Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

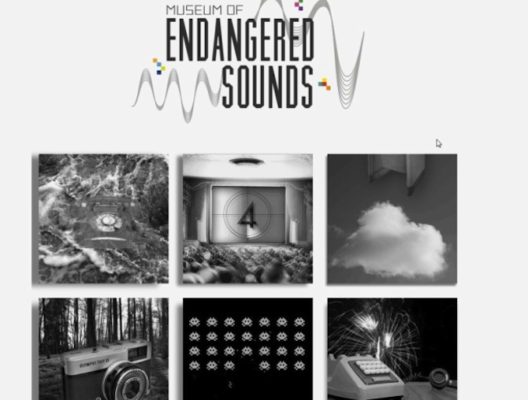

The Museum of endangered sounds is a project by Brendan Chilcutt. Launched in 2012, Chilcutt’s aim is to compile all of those sounds specific to the analogical world, that is, of old electronic devices. Chilcutt recreates these complex sounds in a language that reinterprets them as binary compositions. According to his explanation, the project ought to be complete in 2015, after 7 years of research endeavouring to reproduce faithfully the subtle but ever so characteristic sounds that have almost disappeared.

The sound of a VHS tape, being sucked into a video-player. The unmistakeable sound of a Gameboy, with its simple but pretty melody. The sound produced when cleaning a Nintendo cartridge before inserting it into its slot. Sounds that are slowly being lost, substituted for refined buzzes and the elegant movement of agile fingers across various different surfaces.

It’s worth remembering the sounds of our infancy. In fact many digital devices try to recreate these sounds. The strange whirr reproduced when sending an email, the sound of numbers turning when programming the alarm, as if winding the cogs. These sounds are reminiscent of the analogical world but aren’t. It maybe they’re necessary for those of us who aren’t of the digital generation, so that we really feel as if we are carrying out an action when clicking “send”, but they can’t substitute the true whirr or sound of working machinery.

The “Museum de Endangered Sounds” recuperates these sonorous delicacies, immortalizing them, ironically, in digital form. The supposed contradiction of creating a digital museum of analogical sounds might pass by unnoticed. In the eyes of our society digitalizing sounds is the most logical thing. It is the most obvious option. But it also reveals something fundamental: the analogical doesn’t have a place in our world. Can the digital rule as the only thing capable of representing the new reality of the world? Even those sounds that in their time were incapable of inhabiting another space that wasn’t physical, must now submit, transform and reconvert in order to be able to exist again, to prevail for the whole of eternity. Or until the format becomes obsolete. Whichever, comes first.

The project of Brendan Chilcutt is just another example of the identity crisis that the digital reality is provoking in contemporary culture. A crisis about which, art will have a lot to say.

Verónica Escobar Monsalve is a restless soul, with a digital nature and an analogue heart. Her investigations centre on art and culture that mix the digital world with pre-digital thought. Art and culture that is capable of reflecting the complexity of today’s world. She believes in the vital importance of a critical spirit and how this can be applied to any facet in life, however difficult it may be.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)