Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The dictionary of the Royal Academy of Spanish (DRAE, for its initials in Spanish) provides two different definitions of the word impostura: the first is that of a false and malicious imputation; the second is that of a pretence or deception with the appearance of truth. If we look the word up in Google, the search engine tells us that there are approximately 1.470.000 results. Over the course of history and, more specifically, of the history of art of the past two centuries, the concept of imposture has provoked diametrically opposed visceral reactions. While some believe that given human impossibility to avoid pretence the best we can do is to accept it and assimilate it into our lives, others furiously defend a supposedly sacred truth.

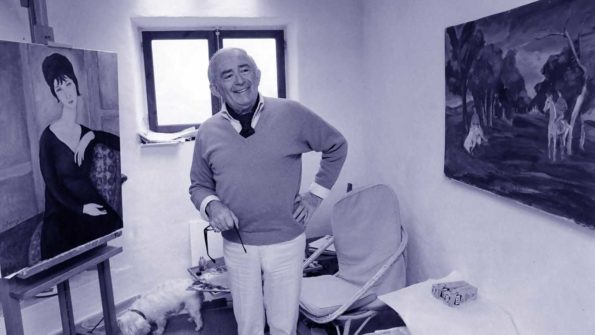

In September 1976 the television programme entitled A fondo broadcast an interview between Joaquín Soler Serrano and famous art forger Elmyr de Hory, about whom very little is known although much has been speculated. Hory was supposedly able to copy numerous styles to perfection: Picasso, Modigliani, Gauguin, Matisse, etc. However, he didn’t just make crude copies of existing pictures but actually appropriated the characteristic traits of individual painters, which he used to create works of his own. Or at least … or at least that’s what some theories tell us. Others, conversely, like the one upheld by his lawyer Rafael Perera, lead us to believe that Hory couldn’t really paint at all and that there was no studio in his home, that it was all a falsehood. In the interview conducted by Soler Serrano, a jovial and smiling Elmyr steers the course of the conversation and deftly changes the subject when the interviewer’s questions put him in a fix. He continuously qualifies the lies (or the truths?) told about him in numerous biographies and articles (official, apocryphal, authorised and unauthorised) and goes on to quote Oscar Wilde (who else?), ‘There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.’ Everything he says could be untrue or could be true. Three months after that interview, Hory committed suicide taking an overdose of barbiturates at his home in Ibiza, desperate in the face of his imminent extradition to France, where he was accused of forgery and other crimes. Or at least, that’s the official version, because the view of Clifford Irving, one of his biographers, is that Elmyr took imposture to its ultimate consequences, feigning his suicide and subsequently fleeing to Australia. Where was the scandal, in his life or, as he himself declared, in the art market? Even though it may seem hard to believe, there are many stories like Elmyr’s and even more ways of understanding imposture. At the end of the day, perhaps it would be best to understand it as a form of appropriation of places, as Juan Echenoz told Enrique Vila-Matas. Perhaps artists and impostors are those who show us that reality is merely trompe-l’oeil. Maybe imposture is the best field in which to shake up the academic inertia of pre-established identities. It may even be present everywhere, whether we’re aware of it or not. All these are theories that will be developed by our contributors this month. Turning to different literary genres (from narrative texts to those that are more essay-like or even autobiographical), David Santaeulària, Anna María Iglesia, Nicolás Koralsky, Víctor Balcells and Gisela Chillida will explore the history, applications, uses and abuses of imposture in contemporary society.

After reading them, all that’s left is for us to invoke the spirit of Gaspard Winckler, the leading character in Portrait of a Man[1] who, fed up with working as an art forger and tormented by the impossibility of making a perfect copy of Antonello da Messina’s Il Condottiere, brutally murders Anatole Madera, who had commissioned the forgery. Just to tell him that it wasn’t perhaps worthwhile to torment himself so much as, to quote Agustín Fernández Mallo, ‘the value of a copy is precisely what distinguishes it from the original and at the same time is identical to it.’[2]

[1] Georges Perec, Portrait of a Man, translated by David Bellos, MacLehose Press, London, 2013.

[2] Agustín Fernández Mallo, Teoría general de la basura, Galaxia Gutenberg, Barcelona, 2018, p. 60.

It’s hard for Marla Jacarilla to define herself, though she’s been obstinately trying to, since a few years ago they told her it would be good for her to have an artist’s statement. She makes art (or at least tries to) she writes about film and every now and again reflects on things that usually pass unnoticed. Somehow or other this all comes down to one thing: an obsession for the letters that form words, that then form sentences, that form paragraphs, that form chapters that tell us stories.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)