Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Millions of photographs are made inside a narrow strip of land just a few kilometers wide. Exact numbers are hard to define. Perhaps it is tens of millions. Maybe hundreds. For dozens of months now, images continue to cascade without pause from the regional war in the Middle East and the ongoing Gazan Genocide to the entire planet as a recurring matter of course. Becoming something to expect, yet another set of streamed images to scroll past. When something is rendered mundane it cannot appear as urgent. Disaster has become routine. But a partisan disaster at that. Because while images of corrupted Palestinian bodies stream to broadcasters and social media with cadaverous ease, not even one single visual evidence of a harmed Israeli soldier was ever circulated to the masses. Just one side is displayed as harmed. Just one side is prone to be injured. Just one side is maimed. Just one consisting of rubbled bodies and torn limbs. Perpetual perpetrators are immune to appearances revealing their damage. Resistant to the exact actions those inflict onto others. No wonder some lives seem worth more when their death remains out of frame.

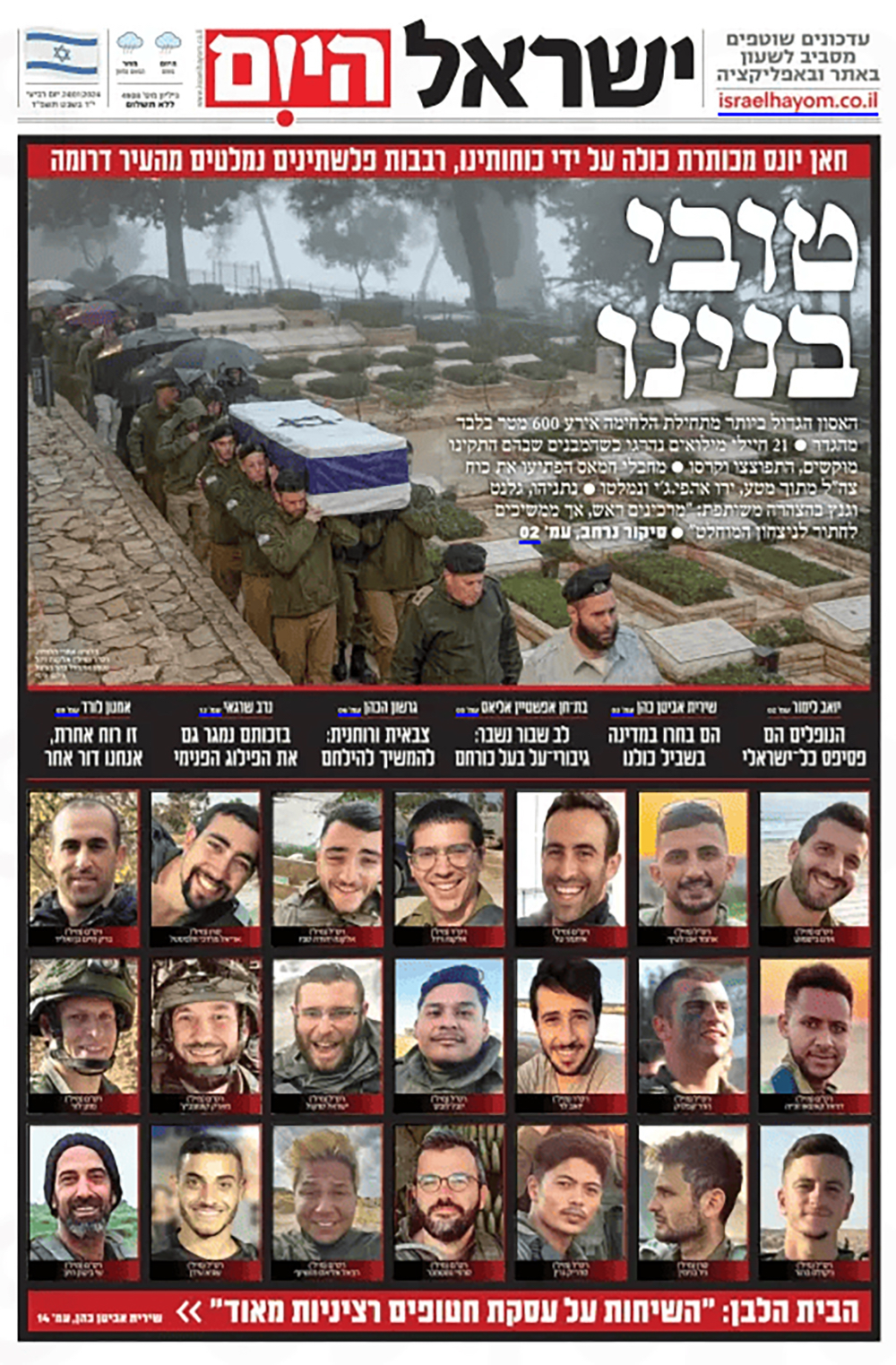

Not that this should mean soldiers never lose their lives. What becomes clear is that the photographic contrast of how wounded perpetrators are concealed and their victims highlighted entrenches their positions further and deprives the latter from a meaningful sense of agency. Two months after Israel began to transform Gaza into the largest graveyard in the world, twenty-one of its invading forces perished in an ambush. When national newspapers presented the loss on their front pages, the soldiers remained dignified. Protected from the showcased grotesqueness of their casualties, those killed in action were presented to the general public in their prime rather than demise. Exhibited even in death as living, the soldiers were depicted as some would like to remember them; encased in coffins covered in blue and white flags, accompanied with pictures of them from the time of their absolute vigour rather than evidence of their last moments. Bodies sanctified, position of dominance secured.

Cover of the newspaper Israel Today depicting the dead soldiers as living. The title reads: The best of us. January, 2024

