Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

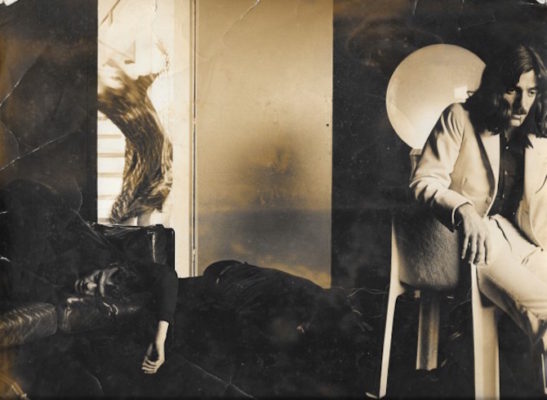

Photograph: Antoni Bernat

The new edition of Loop dedicated to a revision of the pioneers of video art, includes in its programme the exhibition Primera mort (1969), curated by Imma Prieto at the Colegio de Arquitectos. The protagonist of this show is what is considered to be the first piece of Spanish video art, which disappeared at the end of the 80s and was recuperated by the curator after a long period of silence in the archives of TV3, and restored by MACBA. It’s worth pointing out that the importance of Primera mort resides precisely in its archaeological character and in its current documentary recuperation, driven by this search for the origins that have constructed the changing history of video up until today. What is more, it is notable that they have become a sort of audio-visual palimpsest, in which a series of risky and conscious strata on the videotape are also the wound and trauma that affect the image. This passive character recognises in this initial death the possibility of encountering an already disappeared house through the camera, and what dominates is not just the very narrative of its creation, so much as the importance of its presence in the history of Spanish video art.

It is paradoxical to consider that the origin of the video is this initial, mysterious death, when what one observes is a work that could be situated at the limits of cinema verité, It is paradoxical to consider that the origin of the video is this initial, mysterious death, when what one observes is a work that could be situated at the limits of art poveraand the influence of Anglo-Saxon pop or a spirituality bordering on nihilism where not doing becomes a mandate. There is no aim in Primera mort to make poetry, art, film, painting or sculpture, so much as to shift a certain sentiment of apathy towards the discovery of the video, understood as a tool capable of configuring a negative aesthetic based on the rejection of a traditional form and wagering on the transgression of the bourgeois order from within. A certain weariness of the time, where its protagonists (Jordi Galí, Silvia Gubern, Àngel Jové and Antoni Llena) record an apparently domestic video in the house they shared in 1969 in Barcelona, showing themselves removed from a political reality suffering the international hangover from May 68 and the Prague Spring, the strike of the miners from Asturias or the imposition of Spanish martial law in a country dominated by the catholic technocracy.

How can we understand today a work of video the title of which seems to refer to the fragile character that constitutes us? What significance does the domestic space of a house acquire that has been conveniently painted black as a metaphor for isolation and a certain premonitory sepulchral spirit? The documentary realised by Imma Prieto titled Echo of Primera muerte helps us to understand what relevance the recording of a video can have in which it wasn’t just subjects inspired in the reading of William Burroughs, or those related to Wilhem Reich, like drugs or sexuality that were talked about, so much as other symbolic spaces were also touched upon offering an image of communal life fascinated by the beatnik movement and the eruption of the pop phenomenon in its Anglo-Saxon facet.

The vitrine dedicated to documentation in the exhibition of the COAC, shows how the work interweaves literary, musical and artistic themes that for the first time are included in a work of video that will be constants in later Spanish production. Pink Floyd (Several species of small furry animals gathered together in a cave and grooving with a pict), The Rolling Stones (Salt of the Earth) or The Beatles (Let it be) and the avant-garde The Fugs mixing up musical and poetical protest, can be heard in Primera muerte, introduced by Jordi Galí, to whom is attributed the fortunate title of the video. There are readings of the Naked Lunch while its protagonists appear shipwrecked in a space dominated by strangeness, posing on a sofa in the garden, doing apparently nothing, enjoying a bit of dolce far niente. A fascination that leads to a contrast between the masculine and the feminine figures, who scratch and gesticulate, talk, touch and rub against each other, where a certain lack of communication appears between the sneeze, the humming and the lassitude when the sun on the face leads to sheer indolence. This contrast between the reading of Burroughs and the appearance of the video camera as a witness contributes to show – as Silvia Gubern recognises in the documentary – a sort of phallic game in which its contribution to history can be recognised, as much from an artistic perspective as from a sexual aspect. In this sense, Antoni Llena indicated a posteriori the influence of Manet, as if the endeavour had tried to offer a somewhat ingenuous déjeuner sur l’herbe, when what becomes really evident is that the appropriation of the erotic ideas of Burroughs constitutes a significant territorial frame, converting the house itself into a first death of the ideals of sexual liberation, as Àngel Jové suggests.

In the video a series of apparently guileless symbols appear, spontaneous and improvised where the triad becomes the key figure recorded with the video camera. Antoni Llena gives an apple to Àngel Jové to eat, Silvia Gubern appears as a powerful isolated female figure, Jordi Galí seems to enjoy the sun and the company, a child holds up a chicken that is running away. They are the images of the sky through the buildings, figures that smile and dress up, but without any of the clichés of the artist in the studio. No doubt to offer this video as an exhibition of the daily experience of art and the way of working would reveal to the public of the talk that seemingly took place on the 15 May 1970 in the Colegio de Arquitectos – 47 years ago. This also supposes a significant anecdote in the exhibition- that the origins of video were entirely conceptual and their interests were very different from the plastic aspects, dominated by late Informalism or by the incipient proposals of a more experimental or social nature that would start to be introduced with the Grup de Treball, a few years later. In those, video becomes something autonomous that could be used as a political tool. This distanced character shows, on the other hand, that Catalan conceptual art took place beyond Banyoles because its interest was precisely not to be just an audio-visual work, so much as to show what it was proposed to say about the artistic action to the public that assisted a talk. Despite the autonomous character of Primera muerte, it is important to indicate its historic transcendence, although it would be worth knowing if this latitude is related to Bartleby’s negation, separating himself from a traditional bourgeois vision in conscious isolation, or if it is due to lack of attention to the political and social factors of art, that would have to become the thematic core of conceptual art. It is precisely this negative character of the inaction, one of the aesthetic interests of an early work that we can now bring up to date by discerning the death of art in the origins of the history of current video-creation.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)