Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In grey places the colour of life takes on a strange tint. ‘The End of Innocence’, an exhibition dedicated to Jouko Lehtola, at the Kiasma until 18 August, has a lot of this, that singular tone that emerges from the deepest grey and from life. The route suggested by the museum begins with the projection of a documentary, [[Riitta Riihonen, ‘Jouko Lehtola in Light’ (2011)]] which looks at the last months of the photographer’s life, struck down, like so many others, by an untreatable, virulent and insidious cancer in 2010. Sharing the tears of the moribund, while he(we) listens to a private violin concert in his living room, shortly before he died. As the film progresses Lehtola acquires those eyes that seem to look from beyond the grave. His skin also acquires a fatal yellow colour. A sensibility suggested at the very limits before finally “entering” into his work.

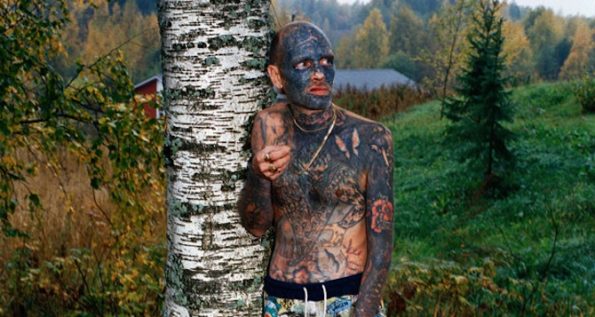

Three spaces, three stages of the life and work of the Finnish photographer. In the first room, a selection of his famous “Young heroes”, portraits of young Finns, tattooed; pierced; drunk; at heavy metal concerts or not, with the typical physical vestiges of violent fights. Short lives “lost in translation” amidst the profound financial and structural crisis that Finland experienced in the 90s: capturing the excess –or the vitality– of youth.

Following the thread of the artist’s life, the next room displays a series where the subject shifts from the person to the place, a dramatic shift, the result of a major setback in his private life (his step son is found dead of an overdose – in the late 90s – in a doorway in Helsinki). The end of excess, death. Lehtola stops capturing people, incapable of using the subjects as objects, taking photographs of the places where this need for life reaches its maximum levels, in a moment of searching and bewilderment. Images of spaces where one can almost hear the syringes as they tumble down the stairways; doors slowly closing. Places where this last wave of junkies left their lives, in their majority, well-heeled children searching for something more, in a place where alcoholism is a taboo, a scourge and personal relationships are frugal.

In a third stage, when Lehtola had access to the archives of the Finnish police, absence and death sharpen his shift from the space to the object. People return to the photographs, but in the image of a piece of data, a police archive, their faces always covered by their clothes. The objects with which they have met their death also appear: knives of all types; crashed cars; stones; various objects re-signified in their quality as lethal weapons. So much intensity for such a small space; perhaps it’s still strange for me to confront death so zealously, without it being normal.

At another time I would have labelled this display as taking advantage, easy, overly emotive (I say this for beginning with crying over the death of Lehtola). Without any doubt, we could question this intrusion and biographical suggestion given the power of the work itself. However, the quality of the photographs and the profound anthropological value, almost costumbrist, that pays incalculable witness to the specific rhythm and colour of a country, of an era, I’m gripped by this fervent confrontation of death, in work, in life –and after it. A sensation, that maybe isn’t, or maybe is, due to the merits of the Kiasma.

Marina spent the first two years of her life without saying anything: they told her parents that she was internalizing. And even though it’s a while now since she learnt to talk, she still needs to internalize. To then shake things up, question, order, disorder and celebrate. She finds politics in many places and has a special interest in all that’s subaltern, in the “commons”, and in the points where all this has an impact on creative expression.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)