Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

How beautiful are the women in the picture?[1] And how many faults do they have? These two American influencers don’t represent the ideal standard of beauty, and yet they have thousands of followers who admire them for not having subjected their bodies to plastic surgery.

The standard of contemporary beauty is fitness: being healthy and exercising. Slimness sells; sculpted bodies are more aspirational and desired than fat bodies. Overweight is considered an illness suffered by people who are lazy, unkempt or have little self-esteem (although this isn’t always the case), to be treated by joining a gym or undergoing surgery. Nobody wants such an agonising life for oneself, a life in which everything around you, people and objects alike, remind you that you don’t fit in. Our society tends to be lipophobic, i.e., it is terrified by fat, hence it is also fat phobic. We don’t want to be fat or to be surrounded by fat people because they tend to make us dismiss them. Yet this contradictory, as although living a healthy life is encouraged, the population is getting fatter by the day, as proved by studies of overweight and obesity: in Spain, over 20% of children are overweight,[2] and the figure among adults is almost 40% around the world.[3] This situation is caused by bad diets, stress and low incomes.

What sort of society promotes a canon that is totally opposed to the evolution of its inhabitants? As Gilles Lipovetsky notes in his book entitled Hypermodern Times,[4] our context is that of ‘hypermodernity’, made up of individuals who are increasingly anxious, who want more and evermore quickly, who are technologically stupefied, global, individualistic and narcissistic. We’re all a mixture of these attributes and move following the dictates of the mass, as Byung-Chul Han points out in The Expulsion of the Other.[5] The other is increasingly less accepted; those who don’t share our tastes are perceived as undesirable and consequently rejected. According to Han, we are sick of ourselves, sick of seeing extensions of our personality everywhere, of aspiring to be the same as others, and for them to be the same as us. That ‘something new’ that others and their differences provide us with is lost in favour of homogeneity. This is how this author defines our relationships on social media.

A severe aesthetic canon oriented towards fitness, an increasingly anxious society and a more homogeneous social corpus produce individuals who, compressed by these three spheres, feel imperfect, flawed, judged and unhappy, and who are also increasingly less pervious.

Fashion plays a key role in the shaping of our personalities and of our social function within our communities, yet today this role is perverse, causing physical frustration, separating people in economic terms according to population sectors and class, and creating and destroying many of our desires. This is due to several reasons. In the first place, fashion is the sector that imposes the most absurd and changing aesthetic norms, keeping the wheel of consumerism moving. As a result, new garments are continuously entering our wardrobes, whether we need them or not, because buying gives us a false sense of happiness inspired by the idea of following the latest trends. Little importance is given to the amount of pollution added to the planet when items of clothing are bought, or to the subhuman living conditions of those who have made them. Those who confection a simple T-shirt in overcrowded workshops manufacturing clothes that may take around half an hour at the most are usually paid roughly € 0.50 (at a rate of € 1 the hour). If we bear in mind that large fashion chain stores sell T-shirts at € 3, € 4 or € 5 each (which involves the manufacturing of the fabric, the cut of the garment, the pressing, the dye sublimation print process in the case of them including images, the labelling and the companies’ profits), a dressmaker’s salary is absurdly low. In fact, the salaries for jobs throughout the fashion production process are negligible — otherwise it wouldn’t be such a profitable sector. We’ve devalued clothes to such an extent that we’re unable to appreciate the effort entailed by placing a garment on the market and the number of different agents involved in the process. Secondly, we come across the issue of sizes. The sizes offered by the market don’t fit all bodies. The European sizing system is the result of a proportional balance between the measurements of breasts, waists and hips. Unfortunately, the reference is still Marilyn Monroe’s 90-60-90, although if we look at countries like China or the USA, for instance, the situation is very different. The average woman in that Asian country has small breasts, narrow hips and is short, whereas women in the huge American country have more curves.

