Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Cities usually have a great symbolic value for their inhabitants. For a city, being a symbol implies accumulating semantic charge, observed and reproduced in the use of clichés, street names, festivities and cultural events, in advertising and institutional propaganda. The contrivance of a symbol is the illusion of the ordinary, the idea that it may interact with specific experiences and preserve a meaning.

Brands exploit this semantic charge and translate it into the presumed universality of commercial value, with the common denominator of currency. They extract this symbolic energy through the notion of private property, living on revenue and accumulating power in an ongoing effort to redefine the terms of the social contract in their favour. A paradigmatic example of these dynamics is the reviled ‘Barcelona Model’, plainly described by anthropologist Marc Dalmau as ‘the strategic alliance between the state and the private sector to sell cities and their image (their brand), attract multinational investment and guarantee capital accumulation.’[1]

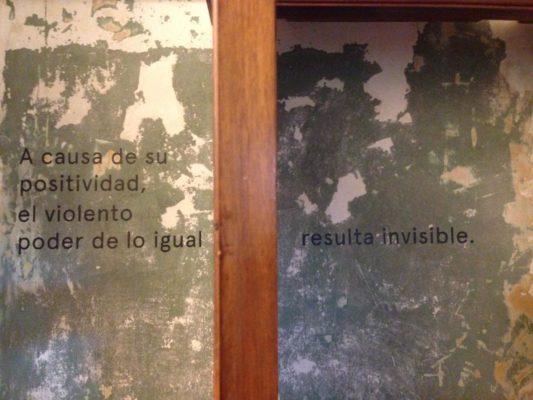

Like brands, models also promise a certain degree of universality, at least as regards their effects. The Barcelona Model is based on the city’s peculiarities, yet its ambition to attract capital has a global horizon. The result is the progressive homogenisation of the urban environment that eventually becomes visible in the proliferation of chain stores. A Starbucks or a Burger King on each corner, a 365 or a Pans & Company if you prefer to pay a little less or benefit a more ‘local’ company. When it lands, capital tries to avoid or dissolve the administrative barriers that alter its circulation, even if borders, walls and scars thrive in its wake.

Perhaps global capital’s aversion towards administrative borders is what has prompted Jordi Borja – one of the most outstanding exponents of the Barcelona Model – to propose that we approach the new urban dynamics starting from a metropolitan model of governance that operates beyond the borders between towns. ‘Barcelona projects us further, towards Spain, Europe and the world,’ wrote the geographer and urban planner in an article entitled ‘Ciudad metropolitana y plurimunicipal’, in which he suggests that the Metropolitan Region of Barcelona be ‘a field of action of the Catalan government and of coordination, cooperation and contraction with local governments.’ He also suggests that, from the point of view of the city, the Metropolitan Area be a space of reference to integrate, govern and guarantee the quality of basic services, public transport, housing and town planning programmes, sustainability and economic activity both in the central city and in its peripheral towns.

But the model is one thing and reality is quite another; the former is institutional architecture, and the latter is the anarchy of the real. From the perspective of capital, the central city in this model of metropolitan governance is a uniform entity. In this sense, what breaks the contiguity between Barcelona and L’Hospitalet is a sort of administrative irrationality. And the truth is that the physical border that separates L’Hospitalet de Llobregat from Barcelona is narrow. Quoting Paco Candel, journalist Gerardo Santos – a specialist in sub-worlds, crime reports and a variety of vampires – tells us how a handful of local anarcho-syndicalists, many of them originally from Aragon and Murcia who arrived in Catalonia in the twenties, placed a poster on Carrer de la Riera Blanca in La Torrassa neighbourhood announcing: Catalonia ends here. Murcia begins here. “’Nowadays,’ says Santos, ‘the only thing that proves the existence of a border on Riera Blanca is that on one side the message on the waste containers reads ‘LH spick and span’ and, on the other, ‘Barcelona City Council’.

This isn’t quite true. The constructed environment is beginning to change in Badal. Streets and buildings are getting narrower, façade are growing darker. But if there’s a place where a relatively thick border still exists that’s in the price of housing. The fact is that, historically, L’Hospi has been more a symbol for its inhabitants than a brand for capital, and yet as the Barcelona Model progresses we see how the Barcelona Effect is exerting its influence on the second largest Catalan city. Shortly before the property bubble burst, in an interview published in El Periódico, the then mayor Celestino Corbacho declared ‘In the past, we knew when we were leaving Barcelona, where everything was developed. When we reached undeveloped areas, waste grounds, we knew we were entering L’Hospitalet. But that difference is disappearing.’

Illustrative superficiality. Since2017, the Barcelona Beer Festival has been held at La Farga de L’Hospitalet. The geographical confusion in the name of the festival reflects the logistics of the metropolitan city and its infrastructure rather than the municipal administration. Barcelona isn’t only Barcelona — it’s also Zone 1 of the city’s public transport network (TMB). We feel tempted to attribute this to the imposition of the Barcelona brand, until we realise that the official sponsors of the event are the Catalan government and L’Hospitalet Experience, a semi-public, semi-private cultural and culinary initiative whose website states as follows:

Experience the effervescence of our cultural activities — from our cool djs to our traditional folklore. Picture factories inhabited by cutting-edge artists and music schools. Discover street art visiting top level metropolitan galleries and exhibition halls dedicated to both acclaimed and emerging artists of international renown. Ours is a genuine, unique offer. Come and see us. L’Hospitalet will surprise you.

The openness of the proposal is striking, as if the urbanity were its only raison d’être. In fact, the specific reference to L’Hospitalet could be applied to any other city in the global north and it would mean the same. This openness is a defining trait of L’Hospitalet Cultural District, the strategic urban project in which the initiative is set to promote the role of the cultural or ‘creative’ sector within cultural economic development planning. In turn, as we have already pointed out, openness as a strategy for accumulating contents and meanings to stimulate economic growth is also a characteristic that defines brands.

Fortunately, the Cultural District is still in an almost embryonic stage. Rather than ‘a genuine, unique offer’ the website of the project conveys a sense of indefinition. This could be an opportunity for both the more institutionalised local arts sector and for more risky initiatives like Espai Hybris, a humble and idiosyncratic cultural space characterised by spontaneity, ‘avoiding the homogeneity, excessive calculation and commercialisation of cultural and economic circuits’. The political question is whether the interests of cultural workers will come into conflict with the interests of other city dwellers, as is often the case in the neo-liberal towns that have followed similar development models. In other words, the main question is whether the idea is to attract tourism of financial capital or promote the cultural life of the city and its inhabitants.

[1]Marc Dalmau i Torvà, ‘Can Batlló: de la degradación planificada a la construcción comunitaria,’ Quaderns-e de l’Institut Català d’Antropologia [online], no. 19 (1), 2014, pp. 143-159. Available at https://www.raco.cat/index.php/QuadernseICA/article/view/280277 [Accessed 17. 03. 19]

Carlos Delclós is a sociologist, a writer and a member of Roar Magazine editorial collective. He holds a Ph.D. in Political and Social Sciences from Pompeu Fabra University, and he researches social change and inequality in urban contexts through sociodemographic analyses and cultural theory. He is the author of Hope Is a Promise: From the Indignados to the Rise of Podemos in Spain (Zed, 2015), and has contributed articles to several scientific magazines, as well as in The New York Times, Frieze, Jacobin, Opendemocracy.net, Eldiario.es, Ara newspaper, Ctxt and Crític, among other publications.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)