Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Philip Johnson’s 1949 Glass House, in New Canaan, Conn. View of the entrance.

Philip Johnson’s 1949 Glass House, in New Canaan, Conn. View of the entrance.At the end of the 1920s, Sergei Eisenstein’s wild imagination was focused on various projects of an utopian nature. In November 1929, he met with James Joyce in his Paris apartment, to consider the possibility of adapting the world’s most unadaptable novel to film. «A ghostly experience» is how he defined the meeting in the claustrophobic and dimly-lit room with Joyce, who at that time was practically blind due to an illness derived from syphilis. Eisenstein also had just partially lost his vision during the tremendously rushed editing process of October, under the relentless pressure of Stalinist censorship. Although the adaptation of Ulysses would not go beyond the embryonic stage, his meeting with Joyce would mark the work of Eisenstein, illuminated by Joyce’s attempt to synthesize nothing less than the entire history of humanity in a day in the life of a common Irishman. In Eisenstein’s notebooks, the Ulysses project is mixed with other, no less grandiose ones, including An American Tragedy, based on Theodore Dreiser’s successful novel, and in particular the adaptation of Marx’s Capital, which he imagined as a staging of the essential concepts of the Marxist dialectic and the history of the class struggle through the flow of thoughts, memories, intuitions and desires of a worker during a work day.

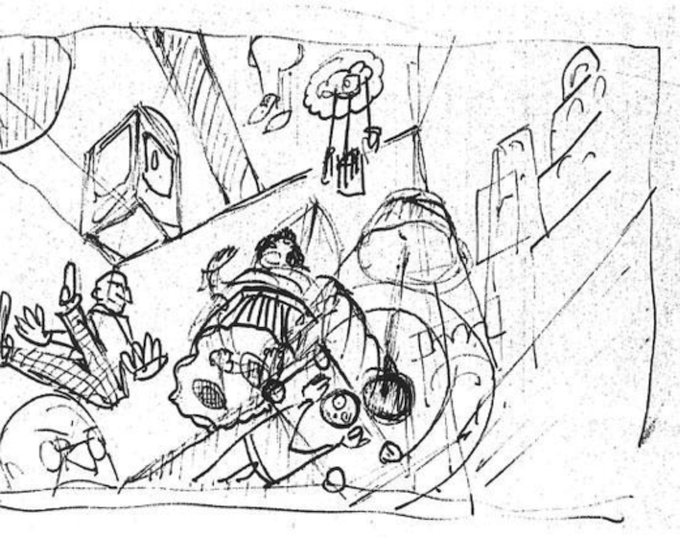

Eisenstein’s sketch for The Glass House.

The enigmatic comedy Glass House, the first of his failed proposals for Paramount during his unsuccessful American residency and his most beloved project, is also from the same period. The action of the film took place in a residential glass skyscraper, inhabited by blind and voyeuristic characters, including an idealistic architect, a robot who was the perfect citizen and a visionary poet who questioned the validity of this architectural model. If his Capital project functioned as a temporal synthesis (the history of the class struggle concentrated in a single day of a worker), The Glass House displayed the same obsession with synthesis in the spatial dimension (the contemporary model of society represented in a building). The Glass House parodied the glass houses so dear to architects of the time, which for Eisenstein brought together all the utopian and dystopian impulses of the American way of life, the voyeurism and exhibitionism of the effervescent mass culture. The odd inhabitants of this skyscraper found themselves both exposed and driven by the insatiable desire to see. In the fantastic preliminary sketches for the film, we see them witnessing a neighbor’s suicide and love-making through the glass walls of their apartments.

The glass also served as an excuse for formal experimentation. Eisenstein wanted to fully utilize the theory of the unchained camera of Karl Freund, with whom he had talked at length during a visit to the set of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis about his revolutionary conception of mise-en-scène. The classic model of cinematographic representation was shattered inside the glass skyscraper, where there were no precise points of reference or clear limits. The characters and objects floated in a transparent and shapeless structure, reminiscent of El Lissitzky’s Prouns, with the camera revolving around them in unforeseen high-angle, low-angle and vertical tracking shots that turned glass into the birth of a new way of seeing, not very different from how Le Cobursier was using the same material to invent a new way of living. This was at the time of the Ville Radieuse project, where glass skyscrapers played an essential role, and it was Le Corbusier himself who once said: “I have the feeling that, when I design my buildings, I think the same as Eisenstein when he makes his movies.”

