Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

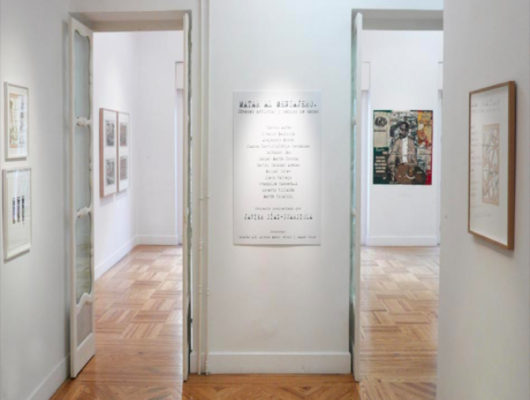

“Matar al mensajero. Jóvenes artistas y medios de masas” (Kill the messenger. Young artists and the mass media) is an exhibition, curated by the journalist Javier Diaz Guardiola, that can be seen at the Fernando Pradilla gallery. The show aims to reflect on how young artists perceive and represent the mass media in their work and how on many occasions they make avail of them as the support with which to question their contents. The curator starts with the general supposition that the mass media manipulate the collective perception, thereby creating a false, shared reality, far removed from any principle of “truth”.

In order to back up his discourse, Diaz Guardiola recurs to two basic, unwritten, laws of journalism that today if not obsolete are superficial. The first of these “laws” is the infamous, “if a dog bites a man it’s not news. But it is if the man bites the dog”. What is certain is that the reality is another, as the mass media have no other task than to communicate constantly, even if nothing happens. As J. Baudrillard would say we live in an ecstasy of communication, in a state of hyper-information and hyper-visibility, which frequently provokes a saturation of banal news that interests nobody, but which produces noise and covers up what should stand out. We endure it every summer, the season when the world seems to become paralysed and the media report on the holidays of politicians, football players or the monarchy, or the dangers of exposing oneself to the sun. An ecstasy of communication that has no other raison d’être than feeding the machine that produces contents for distribution across the networks, that far from creating opinion are consumed with total indifference.

The second rule that Guardiola indicates is, “Don’t let reality destroy a good headline”. We live face to face with a mediatized reality, constructed out of symbols and fictions, one that is impossible to access through our own experience, as all the events pass through the filters of the mass media. That the media manipulate us, though not an entirely false statement, ends up being simplistic in its approach, as it stems from the supposition that the media know what reality is, when though it is true the media influence, in turn they are also influenced. As the philosopher Daniel Innerarity observes, the media don’t manipulate so much as construct the scenario that ends up being possible. More than manipulating, what the mass media do is impose the subjects of reference, that is to say, they tell us what issues we should have opinions about.

The majority of the artists selected reflect on how the traditional media, newspapers and television, manipulate news and create parallel fictions, that is to say, the same resources as used by artists. Ignacio Bautista (Madrid, 1982), in his series Paper view, intervenes, with pastels, on the pages of a newspaper, eliminating the political figures and leaving only the scenario from where they exercise their power. Alejandro Bombin (Madrid, 1985) reproduces to the millimetre covers of newspapers and magazines. Francoise Vanneraud (Nantes, 1984) in Cada día en superficie es un día bueno suppresses the bad news in a newspaper, so that the pages end up without any content, totally white, where one can only see advertisements and news of marvellous frivolity. Salvador Diaz (México, 1977) also intervenes on the pages of a newspaper, eliminating here, underlining there, to impose his own personal reading. In the same way, Carlos Salazar (Bogotá, 1973) uses the covers of various newspapers, decontextualizing the images to give them greater prominence than the headlines. Lastly, Carlos Aires (Ronda, 1974) in his series Long Play uses photographs, extracted from the ABC newspaper archive and decontextualizes them, changing their meaning by inscribing on top of them the titles of different pop songs, in gold letters in a gothic typeface.

Along with the printed media, newspapers and magazines, television is the other medium critiqued in this exhibition. Daniel Martín Corona (Madrid, 1980), in his series …3, 2,1 schematizes in a few lines the resources employed by the majority of television news programmes to create their sets: the table, the logo, the info-graphics and the theme tune. True Box is the projection by Miguel Soler (Seville, 1975), where hanging in the space, a box slowly revolves, on each side of which appear different logos from a variety of mass media, and though they are different, they all end up looking the same.

What’s surprising is that though they are young artists, it is the traditional media that dominate, principally printed newspapers, and that there is no reflection on any other type of media that has modified the world of communication, such as the Internet or social networks. The exhibition, ultimately, ends up being reductionist in its approach and in the development of its investigation of the subject. The only thread running through the exhibition is a “suspicion” of the media, that though partly justified doesn’t explore in any depth what it means, nor any of the other relevant aspects that dominate the current discourse about communication.

Rosa Naharro endeavours to think about the present, considering its distinct contexts, through culture and contemporary art. Looking at exhibitions, writing, reading, film, music and even conversations with friends serve as her tools. Understanding and interpreting “something” of what we call the world becomes a self-obligation, as well as taking a certain stance, that doesn´t distance her from it. She combines writing for A*Desk with writing her doctoral thesis at the UCM and working with cultural management projects.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)