Yet not all mutilated bodies could be represented to a large audience. When the numbers began tipping, when Israel began unleashing hell on earth and generated immense amounts of corpses that far surpassed its own, the public’s capacity to assimilate such images collapsed and the attention economy tanked. No person nor social media account could process and grasp the endless multitudes of such human loss coming in from Palestine. But given the vast number of such documented atrocities, some are bound to fall through the algorithmic cracks. While one side consists of a qualitative understanding of its victimhood, another becomes quantitative. Reduced not to the separate and distinguished individualities of its casualties, but to the sheer magnitude of their numbers. Hundreds of thousands homeless. Millions displaced. Just a few dozen exploding in a hospital last week, scores more assassinated in a privatised aid distribution center turned shooting range. Israeli hostages are recognised and spelled out like missing children on a milk carton. Posters with their faces and names on it demanding their immediate return were pasted all over metropolitans around the world, making the transition from the digital realm to the physical one, entering into public experiences of grief. But on the other hand, Palestinian hostages and detainees remain nameless. Forever faceless; just an unidentified mass. Removed from the pictorial realm, and therefore from the political one too. Photographic bias is the entire point. When someone is erased as an individual and denied their image, grieving them becomes a challenge. Mass violence and genocide dehumanises the dead as much as it does the living.

Manufacturing an audience for violence depends on imagemaking: bullies record their school abuse and share them with others. Prankers upload videos showcasing their mistreatment of lessers. No doubt, the pattern of depicting the ongoing carnage is just an exaggerated version of that. But herein lies a strange difference. During other brutalisations and warfares of past historical periods, the victors wished to present their triumphs– photographing their flags waving above occupied parliaments or hoisted above blood acquired territories. Nowadays, however, it is the other way around. Images of defeat are now those of success. Right after news broke that the Madleen Flotilla was intercepted by Israeli forces within international waters, its Minister of Defense announced that the activists onboard would be forced to watch footage of the October 7th attacks. Torture of such sort ticks like a clockwork orange. Now more than ever, the documented trauma of one group becomes a device with which to punish others.