The Glass House never came to fruition despite the involvement of Paramount, the enthusiasm of Le Corbusier, and the patronage of Charles Chaplin (who would later pay homage to Eisenstein in a scene from The Great Dictator in which Hynkel speculates about the construction of a glass palace), but the history of cinema, a proud school of peeping toms, would generously take up Eisenstein’s baton, albeit freeing it from its quixotic airs, to continue reflecting on the unusual link between glass architecture and the pleasure of looking. I won’t enumerate the long list of films about scopophilia that, in popular imagination, champions without debate Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window. The task is beyond the intentions of this article. I think, however, it’s worth remembering its naughty twin Body Double, in which Brian de Palma turned John Lautner’s famous Chemosphere House into the paradigm of the voyeuristic watchtower, a UFO-dwelling detached from the ground, elevated on a Los Angeles hill, emancipated from the steep cliff on which it rests, surrounded by glass, a kind of panopticon dream from which Jake, an actor in crisis, spied on his ravishing neighbor Gloria with a telescope. Here, unlike in The Glass House, transparency marked a clear directional component (the eternal delirium of the male gaze), but de Palma also tried to uncover the insidious reverse side of voyeuristic pleasure, and his protagonist ended up paying the price for his appetite for observation, entangled in a shady criminal plot.

Lautner’s Chemosphere House. (c) Joshua White.

Eisenstein’s glass skyscraper and the Chemosphere House are part of a long tradition within architecture which made transparency one of the founding myths of its modernity, appropriating the glassy dreams that Goethe had so finely put into words with his contribution to the great literary genre of famous last words spoken on one’s deathbed: “Light! More light!” Perhaps he was only asking for the curtains in his Weimar room to be drawn for a better view, but I prefer to believe that he was invoking an ambitious utopia projected into the centuries to come. Only a few years later, Joseph Paxton, with his Crystal Palace in London (1851), would establish an extensive genealogy of transparent buildings whose impact on the collective imagination can be traced to the present day. This genealogy oscillates between the utopian and the purely playful, from the famous Crystal Pavilion by Bruno Taut, created to provide the space for a new, improved humanity, to the characteristic glass cube of the Apple Store on Fifth Avenue, the ultimate symbol of neoliberal consumerism. It would create a series of small revolutionary impulses along the way: the dematerialization of construction elements, spatial penetration, the liberation of air and light, the disappearance of ornamental elements for the sake of functionality, and a growing desire to blend in with the environment, with the light structure of steel and the glass wall as agents of change.

Cristal Palace in London. (c) Philip Henry Delamotte (1821-1889). Smithsonian Libraries.

“We live for the most part in closed rooms,” wrote Paul Scheebart in his important 1914 essay Architecture of Glass. “These form the environment from which our culture grows. Our culture is to a certain extent the product of our architecture. If we want our culture to rise to a higher level, we are obliged, for better or worse, to change our architecture. And this only becomes possible if we take away the closed character from the rooms in which we live. We can only do that by introducing glass architecture, which lets in the light of the sun, the moon, and the stars, not merely through a few windows, but through every possible wall, which will be made entirely of glass, of coloured glass. The new environment, which we thus create, must bring us a new culture.”

The most exalted fantasies crystallized around this vision. Even Walter Benjamin spoke on the subject: “Living in a glass house represents the revolutionary virtue par excellence. A drunkenness and a moral exhibitionism that we really need today. Discretion in private affairs has gone from being an aristocratic virtue to increasingly being a matter of petty-bourgeois social climbers.” And also Benjamin: “Glass, in general, is the enemy of mystery and private property,” referring to the desire to blow up the overloaded identity of the bourgeois home, designed and decorated to suit its owner, in order to make way for a peaceful and just universal transparency, with shades of Marxism. Benjamin imagined (how deluded!) that the path towards a more open society and politics consisted of reversing the private nature of our interiority, both human and architectural, turning the glass house into the symbol of this transformation.

