Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In my mid-20s, I experienced serious conflicts in two of my most important friendships. The conflict with friend A. was about our intensive working relationship, in which I had more say than she did, and the conflict with friend B. was about a disagreement in the arrangement of the shared rooms and an associated situation in which I was having a strong emotional outburst —but of course, it was about much more than that. “You always talk everything up,” was the response of one friend, who from then on would give me the silent treatment in the communal areas of our shared flat. “We always have to resolve conflicts with your way of talking, you leave no room for other methods and you dominate me” —was my other friend’s response. This argument also escalated into radio silence, the more she refused to talk about her feelings, the more I begged her to confide in me.

I can tell you right away that both conflicts have since been resolved. However, the resolution strategies were fundamentally different and in this article they are intended to illustrate trends in one of the most active communities on this topic.

I was part of a collective together with A. and our situation put a strain on the whole group, which is why we decided to hold a workshop as a cure. A Non-violent Communication (NVC) scene was just emerging in our city and so we invited Holger, one of the main organizers.

In the session, he told us how he had come to NVC. He had often been accused of taking up too much space in conversations —without wanting to. In his search for a solution, he came across NVC —initially through a book in the public library. Almost ashamed, he told us about Marshall M. Rosenberg, who founded NVC as it is practiced and understood today. He was ashamed because Holger didn’t like the way he was portrayed as a guru.

Nevertheless, he showed us how we can formulate observations neutrally without making value judgments about the behavior of others. He also showed us how our feelings point to deeper needs and that these needs are never anything reprehensible. He helped us to deconstruct accusations and understand what we actually wanted and how we can use this knowledge to find solutions that don’t put others under pressure. The central theme in NVC is how to ask other people for something without obliging them to this request.

An example:

My actual accusation: You don’t allow me to understand you.

What I observe: You don’t talk to me.

My feeling: Anger, frustration, helplessness.

My underlying need that is not being met: Understanding and harmony.

One way to formulate the sentence according to NVC: I can see that you are not talking to me (non-judgmental observation). I want to be understood and for us to get along well (formulating needs). I ask you is that you listen to me and try to understand me (request).

In terms of NVC, I have to be prepared for the other person to refuse the request. NVC is based on the fact that I can then satisfy this need elsewhere. This makes it atomistic —as if each person is floating around freely and could also fulfill their needs with any other person.

Repeating what you have heard is also part of NVC. This is a recommendable exercise because when our group tried it, we realized that we often didn’t listen properly. We were hardly able to reproduce exactly what was said. This is why I hardly ever say anymore that I understand something because I realized that I rarely really understand.

What I hadn’t understood until then, too, was that we had no idea of how we were supposed to talk to each other or how to listen to each other properly. After all, there is no lesson on “The ABCs of human conversation” at school.

And because there were no rules for communication, all we really had left were the toxic or implicit communication strategies from our families, school, work and university, which quickly reached their limits when conflicts arose.

NVC was the legitimate method that A. could accept (in contrast to my insistence that she should reveal herself to me). With stilted language, dissecting and painfully, A. and I followed the strange ritual in which we were supposed to become aware of ourselves and reveal ourselves to each other. We managed it: we overcame our conflict —effectively and quickly.

My other conflict with B. was resolved completely inefficiently: it took exactly four years for B. to say a word to me again —and there was no contact in between. Four years was the expiry date of our conflict. After that, it was somehow over.

I don’t know what happened to her in the intervening years and what conclusions she came to.

As much as the NVC opened a door for A. and me, it also marked the wall in the communication between B. and me. We both had no access because she didn’t want to reveal herself. In this context, I am reminded of Edouard Glissant, a philosopher and writer from the French-speaking Caribbean, who emphasized the right of the colonized to opacity. They have the right not to be understood, they don’t have to perform a soul striptease for their oppressors who want to turn their vulnerability into profit and ammunition for more weapons of oppression.

