Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

That Tuesday afternoon wouldn’t be like all others, even if it started in the most regular manner. As usual, I headed towards the underground, taking the purple line to Parallel. Taking the funicular to Montjuïc, I recalled, as I always did when walking past that side of the hill, the opening scene of the music clip of Kylie Minogue’s Slow a dive against the backdrop of Barcelona’s downtown, flat rooftops of buildings on earthly tones, lines of clothes drying in the sun. I entered the Fundació Mirò, headed towards the auditorium, and stepped in. There were already some people inside and once more—every week the same sensation—I felt socially awkward for my lack of capacity to interact with my colleagues. They seemed so well matched as a group, and I was the constant satellite, gravitating on their periphery, a magnetic force keeping us miles apart.

Then she came in. No taller than my 12 year-old sister, thick brown hair, huge almond-shaped eyes -‘olhos de Espanhola ‘, Chus Martinez about to start her seminar at my MA programme that day. Ignorant as I happily was in that period, more preoccupied with my subsequent sexual adventure than with Krauss or Adorno, I had no idea of who this petite woman with big eyes was. Yet she fascinated me on the spot. I was very good at falling-in-love in those years.

She came to speak about boredom, and I never understood if she was trying to be in tune with her topic because she spoke at a steady pace, made no hand gestures and didn’t adopt humour as a strategy of engagement. Behind her, a huge video projection of Asian girls running around an anonymous high-school gym resonated with her theory. It was indeed a boring video, but either despite or in spite of that, it was very hypnotic. I wondered if the artist would be comfortable with becoming an illustration of boring art.

All my life I’ve suffered from a terrible form of ennui, which prevented me from taking an active part in my own life and gave me the irritating allure of a cynical person. Now, this woman in front of me was giving me a tool for life, teaching me to make the best out of my boredom. I loved her very much for that. I wanted to follow her to Bilbao. I wanted to be as smart and fast and original and tiny and vivid as she was, instead of the languid bored blonde I was. But that would prevent me from putting her message in action, so I just continued drinking from her words.

This led me to practice the transformation of the matter of boredom into words as a quasi chemistry procedure, and to pursue writing as a mode of engaging with the world. That’s why this article, published more than ten years ago in the very first issue of A*Desk felt like such a joyful, relevant and timely encounter.

Text selected: Moderate your enthusiasm, by Chus Martínez. Published 6 February 2006

MODERATE YOUR ENTHUSIASM[[(translated into English, August 2016)]]

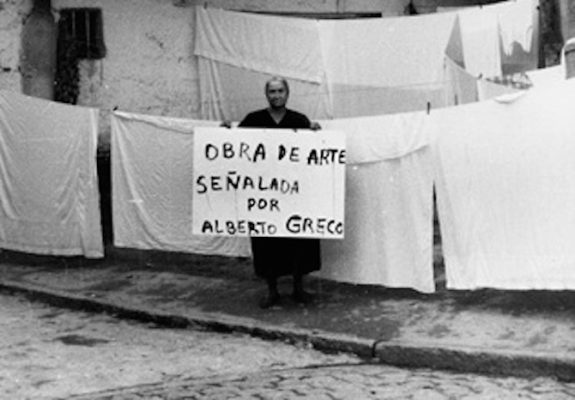

“Steal ideas from me? If everyone dares, I´ll sign” (Alberto Greco)

In a text half way between a reproach and a chronicle, Luís Felipe Noé narrates in a few pages the feats of the mythical Alberto Greco, one of the most influential artists in Buenos Aires during the sixties.

The text is written on the occasion of a commemorative exhibition held in the Carmen Waugh gallery in 1970, five years after his death. Greco took his own life in Barcelona in 1965, although not before writing the word FIN (END) on his left hand and annotating the details of his agony on the label of a bottle of red wine. Greco had apparently announced on various occasions his desire to make his own death his masterpiece. Of these, perhaps the most pertinent quotation in this context is a survey carried out in 1960 amongst the most prominent members of the art scene in Buenos Aires in which they were asked about their projects for the following year. Greco’s answer was emphatic: “commit suicide”. It’s not known the motives that led him to postpone such an ambitious project, but his declaration leaves no doubts about the importance he conferred upon it, not only within the unavoidable dialectic between life and death but also within the ambit of his artistic practice.