“How deluded!”, I say, because one need only observe any well-known example of the architecture of transparency for Benjamin’s castles in the air to shatter. Who has not dreamed of owning, or at least renting, one of those beautiful glass cubes in the middle of a forest, which seem to contain the quintessential way of life and the strange desires of the contemporary individual? This is not exactly because of a revolutionary impulse, however, but rather because of the same old bourgeois impulse, brought up to date with the comfort of our time.

Let us look at, to start with, Philip Johnson’s illustrious Glass House, an unavoidable reference for this essay about blind people and peeping toms, which apparently fulfills Benjamin’s dream of an (almost) total reversal of interiority. How well its stylized silhouette integrates into the surrounding landscape (“more Mies than Mies!”), as if floating on a lake of grass and nesting upon the branches of trees. How just its proportions, the light design of the metal structure, the reflection of the sky and nature turned into its true surroundings, the elegant enclosure of the interior cylinder passing through the roof and serving, in the same gesture of cleanliness, as a structural element, installation box and ventilation system. And yet, what this is in essence is not so much less is more than a proud showcase of the prosperity and luxury of a new ruling class, more machine à representer than machine à habiter?

Philip Johnson’s Glass House. (c) Blaine Brownell.

The elitist, classist, tacky, penny-pinching disdain of any social function of architecture and even an irredeemable pro-Nazi Johnson is not suspected, in fact, of participating in the candid utopian aspirations of Scheebart and Benjamin, but some insightful commentators have referred to his semi-closet homosexuality to reflect on the Glass House as a playful space and a queer act. What does the glass house hide? According to them (and here we have come to play), the modest 168-square-meter glass microcosm, designed as a retirement home for Johnson and his boyfriend, gallery owner David Whitney, and as a party room for their high-society friends, inhabited with surprising intensity over the years by businessmen, artists, writers, architects and all manner of celebrities, poses a sarcastic challenge to the puritanism of an American society that, in the 1940s, still kept any identity dissent in the closet, while hoisting the deceitful flag of freedom for the world to see. Exposing the private life of leisure and pleasure of the architect and his lover, the Glass House functioned as the negative of the panoptic watchtower of the Chemosphere House. It was a space not for looking but to be looked at in full playful effervescence, an exhibitionist manifesto, more camp than utopian, because it turned the enjoyment of sexuality and social relations into a little theater represented on a space with scandalously original theatric qualities.

Philip Johnson’s Brick House. (c) Gerard Joseph.

Like Eisenstein (another artist marked by his homosexuality), although in a very different way, Johnson chose the figure of the glass house to denounce the hypocrisy of a society that appealed to transparency as the backbone of its norms and discourses, but which, as in Poe’s The Purloined Letter, by showing the truth, concealed it. The utopia of transparency was just a mirage in the hands of a new puritanical and censorious conscience, and the glass house revealed this contradiction. This hypothesis seems less absurd when we look at the fact that Johnson did not design the Glass House as a building exempt from, but rather in conjunction with the less famous Brick House. This second home, built to welcome the couple’s guests, and incidentally to cunningly hide the most voluminous installation systems of both buildings, rises a scant twenty meters away from the first one like its evil twin, completely enclosed by walls of opaque, heavy and virtually inaccessible (the only visible openings are three large circular windows that allude to Brunelleschi’s Duomo in Florence) brickwork. This negative of the aerial Glass House hides a lubricious and exuberant interior with plaster domes, walls covered with cotton, works of art and luxurious black marble bathrooms, which completes the metaphor representing the space of concealment. Thus the utopian cycle of the glass house is closed and an ironic cycle is opened much more in line with postmodern consciousness. The Brick House is a monument to blindness that contrasts with the total openness of the Glass House. The closet and freedom. Between these two we all live.

Brick House‘s interior. (c) Dean Kaufman.

Vicente Monroy holds a degree in architecture from the ETSAM (Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid), although he works as a film programmer at Cineteca Madrid. He is the author of the novel “Los Alpes marítimos” (Lengua de Trapo, 2021), the essay “Contra la cinefilia” (Clave Intelectual, 2020) and several collections of poetry, including “Las estaciones trágicas” (Editorial Suburbia, 2018).

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)