Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

During the academic year 2015 to 2016 I took part in a curatorial research programme at the Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design in Sweden. At the end of my research I received an email from the administrative department, asking me to rate the programme. The questionnaire was long and included a range of questions and considerations, most of them the same or very similar to those of other rating questionnaires I’ve received over the course of my academic and professional trajectory. With one important exception, a question that nobody had yet asked me to answer, and that began with a solemn statement: ‘Konstfack works actively to ensure gender equality at all levels’, and proceeded to ask me in what measure the person responsible for the programme had acted in this direction, both as regards the promotion of gender parity in class and the type of materials and academic initiatives implemented.

I recall the moment I read this question as an epiphanic episode, such as those in which something you’ve never noticed before is suddenly revealed to be essential and indispensable. The revelation, in this case, was that it was indeed a capital question that should be asked by all those organisations that wish to assess the competence, effectiveness and quality of their educational programmes. Almost immediately, the revelation gave way to a feeling of surprise and indignation, both with the world in general and with myself in particular. Why hadn’t any of the academic or professional institutions I had attended or formed a part of over the course of my career asked me any of these questions? And why hadn’t I considered the issues relevant enough to have been posed as questions to me? Furthermore, wasn’t it paradoxical that I should be asked precisely that question for the first time in the bosom of a society characterised by parity? In one of the countries that year after year occupy the first positions in the ranking of states with a smaller gender gap and which, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), leads the promotion of equality in the public sector?

I immediately realised that it wasn’t at all paradoxical, and that in their very formulation all these questions contained the answers I was looking for. It is in societies that have achieved greater gender parity that the question of gender inequality doesn’t seem to be a popular concern and yet is a state concern, a cross-cutting issue in all governmental policies, structural and continuous. Consequently, all Swedish universities work actively to implement gender equality; the issue isn’t perceived as a problem in classrooms but it is present in all assessment questionnaires. This government action is also responsible for most schools having advisors on issues of parity, and for the fight against all types of discrimination being one of the cores of the Swedish national curriculum. Initiatives such as Egalia, a school in Stockholm for children aged one to six that promotes gender-neutral education in several ways, beginning with language itself, consciously using a gender-neutral pronoun to avoid ‘she’ and ‘he’, and continuing with the careful choice of books and other reference material to avoid stereotyped representations of gender and upbringing, are the result of the same political conviction.

Another Swedish initiative led me to meet Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I had read somewhere that copies of her book-length essay ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ (which I subsequently learnt was the adaptation of a TED talk she had given) had been handed out to all sixteen-year-old students at Swedish secondary schools. I discovered later that the initiative was promoted by the Swedish Women’s Lobby (an organisation based on feminist principles that fights for the implementation of full gender equality, both in Sweden and in other countries), whose president Clara Berglund declared that she hoped the book would spur a debate on gender equality and feminism among young Swedes. This measure, which I believe would prove quite controversial if it were applied in Spain, was established in collaboration with different organisations, including the Swedish National Section of United Nations and Albert Bonniers Förlag publishers, and in general terms was approved by Swedish society at large. Nevertheless it received some negative criticism, such as the ideas expressed by journalist Madelaine Levy, who remarked in her column that Swedish students, who have been educated under feminist parameters, could feel that the contents of Ngozi Adichie’s book were somewhat out of date. Well, if that’s the greatest criticism of an initiative that leads to all Swedish teenagers receiving the gift of a feminist book written by a black Nigerian woman we could perhaps declare that the equality policies that Sweden has been actively implementing since the decade of the seventies have had a positive influence.

But to return to Ngozi Adichie, it is probably worthwhile thinking about whether the contents of this book of hers, and of her other essay ‘Dear Ijeawele, Or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions’, are really out of date or could appear to be out of date. Perhaps we should begin by saying that Ngozi Adichie is, above all, a writer of fiction and that her bibliography contains three prize novels, the last one of which, Americanah, won the prestigious National Book Critics Circle Award. She declares that, even though she has considered the possibility of writing an essay on specific social problems (such as racial confrontations in American society, for instance), she prefers to save her energy for fiction because what truly makes her happy is telling stories. So, Ngozi Adichie doesn’t come from the academic ranks of feminism and gender studies. Indeed, she has occasionally revealed her mistrust of the sectarianism of these university environments, which she believes usurp, with their brainy jargon, a cause that should be universal. Her two brief feminist essays are in fact far from the theoretical complexity of authors of reference such as Judith Butler or J. Jack Halberstam. They intend to be accessible to the general public, and even to raise the awareness of those who aren’t at all conscious of the feminist cause.

