictorial canon (a canon visible like a signature, made up of points that are in turn names) His aestheticism is more attributable to the spectral idea of the autonomy of art, behind the lost lines of the current, catatonic theoretic justifications and the language of grant applications. The criticism of Viveros-Fauné occurs in the world of the extraordinary, a world in which art has once again appropriated words, and words have a life of their own when referring to works of art —those things that, “of all things, are the only ones that have a life”, according to Oscar Wilde.

Capricious? Sentimental? In the vocabulary of Viveros-Fauné, these and other such compliments are more than welcome.

Claudio Iglesias is an art critic based in Buenos Aires. His latest books are Corazón y realidad (Consonni, Bilbao, 2018) and Genios pobres (Mansalva, Buenos Aires, 2018).

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)