Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

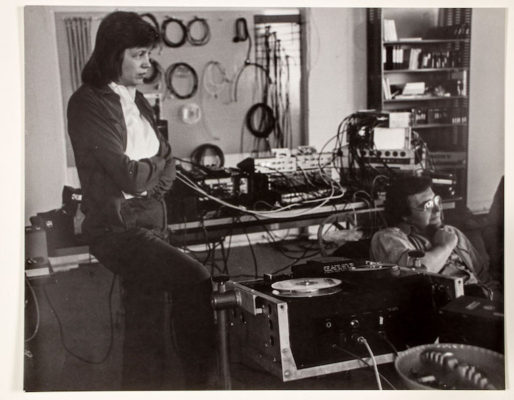

Photograph: Steina i Woody Vasulka

For over half a century, there have been uncountable artists who have explored the capacities of video. At the beginning of the sixties, pioneers like Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, Steina and Woody Vasulka, Joan Jonas or Peter Campus, amongst others, set off on their path. In a few years, the accessibility of new technologies and the appearance of video cameras like the Portapak marked a before and after in their working processes: they found new tools at their disposal and a broad horizon of possibilities that would end up influencing their work irreversibly. In its fifteenth anniversary, the Festival Loop takes a look back, making a revision of some of the works that have marked the origins of video art, configuring a sort of anthology of its origins that allows us via an analytical gaze to position ourselves at the present moment. During these months, Loop fills the institutions and galleries of Barcelona with video art, managing in this way to convert this past into an irrefutable present.

The conversations held between video-artists and curators within the framework of the festival, known as Loop Talks, have dealt with aspects that affect works of video-art, from the relation of the spectator with the space, the fragmentation of linearity through the use of multiple screens, the difference between film and television and the way in which the so called “new technologies” affect processes of production and/or reception of an art work as well as the different subjects tackled in video art since its beginnings.

Steina and Woody Vasulka were commissioned to begin this cycle. Pioneers of video art and founders of The Kitchen they deal in their projects with the relations between art, science and technology, developing a work that, according to the critic Don Foresta, “has a beginning, but no end”. A work, that evolves with the passing of time, and experiments with the materiality of the images themselves. Work not seen to be limited by the capacities of the technology, so much as one that untiringly explores them in search of its artistic potential. Through the intervention of analogue instruments, the Vasulka modify video and sound signals, create patterns and interfere with electromagnetic flux setting a precedent – already in the mid seventies – for those who would be artists of the so-called digital era. “By making art we became human”, says Don Foresta in a moment of the conversation. The phrase, of an overwhelming simplicity, makes me reflect. I observe with Steina and Woody, that they have a way of dialoguing that has a special complicity, one probably only achieved after many years of cohabitation and working together (in this case, more than fifty). Their training was very distinct (she as a violinist, he as an engineer), but it is this very diversity which enriches their work and which made a large number of artists converge in this interdisciplinary cultural space called The Kitchen artists eager to experiment, not just in video art but also with dance, music, sound art, and performance.

In the editing suite, when one advances or reverses the image, one learns something about the autonomy of the image. Like the slow camera of football transmissions, that have educated our gaze to discern the authentic fouls from those simulated, in the editing suite one learns to distinguish the effectiveness of images. (FAROCKI Harun, Desconfiar de las imágenes, Caja Negra Editora, Buenos Aires, 2013)

The beginnings of video art also brought along a series of fundamental changes in the relations that spectators establish with them in the environment in which they are exhibited. This was one of the main subjects during the conversations maintained with the artists Mary Lucier and Beryl Korot, What difference is there between proposing a work with a mono-channel video and doing an installation of various channels? How do the formal decisions interfere in the final result? The work done with the editing, the rhythm and the repetition, the fragmentation of a narrative that stops being linear and becomes kaleidoscopic, the passing from black and white to colour… Lucier talks of mono-channel videos as interior journeys and installations as places, she compares videos in black and white with charcoal drawings and colour video with painting, she reflects upon how the landscape determines culture and how culture configures the landscape, how art approaches both with the aim to reflect upon them. She asks if to produce images is currently one of the simplest things to do, how does this affect the way we perceive or assimilate them.

On the other hand, Korot relates the use of multi-screen installations with the transmission of information throughout history. At that point the inevitable questions arises: is the linear narrative a construct far more distant from reality than an installation that provokes a constant displacement of attention and the gaze of the spectator? Yes, probably. Korot, at the beginning of the 70s, was co-editor of the magazine Radical Software, the first publication that began to talk about video art and the use of new technologies applied to artistic processes. In Dachau1974 (one of her first multi-channel installations), for example, the artist confronts the spectator with images of the well-known concentration camp, a place that in 1965 is frequented by innumerable tourists anxious to photograph it converting the memory of horror into a souvenir.

At the beginning of the seventies, many of the artists dealing with new technologies, and specifically video, deposited a large part of their attention and expectations on television. Although they are considered multidisciplinary artists, Antoni Muntadas as much as Chip Lord (member of the collective Ant Farm from 1968 until 1978) used television to develop several of their pieces. In the conversations held, on the one hand, between Muntadas and Niels Van Tomme, and on the other, between Lord and Steve Seid, subjects discussed were; the power of the mass media and advertising, television as a domestic object, working with collectives, the active participation of the spectator in the work and the concept of happening, all the work in progress that evolves with the passing of the years, enriched by the interpretations of the public. Lord also talked about architecture in relation to art, the concept of re-enactment and a certain notion of utopia very much alive at the end of the sixties, a context in which political and student movements were very present and influenced artistic processes.

Finally, the last of the conversations was that maintained between Menene Gras and Jin-suk Suh, director of the Nam June Paik Art Center in Seoul. As well as talking about the tasks of conservation, dissemination and education realised by this centre, they discussed subjects related to the conservation of analogue works, copyright, the meaning of the image in movement in the present or the roles that a publically funded cultural institution has to fulfil. Subjects that half a century after the emergence of video art are still irrefutably relevant.

It’s hard for Marla Jacarilla to define herself, though she’s been obstinately trying to, since a few years ago they told her it would be good for her to have an artist’s statement. She makes art (or at least tries to) she writes about film and every now and again reflects on things that usually pass unnoticed. Somehow or other this all comes down to one thing: an obsession for the letters that form words, that then form sentences, that form paragraphs, that form chapters that tell us stories.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)