Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In Miralda Madeinusa, the autumn exhibition that MACBA dedicates to Antoni Miralda abounds in documentation, its display and the desire to lend form to its storage. The American archive of the Catalan artist occupies the rooms and acquires value as a protagonist. The show is an extraordinary opportunity to traverse his trajectory, but it’s more a recognition of what has been made, than an occasion for interactions and disturbances, paradoxically one of the constants in Miralda’s research. With the menu presented, I’ll begin with the starters (the pieces housed in the Meier building), although the best is concentrated in the main dish (Santa Comida in la Capella).

Works made in the United States, from 1972 up until the start of the decade of the nineties are exhibited on the second floor of the museum. The scope of this “inventory” is fundamental, but no proposals are indicated to update the projects exhibited. In all the compilation, the pursuit of accumulation and testimony doesn’t renew the archive from which they stem. Nevertheless, what is undeniable is the curator’s clear venture to highlight a very specific period. Through the selection and montage of the testimonial material, he achieves the objective of making known the projects carried out in Miami, Kansas and New York. Moreover it demonstrates Miralda’s prowess: the realisation of his works has always involved different social agents. Curiously the role of the public in Miralda Madeinusa is that of a passive receiver: the artist’s return home places at our disposition a strictly documentary menu. Now, only through contemplation, can we be accomplices in the revision of works that had as their leitmotif the generation of situations. .

The exhibitions Sangria 228 Weast B’Way, Movable Feast and Bigfish Mayaimi, Texas TV Dinner, amongst others, are, at the same time an homage and worthy applause for the successes achieved, a fossilisation of the participatory actions that Miralda deployed. An open archive? Yes, but, where does that leave the invitation to become involved and the incitement to break frontiers, so present in the artistic practice of Miralda? Probably one of the difficulties of exhibiting different registers or works already realised is that only the mise en scene of the recompilation is considered prime, and the formalisation of a new production or the reactivation of an existing work is not considered. Is it pertinent to generate reproductions to account for compiled and attested works? The recreation of Breadline (1977) is a success, unlike the recuperation of the scene and the bar of the L’Internacional Tapas Bar & Restaurant.

Is the production of new work not contemplated within the exhibition paradigms of a retrospective? If we only bear in mind the meticulous task of abridging and ordering the rich and profuse archive of Antoni Miralda, the proposal is compelling because it displays the different colours of the political, social, and economic landscapes in which the artist intervened with the comestible as a main axis. Nevertheless, a venture to re-signify these pieces through the present would have favoured even more the reinsertion of these works in the museum, as protagonists and witnesses of an era of which there is little or nothing left. The question remains: how to document the experience without fossilising it?

Does the link between the Statue of Liberty of New York and the monument to Colon, in Barcelona, suffice as an example of one of the representative pieces of this anthological exhibition. To remember a wedding thirty years later is an act of nostalgia and reveals how the passing of time transforms the love affair if it doesn’t end, converting into fetishes certain elements of the celebratory ritual of the union. What resulted paradoxical or even amusing beforehand, could currently be understood as twee and anachronistic. But irony and kitsch are good allies for the gaze. According to [[Néstor García Canclini, “Honeymoon: la fiesta como geopolítica”,in the catalogue Miralda Madeinusa, MACBA, 2016.]], Miralda’s monumentalization doesn’t encourage the toppling of statues but yes the development of logic that transforms the solemnity of an unaccommodating party, as it unites antagonistic emblems: American liberty and the European conqueror. Another resource to work with the intercultural element and its alliances.

One would also have to ask if one could do today what in the past was seen by some as irreverent. Honeymoon Project materialised over six years (1986-1992), a point one has to bear in mind in the current context, where the precariousness of budgets for works leads to their designed with a comparable elasticity. Neither can one disregard the profusion of de-colonialist studies: of celebrating in our times a party that reunites the great American family with the Spanish one, it would have to be less amnesic and heteronormative. Why not celebrate the silver wedding anniversary? Why didn’t Miralda generate an allusion to this, or to some of the other actions?

In all the revisions and texts written in relation to the work of Miralda there is a point in common: the majority of the critics accentuate the value of the participatory language developed by the artist. This aspect is missing in the first part of Madeinusa, where the explicit invitation for the public to become an active agent is missing. That said, active participation in the party reappears in La Capella, where a very tasty morsel is served: Santa Comida, a magnificent altar with naked flames.

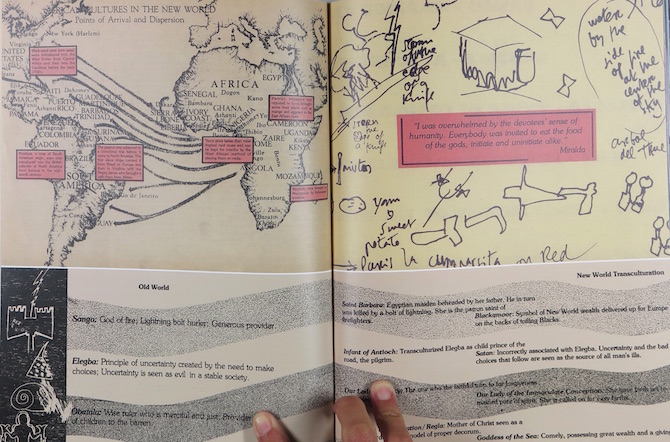

It is widely known that the subversive potential of knowledge, expressed in Santería, attracted Antoni Miralda, opening up for him doors onto a new world. The otherness allowed him to sublimate, through the representations of the saints and food that they offer, a type of knowledge not anchored in rationality, so much as one that stems from sensibilities, beliefs and sensations. To grant corporality and visibility to the phenomenon of Yoruba-Christian syncretism, and to dedicate seven altars to the better-known divinities of the Orishas, certify the Catalan artist’s ability to identify popular manifestations and transport them to the terrain of art, where, still today, there is a need to vindicate identities and difference.

This force is palpable as soon as you pass through the curtain that leads into the venue. The installation, an impeccable site-specific, is presented as the most complete to this date, that incorporates the large tapestry concocted with African fabrics presented at the Expo 2000 in Hannover. Undoubtedly the most important thing is that even though this large work forms part of the MACBA collection and can be considered a classic, it’s alive and invites participation. The piece manages to evoke and fuel rituality while also representing, not just through the figures but also through the odours, music and offerings, a certain aura motivated by ritual. It promotes the flight of the materiality of the work, to return us for an instant to the magical sense that sparkles when we live an aesthetic experience, that is to say, a transformative one. Santa Comida is moreover a work in progress to the extent that the public has at their disposal a niche where they can leave gifts for the deities and above all because it generates the festive, the ritual, and the witchcraft so typical of the artist.

Miralda entrenches his works in MACBA. The exhibition device is revealed as a large showcase, all of Madeinusa revolves around a recuperation of the projects safeguarded in the archive, apart from Santa Comida and the replicas of some of the pieces. In short the exhibition can be understood as a large souvenir del made in America. A lot of bread, a main course (Santa Comida) and for dessert, a splendid catalogue.

An incurable onlooker, Aymara Arreaza R. uses walking around, reading, the criticism of displacement and questioning as her working tools. She is a hybrid of trades: expressing herself through writing, some of her own images, teaching as well as research projects that she backs up with the construction of more personal geographies. Since 2011 she directs www.rutadeautor.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)