Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Today we will focus on a European symbol that has existed for centuries, and which in each century has been interpreted differently, known as the Holy Face or the Mandylion, on which Christ miraculously left a print of his face. We will be accompanied by an artist no less miraculous who for a long time created monuments to nothings, columns of a thousand shapes, fantastic spaces in ruins. Our artistic itineraries have already crossed several times but this is the first in which our relationship to this symbol has been consummated.

The Holy Face is a symbol par excellence, occupying the same place in the order of sight as the Eucharist, instituted by Christ at the Last Supper in front of his apostles, does in the Sacraments. The story of its origin is simple: on the Way of the Cross, a holy woman, Veronica, handed Christ a cloth to dry his face and on which his features were miraculously imprinted. The cloth was among the relics in the imperial chapel of Pharos, according to the version of the Frenchman Robert de Clary, a soldier who participated in the ransacking of Constantinople in 1204. The original Holy Face and other miraculous self-portraits left by Christ, along with the Mandylion of Edessa, were later dispersed, sold or looted. Among these was the relic of the crown of thorns, offered to Louis XI of France, for which he had the Sainte-Chapelle built.

The story, since then multiplied by innumerable sources, represents for the history of Christian art its “legend of origins,” in the same way that the gesture of the bride of Corinth does for Greco-Roman Antiquity.

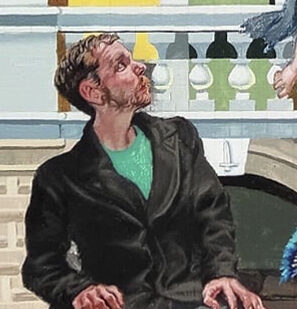

I visited Marc two weeks ago. In the door to his study there was a small slit or orifice through which, before entering, like a voyeur, I peeped. I saw him painting, so concentrated and perfect that I waited for him to finish forty-five minutes later. Exhaling a long breath and putting down his brushes, he came to the door and greeted me as if emerging from the Sinai cloud in which he had been a moment before.

We had a very long conversation, without drinking anything for hours, from which I transcribe the most valuable thing he said:

“About all this I wonder, for I cannot be sure that Jesus Christ existed. Do you think he did, or did not, or is it all the same to you? When you suggested I talk about the Mandylion, the idea of ruins immediately struck me, probably because I was immersed in reading Time in Ruins by Marc Augé. The author states that “art is built on the ruins of religion” and, in fact, that “art itself, in its various forms, is a ruin or a promise of ruin.” It’s a bit like Poussin, who was fascinated by ruins. There is something nostalgic here which, at the same time, contains all the potential of the imagination.

(…) I was incubating an idea in which thousands of possible paths were displayed but which none were clear, and my mind became an Internet search engine with thousands of open tabs. That moment in which we intuit a route, even though we cannot follow it exactly, also resembles a ruin. There are incomplete parts where one can find other routes to explore.

At a time in which official discourse is the end of our resources, the crisis of modernity as explained by the philosopher Marina Garcés in Nova il·lustració radical, in which anxiety seems to paralyze any possibility of critical thinking, perhaps our imagination can find escape routes. Painting has a quality, that when we try to put words to it, cagada pasturet.

There are paintings that are like that, they seem to stop in the middle of the process due to the impossibility of making a decision about the path to follow. They hang in the studio for days, weeks, months. You look at the painted canvas hanging on the wall and imagine what the next step will be, but you don’t take it, you keep the idea waiting, and you go back and formulate another one. This is the case of credo quia absurdum, a painting in which several layers of failed paintings have accumulated. I traced the composition of an architecture in ruins and began to color the masses of shadows and lights. After a few sessions I stopped, and the layers of previous paintings that could be seen on the canvas allowed me to intuit stories. To cover them up would have been a poor job of restoration, it would have limited their possibilities. The painting had become a place in which I could continue imagining within the gaps where the ruins lie.”

[Featured Image: Marcel Rubio Juliana. Dibuix anunciador 3]

Marc Badia (1984) graduated in Fine Arts from the University of Barcelona and has a master’s degree in Artistic Research and Production from the same. He has been an exchange student at Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg (HFBK Hamburg). With an artistic practice focused on painting and installation, his compositions are usually framed by elements that fuse the classic, the contemporary and the dystopian through the filter of the absurd. This juxtaposition of references turns the work into a meticulous collage that functions as a work of uchronic archeology.

Marcel Rubio Juliana (Badalona, April 27, 1991). He expresses himself mainly through painting. He is the author of the exhibitions Vastu Purusha (Racoon Projects, 2023), La resurrecció (Fundació Miró, 2022), Hieros Logos (2021) openstudio curated by Margot Cuevas, El retorn a Ripollet (Joan Prats, Art Nou 2020 award), Surfeit ( Arranz-Bravo Foundation, l’Hospitalet del Llobregat, 2018). In the literary field he created with Víctor Balcells Els músculs de Zaratustra (Passatge Studio, 2016), as well as his recent foray into the world of publishing.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)