Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Everything exploded on the eleventh of September 2012. The thing had been brewing for months –or years, or scores of years—, but that day it all came together in a mass demonstration of a whole bunch of people, I’m not concerned with the exact figure, but there were a lot of us. I also won’t try to explain the motivations that led each one of the mobilised citizens to become that multitude, en masse. However, a percentage of the demonstrators were there to express a double indignation, I know because it was—is— my indignation and that of several others who’re tuned into this question.

On the one hand, an indignation with the political system or with the system tout court, that is to say, with the false democracy installed in Spain since the ever so sacrosanct and disastrous “transition”. A perverse form of functioning that facilitates, or forces the votes, deposited by the citizens in the majority of political parties—or in all the major parties— to be used to strengthen the financial system, consequently, augmenting social inequalities instead of fighting them. And this without any need to refer to the corruption, prevarications and general stupidities arising within the public echelons.

On the other hand, indignation at the ill treatment that Catalonia, the Catalans, and Catalan culture have been dealt by a large part of the political and media apparatus of Spain. At least, as far as I understand such concepts of Catalanism, devoid of fundamentalisms, and albeit that Catalan culture has always been peripheral, a hybrid, full of stimulating contagions, that absorb and are absorbed … for all that, its existence as a system in its own right cannot be denied. This system has been repeatedly attacked by the Spanish State, but in the last few years these attacks have reached extremes of totally irrational stupidity; against the Catalan language or with judicial or political decisions contravening what the people of Catalonia have expressed in their majority in elections or in a referendum convened in accord with current legal regulations.

After that demonstration, that outcry of indignation, there came the turbulent comings and goings of professional politics, all and sundry, of one colour or another, from here and there, sought to regain the prominence that the citizens had grasped from them: the particracy, the last remains of Rousseau’s “social pact”, the false division of powers. All things considered, based on that mobilization, Catalan society proposed a debate of a very high calibre: the need to exercise a basic democratic right, that of deciding if Catalans want to continue to pertain to Spain or whether they want to create a new State. Democracy in its most direct reading, where one citizen equals one vote, without the interventions of political parties. That the majority wins and the minority accepts it, like those democrats of us who for more than thirty years have lost and have accepted being a minority, minority and minority.

It doesn’t escape me the paradox of asking for a new State, for those of us who don’t hit it off with the repressive forces of States. I’d also like to mention Bakunin when he —perhaps apocalyptically—referred to States as the cemeteries where individual liberties are buried. But the internationalism of anarchist roots, in my understanding, has become something more utopian than a utopia, at least for the moment. And if we’re set to end up with a cemetery, what more ideal way than to choose it democratically?

A year after that first demonstration, faced with the commotion and uncertainty about which way to proceed with the process, it’s possible to propose a few reflections about where we are and where we could be in a few months time within the cultural register, above all, within the artistic register. The field is so open that I have preferred to focus on a few questions and suppositions that arise in the face of a initial verification: the generalised silence with which culture and art have followed all the political events of recent times. Perhaps I’m wrong, but I have the sensation that intellectuals and artists have barely intervened in the debate about the process, which has unfortunately been left in the hands of politicians, economists and journalists.