Footage from that infamous day became invaluable political snuff. Hamas gunmen mounted cameras on their bodies to document their wholesale slaughter. Beating men to a pulp with their garden rakes. Hunting elders next to a bus stop. Kidnapping children and parading women from roving trucks. Resembling, perhaps even imitating a first person shooter video game, horrible actions were broadcasted. Yet for some reason such images of gore were not sufficient. Despite the obvious shock value of those moments, international media outlets and the political class within Israel still searched for an image so distressing, a photograph so vile, that it alone would galvanise its entire population and the rest of the world into supporting its upcoming actions within the Gaza Strip. Without it existing, one had to be manufactured. Just four mornings after the attack, The Sun shined with another hyperbolic headline when the newspaper exclaimed that savages beheaded babies in massacre. Likewise, The Daily Mail claimed that Hamas roasted babies in an oven. No proof for such supposed crimes was ever found. Both claims were contested in court and were rolled back since. But even that was too late. Forensic and journalistic evidence disproving these acts were not able to stop that manufactured image from penetrating into the minds of public consciousness.

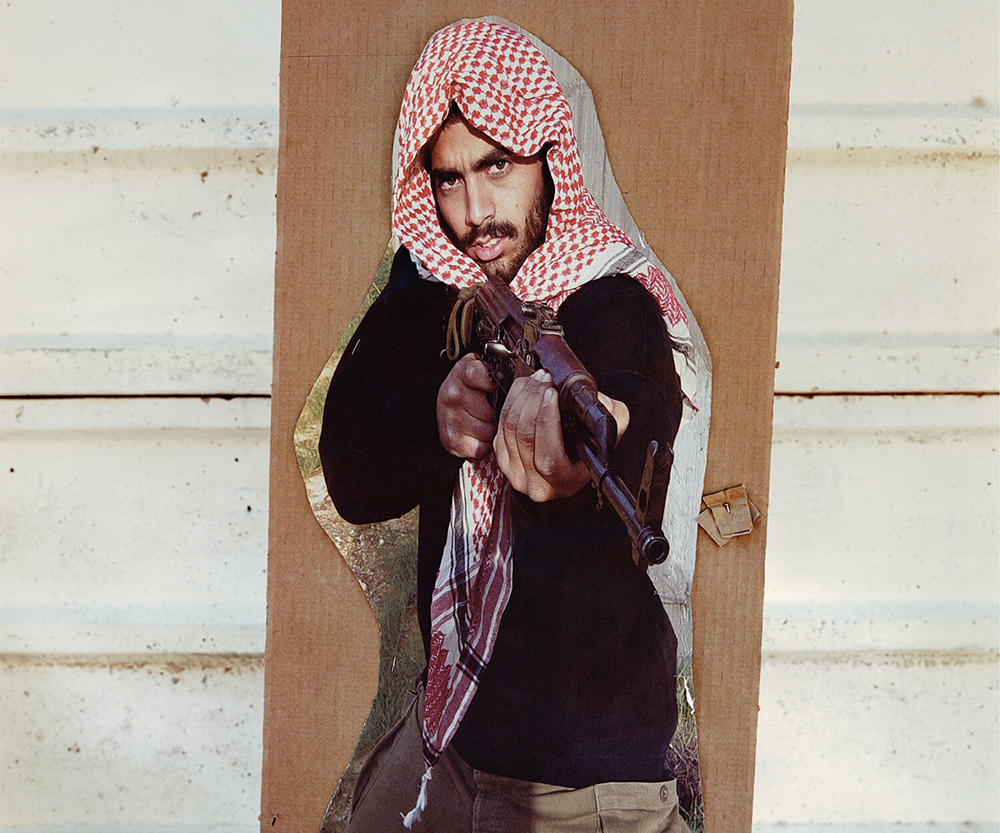

Rehashing Hansel and Gretel like fables mixed with Holocaust retraumatization, this reckless incident points to the undercurrents of clickbait warfare. It is not, as American poet T.S. Eliot once mused that Humankind cannot bear very much reality, but rather that it demands and fabricates a reality it cannot bear. Inventing the real is something that the armed forces in Israel do for a living. Deep within the dunes of the Negev desert, the Chicago military base consists of bizarre simulations that would put postmodern French philosophers to shame. Consisting of an orientalist mix of mock Arab architecture, it serves the soldiers as a training ground for potential urban warfare. The fake environment also includes target practices: Photographs of Israeli soldiers dressed in ethnic Arab garb to resemble their make-believe version of terrorists, that were printed and made into shootable objectives. Racist projection aside, the affordance of one side in a struggle to depict the other and creating them in one’s own image, provides a control over their existence.