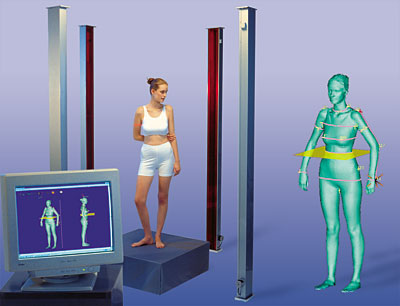

Today, the measurements for a size 38, the standard in our system, are usually 88-70-94, though few women have those proportions. The peculiarities of each individual body aren’t contemplated here, which is why we often have to buy different sizes for the same type of garment. There are two tendencies when it comes to solving this problem. On the one hand, sizes can be standardised by the addition of intermediate sizes. Normally, the difference between one size and the next is of two centimetres, i.e., the breast measurement for size 38 would be 88 cm and that of size 40 would be 90 cm. In my opinion, this isn’t a valid solution because it perpetuates the present system; companies will continue to produce their standardised measurements, albeit more fragmentarily, and the only difference will be that we shall begin to associate the volume of our body with one number or another. On the other hand, sizes can be customised.[6] Using a scanner, bodies are digitised in order to obtain personalised patterns and create clothes made to measure, thus avoiding the torture of industrial sizing. This is a brilliant solution but it doesn’t respond to the infrastructure of today’s fashion. Customisation is expensive, while standardisation covers a greater portion of the population and is therefore more profitable.

Thirdly, we discover the physical or virtual use of garments. Not all affordable brands come in large sizes, yet their manufacturers promote fat phobia. One such example is Violeta by Mango: a different physical space and different garments for people who wear large sizes. It’s a clear case of discrimination. If you’re fat, you can’t buy clothes in Mango shops, only in Violeta for Mango, which is the same although not quite. In this way, a usual Mango customer has no reason to feel offended when a fat girl buys the same dress she herself has bought. Another example is H&M, whose shops have a plus-size section that also have different garments. If your size is large you seem to be destined to wear a sack, a common complaint made by most girls who wear plus sizes.[7] A third example is Kiabi, a firm that placed its large sizes on the upper floor of their shop in the centre of Barcelona but was forced to rearrange the space as women didn’t go up to the top floor to buy clothes. When you enter a clothes shop you want to buy clothes, not feel marginalised. And the fourth example is Asos, a digital platform selling clothes in a range of sizes yet the website presents its plus sizes in a section called Curvy. So, we could ask ourselves what is the fashion industry doing to promote non-discrimination? Or even, what are designers doing creating sacks to hide the ‘faults’ of plus-size women instead of designing garments that actually suit them and make them look good?

