Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

I read an entry, in The Digital Reader, where Nate Hoffelder talks about the possibility of Amazon considering setting up a platform for second-hand e-books . The news caused a certain amount of furore in the specialised media and even hit general newspapers, like El País. Though, initially the idea might seem somewhat extravagant, there are few reasons why one could think the project might be in earnest.

In his blog, Hoffelder explains that Amazon has patented some software that not only makes it possible to sell used e-books, as well as audio and video archives and computer programmes, but also makes it possible to limit the number of times these can be transferred from one device to another. In practice, this would enable Amazon to agree with the editors the number of times a certain “copy” of a digital book could be sold. The ultimate aim would be to create a second-hand market, where the possessors of electronic publications could resell them, on the understanding that it would be at a lower price than “new” publications.

The project is a meaty one, given that it means handling digital archives, virtually reproducible an unlimited number of times, as if they were physical objects, that is to say like material goods, the duplication of which is often expensive and laborious. Through the utilization of the well-known DRM, Amazon would be creating (once again) a business model based on the logic of scarcity but applying it to a universe of abundance.

It seems shocking. But it’s not really; particularly for those of us who are linked to the world of art, and as such accustomed to seeing how scarcity can become a handy resource with which to inflate (artificially) the price of merchandise. After all, the initiative that Amazon seems to be instigating isn’t distinct from the limited editions of the art world that convert prints, photographs or even videos into limited and as such highly coveted goods. Just as with art works, “second-hand” e-books could insert themselves into the market thanks to their rarity rather than just their mere use value.

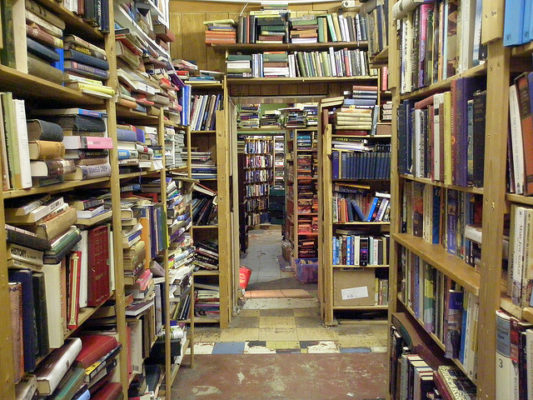

That said Amazon’s project has other implications, specifically with regard to the loss of an individual’s control over the products he/she acquires. In the universe of atoms, when someone buys a printed book, he has a total power to decide about what he wants to do with it; give it away, lend it, place it in circulation through bookcrossing or even resell it. Neither the editors, distributors nor the booksellers can ask for an account of it because, right from the beginning, they lack the capacity to trace everything that is done with the purchased work. When a reader leaves a bookshop with a book under his arm, he breaks the tie between the chain of production and commercialisation of the book. From there on in, what he does with their books becomes a mystery.

Things are quite distinct in the universe of bits, where virtual bookshops, and to a lesser extent publishers, have a greater capacity for obtaining information about what clients do with the electronic books they acquire. As is well known, Amazon is capable of obtaining a huge amount of data about the habits of the readers who acquire e-books on their web. The American company doesn’t just know what books their purchasers acquire, so much as they can also compile information as varied as; the moments when they read them, the things they leave unread or the books that they lend or share with other readers. With the e-book, reading stops being a private act, to the extent that while reading the subject slowly liberates information that is susceptible to be utilised by Amazon, for primarily commercial aims.

The creation of a market of second-hand e-books can be seen as a new twist in the control that Amazon exercises on its readers: they will no longer be just a source of information of extraordinary commercial value, but will enter into forming part of a commercial system that undoubtedly will bring them more advantages than inconveniences. In reality, the readers will be left captives of a platform where Amazon, in prior agreement with authors and editors, will be able to decide the protocols as well as the economic and legal conditions under which the resale of books takes place. If this project ends up crystallising, the Seattle company will be one step closer to appropriating the (virtual) libraries of its clients, that will lose the character of goods acquired to become services they rent.

Eduardo Pérez Soler thinks that art –like Buda– is dead, though its shadow is still projected on the cave. However, this lamentable fact doesn´t impede him from continuing to reflect, discuss and write about the most diverse forms of creation.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)