Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In the centre of Zagreb, in a district with streets named after different leaders from the history of Croatia, there is a little street called Ulica Neznane JunaKinje (street of the Unknown Heroine). The street was given this name in 1928, in honour of an anonymous woman who died fighting against the Turks dressed as a man. After Croatia’s declaration of independence in 1991 the street was the object of various petitions on the part of its inhabitants who, erroneously attributing its name to the tragic role of Yugoslavia during the Second World War, decades later wanted to re-write the traumatic history of their city, to start from scratch. During the 90s, the artist Sanja Iveković set in motion a project to investigate the origins of this heroine, to preserve the symbolic name of this street in her native Zagreb and to this day it remains intact.

“Unknown Heroine” is also the title chosen for the first big exhibition of the artist in the United Kingdom, divided between two venues in East and South London, Calvert 22 and the South London Gallery that can be visited until 24 February. The title is spot on, as studying the work of the artist, that considers the construction of the feminine identity through its political participation and how it is portrayed in the mass media, there is a subject that constantly emerges: invisible or blurred identities. On the ground floor of Calvert 22, for example, there is a small, early work on paper, where one already finds many clues for her later work. Titled “Women in Art – Women in Yugoslavian Art” (1975) it consists of a page ripped from the magazine Flash Art that shows various portraits and names of recognised artists and galleries of the time, from the United States and Europe, including Yvonne Rainer, Lynda Morris and Ileana Sonnabend. Beside it Iveković drew the portraits of their Yugoslavian equivalents, but in this case without captions. There, women in art “lacked” a name and as such any recognisable agency or identity.

In “Triangle”, one of her more celebrated performance actions, this (in)visibility acquires another nuance. In 1979, during an official visit of President Tito to Zagreb, with the city full of police, the artist carried out an action on the terrace of her home, which was situated right in front of the hotel where the meetings would take place. Having seen a policeman with binoculars and a walkie-talkie watching the area from the roof of the hotel, Iveković sat on her terrace, drinking whisky, reading “Elites and Societies” by Tom Bottomore, simulating that she was masturbating. After only a few minutes, another policeman who was guarding the street called at the artist’s door and gave her the order to “clear the balcony of people and objects”. The three actors in this situation are the vertices of a triangle converted into a panopticon, that talks of surveillance and repression, above all of that of a female body that expresses sexual desires and a desire for emancipation.

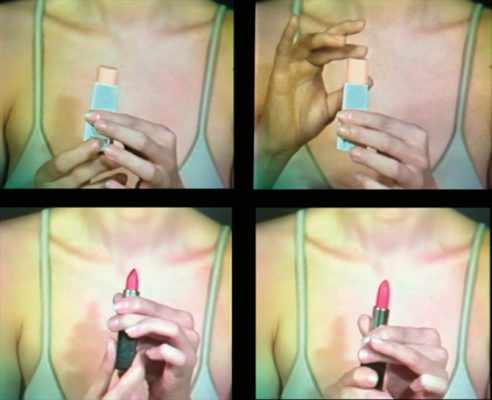

In the videos “Make Up make down” (1978) and “Practice Makes a Master” (1982-2009) the face of the female protagonist is never shown. The highly sexualised gestures of a woman making herself up, of which we only see a fixed shot of her arms and torso, or the repeated tumbles of a woman, whose head is covered with a sack (with a disturbing result that is half way between torture and comedy), can never be associated with a face. Here once again, Iveković denounces the seized or interchangeable identity. The feminine condition dispossessed of its specificity, of what makes a woman unique.

The media, from women’s and fashion magazines to soap operas and advertising, are for Iveković one of the main perpetrators of this manipulation of the female genre. In her famous series of photomontages “Tragedy of a Venus”, “Double Life” or “Sweet Life” (all pieces from 1975-1976), the artist mixed photographs taken from her personal photograph albums and contrasted them with photographs of famous women, models or even Marilyn Monroe herself. The poses and actions portrayed are always similar, but the contexts are invariably different, thereby indicating the similarities of women’s aspirations, regardless of their social or economic context, and how the unifying and colonising effect of the media can so perversely condition our everyday acts. In the series “Bitter Life”, made at the same time and employing a similar methodology, the artist contrasts photographs of models with images of young women who had disappeared. The questions that are asked here are truly horrific: is the media’s capacity to aestheticize and homogenise so great that is able to convert any female image into an object of desire, even that of a woman who has disappeared or been murdered? Is the very suggestion of violence towards the female sex something that is sexually gratifying? A latent perversion in more minds than it might seem at first glance.

One of the more interesting aspects of the feminist work of Sanja Iveković (or of her “interventions”, as Griselda Pollock would specify) is that her critical agency is never compromised by her stance in relation to certain conventions associated with the idea of “femininity”. In this sense her position regarding the use of her own body in her pieces recalls that of other performance artists active in the 70s, such as the North-American Hannah Wilke or Carolee Schneemann. The work of Iveković never denies the craving to be desired, inherent in the feminine condition. This tension that runs through her exploration of the slippery terrain between the rejection of the role of passive sexual object of woman in favour of one of highly committed political activity, while alongside exploring some of its conventions (the search for beauty, the creation of a family) is what makes the encounter with her work such a stimulating experience, and at the same time one that is so hard to digest, for a woman as much as for a man.

The artist said in a recent interview, “One of the advantages of living and working in the heart of socialism is that you learn very early on that there is nothing that is absolutely free of ideology, that everything that we do has a political charge and the division between politics and aesthetics is entirely erroneous. I think that my work reflects this”. Nobody could have put it better.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso is interested in the points of friction between criticism and curating, and how productive this tension can be. She wants to communicate the discourses of contemporary art to the widest possible audience through: essays, reviews, interviews, exhibitions and webs. She collaborates with a variety of media, such as frieze and Art-Agenda, as well as artists and institutions. Her two web projects are [SelfSelector->http://selfselector.co.uk/] and [Machinic Assemblages of Desire->http://machinicassemblagesofdesire.tumblr.com/].

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)