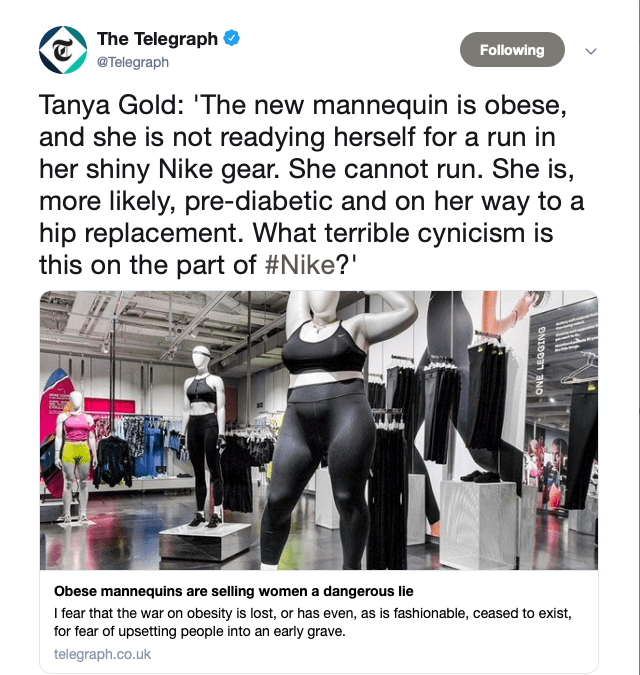

A fourth reason why fashion creates social disease is spectacle. In recent years, plus-size women have appeared on the catwalks, and curvy models like Ashley Graham wear size 44. Women whose breasts measure more than 95 cm (more than half the female population), whose hip size is over 100 cm or who wear a size larger than a 42 are considered curvy, yet size 44 clothes are the most sold.[8] So why is 38 the standard size? Putting plus-size women on catwalks is positive because it sheds light on our prejudices against people we consider fat. But in terms of real change, its effect is purely anecdotal. A number of initiatives have been set up to endorse this change, such as Body Positive, a movement promoted on social media by women who hope to break this barrier of fat phobia showing their nude bodies from a position of self-confidence and dignity, demanding respect. Besides giving rise to much criticism, the project has raised a new debate: is it a question of empowering women or of normalising overweight?

A few months ago, Nike placed a plus-size mannequin in one of its London shops, triggering an immediate outburst of fat-phobic comments on social media. Apparently, people who wear large sizes have no right to wear tops or leggings. In both cases the response is negative: if we empower women, we’re doing the wrong thing; if we normalise overweight, we’re doing something worse. We should reconsider the idea of body we have constructed. In this sense, fashion designer Rei Kawakubo created a collection entitled Lumps and Bumps in which she raised such issues, developing garments with bulges in order to project a sense of strangeness and make us reflect on the body as a dynamic figure that changes over the course of time and is subject to the whims of nature.

Finally, speaking as a fashion and pattern designer specialised in plus sizes, I am outraged by comments concerning parts of the body that fat people should conceal because they are considered to be shameful: the lower part of arms, knees and even cleavages. This is why plus-size patterns have their own characteristics: armholes that show no flabby skin, dresses of a minimum length that cover the knees, loose waists, etc. The freedom anyone has to dress as they like doesn’t apply here due to the moral obligation of a correct appearance in a society that doesn’t like wrinkled knees. It isn’t a personal decision but a decision imposed, and it ends up creating personal insecurities. The fact is that ever since we began to fight for our rights as women, we’ve overcome numerous aesthetic taboos such as body hair, for instance, which would have been inconceivable ten years ago. However, until we overcome the prejudices we’ve gradually taken for granted regarding our fellow women and our own bodies, fat phobia will continue to exist. Until we understand that each and every one of us is free to dress as she likes and to reveal what she likes, to feel proud of her belly or her knees without the rest of us having the right to look down on them, we shan’t be able to progress as a society. Nothing is more natural than time and, as it gradually slips away, we’ll all have wrinkled knees.

[1] Website image: https://www.womenshealthmag.com/es/noticias-deportivas-femeninas/a27100201/influencers-curvy-instagram-imagen-bikini-asos-body-positive/

[2] Data from https://www.revespcardiol.org/es-prevalencia-obesidad-infantil-juvenil-espana-articulo-S0300893212006409

[3] Data from the WHO website: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

[4] Gilles Lipovetsky, Hypermodern Times, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2005.

[5] Byung-Chul Han, The Expulsion of the Other: Society, Perception and Communication Today, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2018.

[6] Website image: https://www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/7060/3d-body-scanners-virtual-trials-for-real-comfort

[7] I recommend you visit the following links: https://www.abc.es/estilo/moda/abci-peticion-viral-inditex-para-aumente-tallas-favor-amancio-tengo-culo-grande-201804161832_noticia.html o https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/01/12/eps/1515778670_826006.html

[8] https://www.lavanguardia.com/de-moda/moda/20140804/54412745690/talla-44-mas-vendida-espana.html

Cristina Real Domínguez (1985) is a fashion designer, a plus-size pattern designer, a teacher of design and a curator of digital art. She has worked on fashion research-related projects with brands such as GoPro and Speedo and organisations like the University of Eindhoven (TU/e), IaaC and Intercolor. She is fascinated by everything connected with images, their manipulation and perception. In the field of fashion, her research focuses on methodologies of experimental pattern designing linked to generative design.

She is currently working on her Ph.D. in which she explores in depth the idea of taste and the aesthetic imaginary that shapes it.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)