Untitled. Copyright Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, Chicago (SteidleMACK, 2006)

From all this it is clear how fabricated images have a tense coexistence with verifiable ones. How documented violence is weaponized, contested and fabricated. Now more than ever before, the militarised landscape in Israel begins to echo the warning Sigmund Freud had made long over a century ago, that we must “be prepared to find those who have the compulsion to repeat violent acts which now replaces the impulsion to remember them.” We are then faced with two political groupings. There are those who do not wish to live in a world composed of torn limbs and human rubble, and others who regard that not only as inevitable, but even useful. For whatever reason, those who crave unimaginable obliteration of existence are called realists.

(Cover image: Israeli soldiers after watching a video about the October 7 attacks, September 11 Lucien Lung/Riva Press for Le Monde© Lucien Lung)

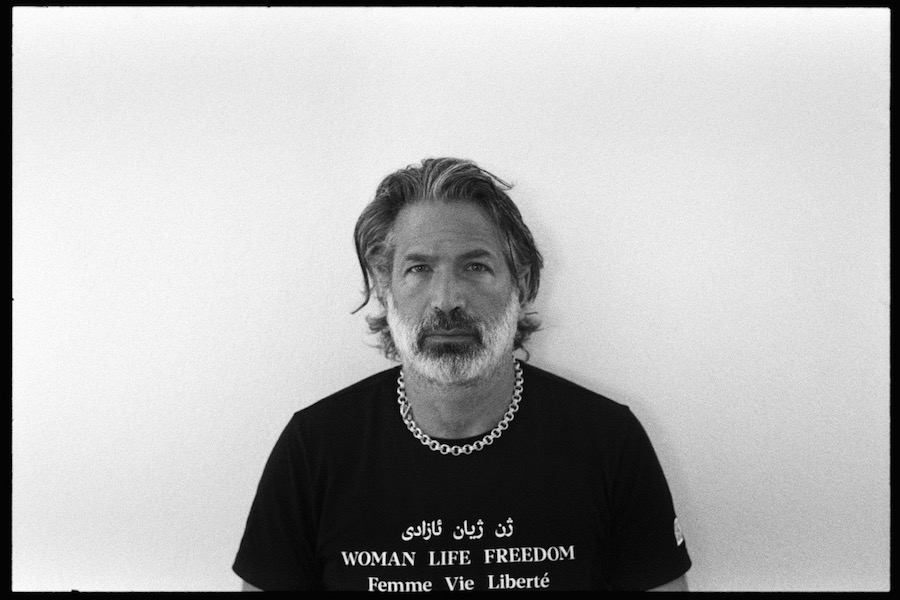

Adam Broomberg (b. 1970, Johannesburg) is an artist, activist and educator. He currently lives and works in Berlin. He is professor of Photography at Istituto Superiore per le Industrie Artistiche (ISIA) di Urbino and Practice supervisor on the MA in Photography & Society at The Royal Academy of Art (KABK), The Hague. His most recent work “Anchor in the Landscape” a large-format photographic survey of olive trees in Occupied Palestine was published by MACK books and exhibited at the 60th edition of La Biennale di Venezia.

Ido Nahari is a writer and researcher currently pursuing his doctorate in sociology. Previously an editor for the street newspaper Arts of the Working Class, his writing has appeared in numerous journals and magazines. He has lectured in various museums and academic institutions across the United States and Europe.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)