Some of the women who have read these two little books by Ngozi Adichie have told me that they find it difficult to identify with her discourse because she takes as her starting point the Nigerian context, the structural inequality of which they feel has been overcome in our society. I agree with the idea that some of the situations she describes could seem to be remote, as when she tells us that in Igbo culture important decisions that affect families are made only by men, or that unaccompanied women aren’t allowed in certain bar and nightclubs in Lagos. While it’s true that there is no explicit cultural tradition in the West that excludes women from the making of family decisions, quite often the weight of conservatism, patriarchal mentality and the lack of economic independence of many women means that their voices aren’t heard. I don’t know of any bar or nightclub in my city that forbids the entrance of unaccompanied women, but I do know that there are many women who wouldn’t go out alone at night even if they felt like it, and many others who, if they do, have a much greater risk of being intimidated than if they are men. Ngozi Adichie also speaks of the need to reject the idea that maternity and working life are mutually excluding. This could appear to be something too obvious, but statistics on the percentage of women who reduce their working day, or give up their jobs after having had children seems to indicate that it isn’t that clear, particularly in comparison with the extremely small percentage of men who do so in their place. She also tells us that in Nigeria money is associated with masculinity and that it is always expected (even by women) that the man will pay. Although we may think we are removed from these opinions, I myself have very often seen how restaurant bills are automatically handed to my male companion. Ngozi Adichie also describes how in Nigerian society young female virgins are praised and yet young male virgins aren’t, and how the expression of desire is interpreted very differently if it comes from a man or a woman. Our society doesn’t judge sexual attitudes and behaviour neutrally either, but according to whether they come from men or women, and in the West, as in Nigeria, the difference between gender roles also begins to be defined at a very early stage in childhood, through toys, clothes and the stereotypes propagated by popular culture. The author defends the convenience of educating according to skills and interests instead of gender, which is something we still need to argue for.

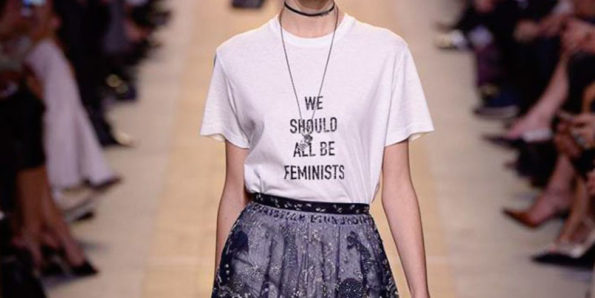

A few other men and women have also told me that Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s feminist demands are excessively obvious, very evident and scarcely complex. In my opinion they are just formulated in a very simple and straightforward way, appealing to the most elementary common sense. The fact is that the causes of gender inequality and its perpetuation may be complex, but deep down what feminism defends is essentially simple. Perhaps the problem is that because it is posed and formulated so plainly it is easily consumed and can be converted into merchandise. Some of the writings by Ngozi Adichie have ended up – with her permission – in the lyrics of a song by Beyoncé and on Dior T-shirts, and the author herself has been the face of one of the cosmetics of the giant pharmacy chain Boots. She defends herself arguing that feminism doesn’t necessarily have to be academic and anti-capitalist, and that these incursions in the popular world enable certain feminist ideas to reach the general public. But aren’t its messages and demands defused when they are absorbed by the market? Can feminism cease to be anti-capitalist and still be feminism? Can feminism be universalistic without being popular? The texts by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and their commercial echoes lead me to question whether it is possible for feminism to be a social backbone without ending up being used commercially and, consequently, depoliticised. And then I remember the Swedes, their assessment questionnaires and their intention to ‘actively’ implement gender equality.

Alexandra Laudo is an independent curator. In her projects she has explored, among others, issues related to narrative, text and the spaces of insertion between the visual arts and literature; the cultural history of the gaze; practices of resistance to the image in response to hypervisuality and oculocentrism developed from the visual arts and curatorship; and the 24/7 paradigm in relation to sleep, new technologies and the consumption of esimulants. Laudo has explored the possibility of introducing orality, peformativity and narration in the curatorial practice itself, through hybrid curatorial projects, such as performative lectures or curatorial proposals located between literary essay, criticism and curatorship.

Photo: Foto: © Ernest Gual

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)