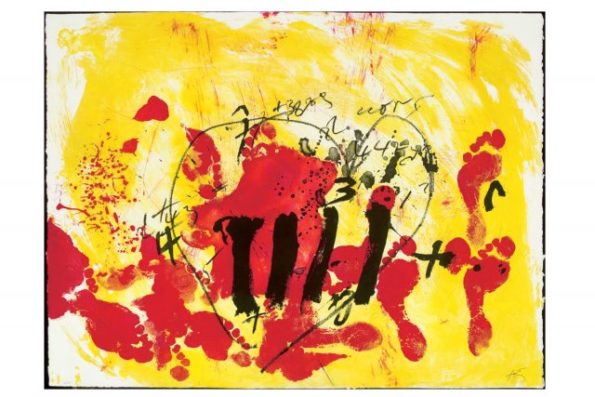

If my premise is valid, how does one explain this negligence, such a degree of insipidity? A while ago, the artist Albert Gusi made me come to a reflection that is worth sharing: in the “Concert per la llibertat”, celebrated on the 29 June 2013, in the Camp Nou, poetic and musical outcries were heard; a concentration of performances and participations coming from the most varied fields within the world of culture, but not one visual artist intervened. In other times, a backdrop painted by Miró or by Tàpies would perhaps have presided over the stage, but on this occasion the visual artists of the country that could have shared in the separatist substrate of that event didn’t participate in it. Why? Were they not called upon to participate? Did they not ask? Aren’t there any artists that want Catalonia to have its own State? Or, if they exist, have these artists not found the way to display a visual call for identity?

It’s true that the ways of expressing what some philosophers, between the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, called Volksgeist are eminently verbal. The spirit of the people, the idea that each nation has some characteristic cultural traits, comes determined above all by language and literature. There are also a few landscapes, symbols, a history, but the language—in Catalonia, but also in Spain, as we well know— is what predominates in the patron of identity. What is more in the era of globalization the case of the post-modern has expanded, where rather than specificity one has to prefer contagion and transference. In the time of cyberspace it seems that everything must inevitably tend towards a collective, global identity, to becoming citizens of the world, excluding any pertinence to specific communities (or identities). And all this without mentioning that the history of art demonstrates how interpretations of certain pieces made according to identity, often have more to do with a process of hermeneutics than with the traces that those pieces might really contain. In the exhibition “Joan Miró. The Ladder of the Escape”, one could see this, for example, in various, supposedly, “committed” pieces by Joan Miró.

Yes, we find ourselves in slippery terrain. However, despite these misunderstandings, it’s true that the call for identity is more difficult to express with images than with words, that is not to say that the visual is incapable of rebelling against this possible ontological “lack” that Diderot with great criteria referred to in some of his writings. Painting, sculpture, printmaking, photography, film, video and so many other languages of the visual sphere have expressed, or at least have suggested, universal, symbolic ideas, and haven’t limited themselves to capturing mimetically the external reality. What is more, in contemporary times, the work of art has dared to make profound metaphysical reflections and has been proverbially accompanied by a theoretical or critical counterpoint. Without going any further, Benjamin Buchloh has indicated that the abstraction of Gerhard Richter couldn’t be anything other than Germanic. Consequently, in this silence of the Catalan artists of today regarding the separatist process perhaps we have to find a –legitimate, on the other hand— lack of motivation?

