Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Johanna Palmeyro (Joy) is a museologist, educator, creator, and activist. She is a government worker and co-coordinator of the Museology and Communities Area at the Casa de Ricardo Rojas Museum in Buenos Aires. As an activist and art educator, she is the first tentacle of Movimiento Justicia Museal (Museum Justice Movement), a project born a year ago and that reviews, blurs, slaps, and shakes up museums and rocks those of us who work within them.

Joy says the Movimiento Justicia Museal / Museal Justice Movement (MJM) is a balm for her, a space for her to say everything she can’t say within institutions. It is a place for rebellion and therapy, in different two directions, one public and one private. She feels her work its work deals with social justice, but also individual injustices suffered by cultural workers, especially within museums. MJM obeys the streets and disobeys the institutions.

Ana Andrés Cristóbal: You have been working full-time with MJM for a year. How has the city received it?

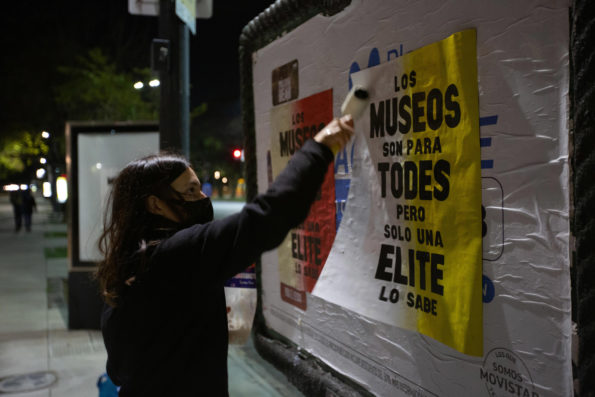

Johanna Palmeyro (Joy): The truth is that it has been received with a lot of love and a lot of hate. Its words provoke anger since I usually hit sensitive places. The work is displayed in the vicinity of the museums in order to create a dialogue with the institution. That’s what happened at the National Museum of Fine Arts with the first phrase: “Museums are for everyone but only an elite knows it,” a twist of a sentence by Dora García. I pasted it up and the next day I came back and it was torn. Two ladies passing by saw it and commented in front of me: “That’s bullshit.” That really amused me. However, it went viral when the Ministry of Culture shared the image, and many people have used it as a reference to decide how to confront and experience museums.

Ana Andrés Cristóbal: That first poster you speak of was born from the work of Dora García but also includes influences from the graphic work of Juan Carlos Romero and the disobedience of Liliana Maresca. However, something personal has been injected into the educational world. What other references influence your thinking and practice?

Joy: I am moved by a lot of disciplines that do not necessarily have anything to do with the art world. For example, the Zapatista Movement in Mexico, which invented a fictious leader because society always demands a leader, while, in fact, its structure is totally horizontal. Also, the Earth Workers Union. Their struggle is beautiful, and we should forge a culture-countryside alliance. I admire their struggle but also their way of organization. Their priority is to change the laws that allow access to the land, but beyond that there is a network of other struggles that focus on different laws. Marlene Wayar, a transvestite activist, is also a reference. She wrote Transvestite: A Good Enough Theory. It was clear to me that her message was what I understood as culture: to leave a space of privilege and inhabit other spaces. It reminds us that institutional culture is not necessarily real culture. She is currently the education coordinator at the Palais de Glace, here, in Buenos Aires, and I’m glad that she occupies a political space. Sussie Shock also comes from trans activism but within the language of music and poetry. She uses the languages of traditional Argentine folklore, which is clearly patriarchal, and she cross-dresses them. She’s spectacular. Identidad Marrón (Brown Identity) is a powerful collective of artists, activists, and lawyers who attack the structural racism of Argentina. They talk about building a brown identity. I find their struggle and their communication skills very inspiring. In the art world, I love how Jenny Holzer uses words. With just a phrase, a truism, a short phrase, she says so much. It’s beautiful how she can occupy a space with words.

Ana Andrés Cristóbal: It is interesting but difficult to try to situate you. You move on the border between the outside and the inside. Your work as a government employee brings the people to the garden/exhibition rooms while your own work inhabits the streets and questions institutions that often exist as marginal bubbles these days. Where do you see yourself in this complex intermediate space? To what extent is MJM also marginal?

Joy: It is difficult for me too to understand where I stand. I don’t really know. Before MJM, I was completely immersed in institutions, and completely convinced that public culture would change the world. Somehow, I still think this is true, although not so much from within the institution as from outside discourse, from groups that are born spontaneously in the streets and their conversations. This happens in public space and not in public institutions. The truth is I am interested in both. Without the institutions, MJM would not exist since its job is precisely to question them.

Ana Andrés Cristóbal: MJM starts on the internet, it goes out into the streets at night and is injected into the institutions afterwards. This project should generate certain frictions within museums due to its clear hacking of museum structures, and yet it desires to be integrated as part of the cultural production of national museums in Argentina. What do you think is the reason for this incorporation into cultural structures? Are you not worried about its possible appropriation? Where do you think it will head in the future?

Joy: I work for the government in the Museo Rojas, but my work as a creator in MJM is independent. It is my personal work and it has been difficult to process this within government structures. The posters grew out of the desire to be on the street. With MJM, I say what I want. That’s where the most powerful things come out, when I have no filter.

On the other hand, I can’t think of a future direction. The future is nebulous. I know how things are today. MJM lives in the present by addressing the present. It works to make visible and to activate reflection about museums. I also think of working to change the laws in order to change the working conditions of museum workers and the access of all people. I am also interested in taking it beyond Argentina. It’s a bit overwhelming because I don’t know how to do this beyond sharing posters and talking to others. I am not interested in hierarchies. It doesn’t have to be about me.

Ana Andrés Cristóbal: Your anti-patriarchal, decolonial, anti-racist, distributed and inclusive work questions the very foundations of our museums that make use of certain discourses but whose practice is undercut by historical inertia, pedagogies and invisible policies that limit, paralyze, and undo any real reckoning with their own words. I feel that MJM is like wake-up call. Do you think it really is possible to reform museums?

Joy: Museums will continue to exist. They were born to fulfill the interests of the bourgeoisie, to legitimize their goals. We can no longer follow the orders of these power elites of the past. We must stop thinking that the museum is only about the past and give way to new voices and narratives that are out there. Our job is to build bridges so that these voids and narratives can construct and reformulate our present. These voices, such as the Earth Workers Union, have taken over the garden.

Ana Andrés Cristóbal: Joy, is there anything else you would like to say?

Joy: MJM is from the street, even though I’m sitting in an institution. It belongs in public space. I fight against hierarchy and its structures. I don’t want to be the leader or the head of the octopus. I haven’t invented anything new, it’s all been happening in different places. I only create posters to make it visible. There are many people who are fighting for museum justice, I just want to be a tentacle.

Do it, own it.

Ana Andrés Cristóbal is an art educator and curator, but above all she works as a natural dyer and farmer. Although she has worked for a decade in “important” museums, she decided to go into self-exile in order to move to the countryside, which is where she believes real culture resides, looking to the past to make the present. She doesn’t believe too much in works of art, and believes that culture lives in the everyday things that allow us to live well.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)