Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Virality has been at the heart of the debate about social media for some years now. Who doesn’t want to create content that spreads uncontrollably, like a virus? To receive both economic and social revenue, in the twinkling of an app. I write, however, at a time in which virality has taken a different turn. May 2020, still in the midst of the lockdown derived from the Coronavirus pandemic. The collapse caught us all by surprise. In a flash, a chain of events was unleashed. That patina of success virality had, husked and saw itself covered again by the shadows of apocalypse that had historically accompanied it.

Up until recently, days went by slowly and months went by quickly. Always being alone in the same place, sitting down at the same table, my perception of time is different and everchanging. Now, days seem to fly away, at least from me. I keep on writing, but my anxiety to reach certain dates and to achieve certain goals has been disappearing. My concentration and productive capacities have slowly decreased throughout the lockdown weeks. However, my need of being connected, which seems to be the only way of maintaining certain balance, hasn’t.

As the world slowed down, the exchange of data accelerated even more. Every single platform has taken action to create content and keep our attention with resources to fill our time with. Simultaneously, every company capable of doing so, has taken action to expand their digital and remote infrastructure. The information flow is massive. Everybody is connected, and we reply to both calls and messages almost instantly. I’m only at home, but I constantly look at my mobile and computer screens. It’s actually nothing new, but now the connection between my state of mind and my social interactions has an ever more tangible presence. Maybe the world has somehow stopped, but its digitalisation process, that was already vertiginously fast, has radically accelerated.

Digital communication imposes a frenetic, massive and constant information flow exchange that has only increased during the lockdown. That must be taken as an object of great concern because behind the social media software, there is social and emotional engineering. Geert Lovink analyses in his book Sad by Design, how the design of social media generates sadness. In the digital social sphere, we can only be alive by being present. Likes, followers, replies to our comments or messages are the only proof of our existence in that world. To avoid feeling ignored or worthless, participation becomes compulsive. We become addicts to the dopamine each social exchange generates. Between exchange and exchange, the anxiety of waiting appears, along with boredom, feeling undervalued or worthless… And with all this, sadness. What effect will the fall of social activity after lockdowns are lifted have in our state of mind? What effect does the increase of said activity have in the social fabric?

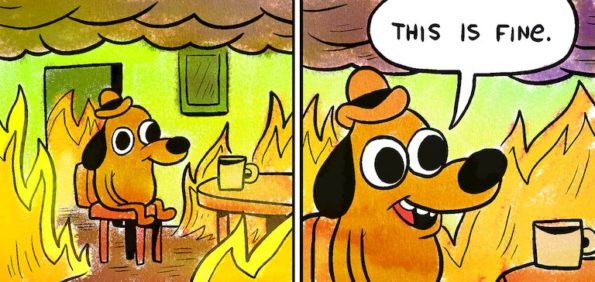

The Web 2.0 has brought new forms of interacting and creating community with it. Little by little, the Internet has been organised around social networks, and, therefore, based on participatory dynamics managed by invisible software operations. Just as these networks are built, individuals see themselves segregated in communities that take form of congregations. We follow profiles, groups, publications that align with our preferences and beliefs. Spaces that we share with other people with similar opinions. Simultaneously, we block notifications from those that don’t, or we simply cancel the friendship. We are isolated in groups of interest and opinion that favour the strengthening and radicalisation of beliefs shared by their members through the projection of otherness. In this context, what’s social leads to what’s viral, and memetic things acquire an evangelic role in which humour plays a main role.

In this context Lol is born. A formula condensed in only three letters, a way of laughing that has a lot to do with trolling. The Lol encapsulates a certain mockery within itself. Internet culture has been organised around an ironic form that claims to be irrelevant in itself. Things are done merely for the lols, making it possible to justify like that almost any type of comment or attitude. This irony seems to prevent us from building a consensus of truth or shared belief, but it is obvious that is not real. We all belong to groups of WhatsApp or Facebook, follow Instagram accounts or Tumblr ones (when people still used it) in which the content that brings us together through the mockery of certain things is uploaded. We, their members, laugh out loud and reply with likes. It’s precisely this consensus what gives unity to the group, and therefore, it’s what the lol is built around.

Faced with the omnipresence humour-based forms of language in digital conversations, this editorial was born with the intention of looking beyond mockery and segregation. To ask ourselves if lol contains other powers capable of, for instance, creating community. Does it only have a negative form, or does it also contain an emancipatory force? If reality is that we don’t laugh out loud, and that sometimes we don’t even laugh, what type of empathy is generated? Is it possible that it’s still capable of generating other forms of community or of laughing together? Being popular language, is it, maybe, a struggle through language to confront sadness?

Sabina Urraca reflects on how lol gives name to a laugh that doesn’t need to exist, and that, does indeed, divide us. In this information frenzy in which bodies are no longer together, laughter can’t be contagious and create that unexpected and momentary union between those who laugh. It only seems to be able to emphasise the divisions that were already there.

Anónimo García wonders about the lol’s emancipatory force as popular language. He starts talking about the rupture the Internet has brought, regarding the vertical communication imposed by the traditional media. The lol aesthetic, in the hands of users, competes against the previous “empire of the symbols”.

Daniël de Zeeuw worries about the subversive force of laughter in present times in his analysis. Along with Bakhtin, he reflects about the satirical representations figures like Trump make of themselves, and about our ability to deactivate them. If their own parody is already staged, what power does satire have?

Alicia Adarve claims the preservation of digital products such as the memes. She emphasizes the ability this form of humour has, despite everything, to be a testimony of its own time. Therefore, the possibilities of analysis it offers for the society that generates it.

Virginia Lázaro Villa, lives in London, she is an artist and art critic and what she’s most interested in is iconoclasm and the destruction of things in general. She’s co-directed since 2015 the contemporary art magazine and platform Nosotros and for a while now has worked writing for different media and magazines, as well as doing a few other odd jobs that bring in the real money.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)