Greco, like many others of his contemporaries, was perfectly aware, of the post-media condition of contemporary art. If Modernity was set on defining and proclaiming the specificity of the medium, par excellence, of painting this itself had pushed open the doors to the negation of the essential and an embracing of the general, that which pertained not just to art so much as to the sphere of life. The metaphor of an indivisible unity, typical and constituent of a unique experience and unobtainable by any other means had been left historically exposed, as never before. Alberto Greco know it, such that he can propose his suicide as a legitimate artistic action, that shouldn’t be understood as just a personal act of desperation. However, Greco’s act demonstrates the power of that aforementioned metaphor, of the echo, the strength of the historical tradition on the premeditated and instigating act of this artist. Any gesture or theory that points towards the existence of a protected “interior”, removed from an “exterior” is a metaphysical fiction. This we’ve learnt at the hands of Derrida, who knew how to formulate it in the context of an era that suspected it and behaved correspondingly. Be it “interior” of a work of art as that opposed to its context or understood as a peak moment of the lived experience, as opposed to its repetition in memory or signs, is in both senses a fallacy. The idea of the specific, or the genuinely specific, can’t arise

Writing ought to be able to constitute itself as a sphere in which to explore the families of references that have served to explain, illustrate and corroborate what was happening.

Greco’s suicide takes this suspicion to an extreme. Nothing seems more our own than one’s death. The principle of identity seems to be left proven at this very moment that limits experience, a moment that can’t be transferred or communicated. The death of Greco is designed to be thought about not to be recreated as a form of experience for others. Nothing is identical to itself all interiority is constructed through exteriority, so this death, contextualised in his already mythical artistic career, is a subversive act of appropriation aimed at imploding the theory of the specificity of the artistic medium.

If we can call for anything from writing of art today it’s not the assertion of artistic qualities, so much as an investigation of the different fronts opened up after the inheritance of the 60s y 70s. The case of Arthur Danto is very illustrative in this sense. The North American philosopher and critic enters into digressions about the role that theory and writing ought to adopt “in the face” of contemporary art always within ontological parameters. It would seem that the greatest preoccupation of philosophy, and a large part of criticism, is still determining the nature of the entity, whether it is or isn’t art. On one hand, art is a phenomenon that has never stopped existing and on the other philosophical theory doesn’t know how to tackle the doubt of the end of art announced by Hegel. Danto finds an answer, the first part of which reconciles the unavoidable reality of the practice with the ineffectiveness of a discipline to account for it. Art, Danto discovers, hasn’t ended. What has come to an end is the historical form of art. What we have exhausted is the “ontological” model that explained art in the face of reality. Hence why it can be announced, always according to him, that we find ourselves confronted with a post-historical art. Up to here, it all seems like good news. The worst is yet to come.

What characterises this new stage is indifference, the impossibility of privileging anything over anything. This is not synonymous with bad art, so much as with a practice for which the motor is entropy not genius, nor the zeal to gain control of the third space between reality and fiction, as in the glorious historical period. If I mention the example of Danto, it is because it exemplifies an important moment in the crisis of the relation between art and writing. Just like Greco, Danto is conscious that we can’t recur to the power of metaphysics to explain the changes and transformation in art and the social function of art. And like Greco, Danto also opts for suicide having made it clear what he had understood.

Art hasn’t ended. What has come to an end is the historical form of it. We have exhausted the “ontological” model that explained art in relation to reality.

What neither of the two seems to accept is the self-imposed limit of classification. The function of art is not to produce objects that are ontologically distinct from other objects, just as that of writing is not to establish a classification within this curious sphere. The aspirations of writing about art have much more to do with the theory of knowledge than traditional metaphysics. The notion of “quality” has been displaced by another category: relevance. What really ought to concern writing is the spectre of interaction between mental conceptions with which art operates, the endeavour to represent them, and the cognitive systems that make possible the structuring and communication between source and receptor. To define is just one minuscule part amidst all that is left for us to do. In fact, the point of departure is not the security of knowing that I’m writing about art, so much as the ambivalence that derives from writing today about a complex practice in which the consensus and antagonism it generates are of equal importance. Critical and theoretical research ought to try to elucidate how the practice of art converges or distances itself from social imaginaries, how the art object “institutionalises” certain aspects of this imaginary, and the different ideological and socio-economic cartographies that endeavour, within and outwith art, to represent what we know of as “the world”.

Writing ought to constitute a third space, not the space of legitimisation or mere verbal representation. A sphere in which to explore the families of references that traditionally have served to explain, illustrate and corroborate what is occurring. We’ve inherited a discipline and a realm, with its courtesans, if the decade of the 60s and 70s supposed a serious intent to establish a republic we need to study and compare properly the relation between past and present explanations and the system of desires we pour out each time we quote.

To propose critical works in this sense, that stem from the history of the effort of cognitive experimentation, with which any work of contemporary art worth mentioning confronts us, is, as I understand it, the best way of discovering what criticism has henceforward.

Lisbon-born Filipa Ramos is a writer and editor based in London, where she works as Editor in Chief of art-agenda. Ramos is also a lecturer in several masters programmes and co-curator of Vdrome. In the past she was Associate Editor of Manifesta Journal, Curator of the Research Section of dOCUMENTA (13). She is currently editing a book on Animals to be published this Fall by the Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)