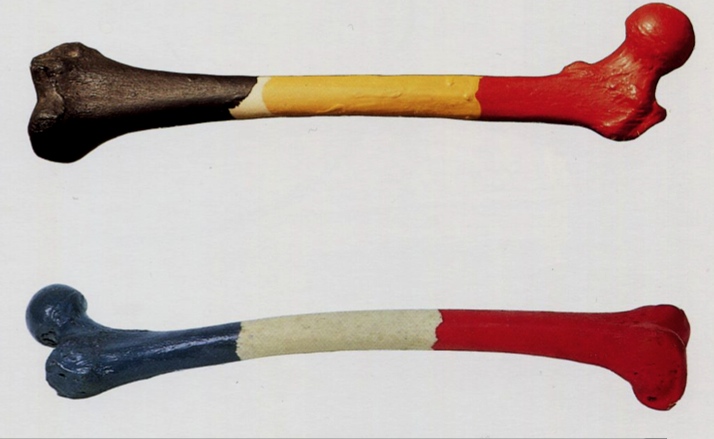

Are artists today that preoccupied with their adscription to a national community that situates them within a national art history? Do they want their works to enter into nearby museums (MACBA, to give an example) or do they aspire to entering into forming part of the stories about contemporaneity that the grand museums of reference are still formulating today? And yet another final question: How many international artists have been preoccupied with identity in the Western world, beyond the cases of a few, very interesting, African artists? One case that seems particularly interesting to me is that of a work by Marcel Broodthaers; in reality it is the comparison of two works: “Fémur d’homme belge” and “Fémur de la femme francaise”, made between 1964 and 1965. It’s a case of some bony remains, femurs on which the artist made a small intervention: painting them with the colours and distribution of the Belgian and French flags respectively. A bone belongs to an individual, it is invisible until it loses all its musculature and the flesh surrounding it, but Broodthaers suggests to us the irrational possibility of adjudicating a nationality to these bones, solely by painting them with some colours in a specific arrangement. (In 2010, the Mexican artists Jonathan Hernández and Pablo Sigg carried out a rereading of the work of Broodthaers in a piece entitled “Fémur de elefante mexicano”. Here, the game is carried to the ultimate consequences. In Mexico there are no elephants, and therefore, the artists question the very concept of national identity by negating the possibility that a pachyderm be Mexican, even though the colours of a flag, those ever so direct visual signs, can make us see the opposite.)

I’ve just written that it’s legitimate for an artist not to feel drawn to these subjects. Even, if it is to refute them as in the aforementioned cases. That’s how I see it. But I also can’t hide that in some cases, I very much fear, this lack of preoccupation arises from a bad interpretation of globalization. The supposition would be that some artists (Catalans, Spaniards or of whatever provenance) might think that working with the indigenous territory, about one’s roots—though they might be of mixed race—, about an endogenous tradition, about the political symbolism of a small country, etc., was a deficiency. As if it was necessary for all the artists of the world to follow similar trajectories in line with what the decisive international centres exhibit in their halls, in order to be modern. Or postmodern. And to me it seems that globalisation has brought in its wake many delusions: we can be connected instantaneously with the world, but in the new globalizing regime the art centres with power haven’t varied that much. And the artist has to decide if in order to work, he departs from his closest reality or chooses another with which to move forward. The models have been invented: Casas and Rusiñol went to Paris and, when they returned to Catalonia, painted scenes of Paris in a Parisian style; a few years later, Joan Miró travelled each year to Paris, but there painted the landscapes of Camp de Tarragona and figures with the “barretina”.

Silence has also come from the world of museography. Few voices have reflected on what the creation of a new State could mean with regard to the collections that they might inherit and, above all, those that they would need to expand. Or reconstruct. Could an independent Catalonia survive with the current network of museums and art installations with which it counts? Everything indicates that the current structures could reveal huge potential. However, there is an urgent need for really open policies in contemporary art on the part of the public powers. If the art of now isn’t cultivated, Catalan museums of the future will be empty of content or expendable. The conservation and diffusion of the art of the past is one of the priorities, but it can’t be the only one. The previous CoNCA carried out a report into the need to create a collection of art works, organised with public funds from the Generalitat, along the lines of the model that the French State implemented after the Revolution, but the remodelling of the Consell de les Arts (Arts Council) propitiated by the CiU government, left the initiative in nothing. Will we have to wait another two hundred years?

On the other hand, in the case of an independent Catalonia, the timorous positions that have been maintained since the transition with regard to the allocation of the artistic patrimony would need to be abandoned. A recall of everything that, in purity, ought to pertain to Catalan collections and that has invariably gone elsewhere wouldn’t be out of place. I’m referring to all those donations to the State on the behalf of the family of the artist, to works like La chutte de Barcelone, by Le Corbusier, also confiscated in the Reina Sofía; to several pieces by Picasso; to a reconsideration of the distribution of the Dalí legacy; and to a whole list of allocations (pillaging?) that have corroborated the words of pluralism and decentralisation with which democratic Spain has filled its mouth, but which were all lies.

I can’t end without referring to criticism, or critical thinking, to those that have —that we have— the task of generating debate, arguments and contrasting opinions. I’ll be brief: upon us rests the worst of condemnations. In the face of the outcries of politicians, economists and journalists, we’ve held our tongues. They, that usually speak as if they represent us, have imposed some restrictions on the debate of very little magnitude, limiting themselves to the very margins of political representation within institutions, forgetting that everything began with a movement far removed from partisanship. And within these margins, art and culture have disappeared, ignoring the importance of contemplating these registers. But it’s our fault. Silence has never been propitious when history calls for the taking of stances within art and culture. Or, if nothing else, discourses.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)