Sarri Bater, a researcher and practitioner in the field of conflict transformation in the UK, Sri Lanka, and the SWANA region, writes: “NVC is definitely and largely reduced to white, liberal experiences of feelings and needs, and this is highly disturbing and deeply tragic.” Today, she leads the organization Open Edge, which works at the intersection of conflict and identity politics as well as justice and development, focusing on relationships as the key to transforming systems of violence and beliefs. The team’s reasoning is based on NVC, although Bater noted in 2018 that in over 15 years of practicing NVC, she had never seen a focus on systemic conditions and experiences unless she brought it in herself.

Her text was a reaction to the article NVC is for the Privileged (2018) by Raffi Marhaba, a trans activist who now works at the intersection of design and social justice. Marhaba criticized the following points:

Bater shares many of Marhaba’s experiences and believes that this is due to NVC being taught as a tool rather than an awareness. She argues that NVC is so heavily dominated by white feelings and needs because most practitioners come from liberal backgrounds. Although Rosenberg himself did not claim that needs and feelings are universal, and in her experience, this is not the case, needs are often presented in this way in NVC, writes Bater.

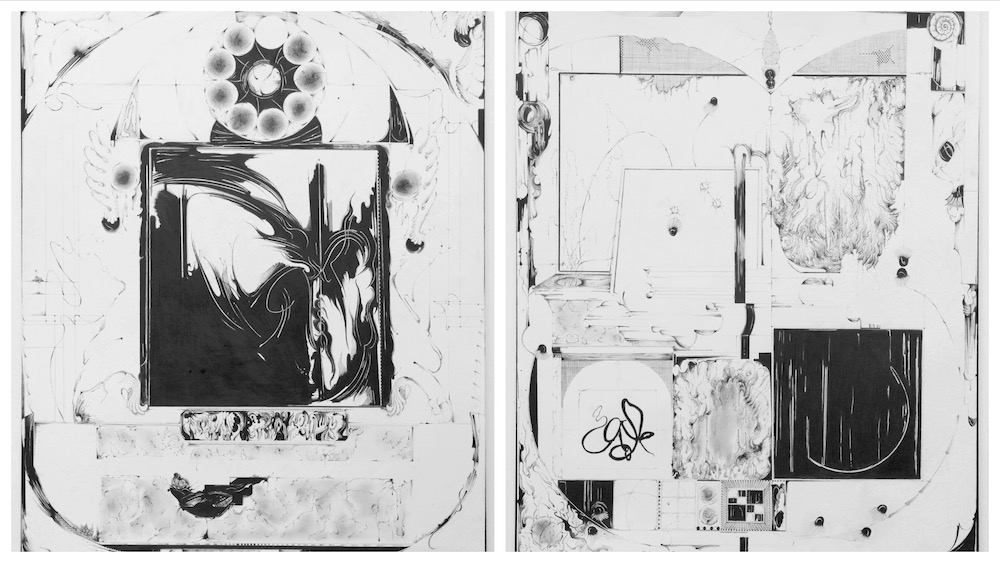

Paulina Nolte. Left: Fairy Grotto, 2024. Right: Interal System, 2024. Foto: Constanza Meléndez

According to our trainer back then, Holger, there is a definition of needs in NVC: in the inner logic of NVC, they are independent of other people. For example, a need is to give and receive love, but it is not a real need if we talk about wanting to be loved by a certain person. Therefore in NVC, it is also not correct to say that it is a need to see the other person happy.

Rosenberg’s definition of needs was based on the model of Manfred Max-Neef, a Chilean economist with German parents, who, in addressing the class differences in South America (partly due to colonialism), developed a model of universal needs that aimed to align development policy goals with a “human scale”, i.e. with the respective well-being of people and not with a gross national product. In doing so, he wanted to create an argument for a decentralized and self-organized form of democracy free of economic growth concepts. It is therefore important to realize in the debate on universalism that such demands do not always have to have Eurocentric dominance in mind.

Bater, on the other hand, criticizes the propagated universalism because structurally disadvantaged people are not included, i.e. because it is mainly produced by the white, liberal NVC community. Bater, who does not have white skin herself, is also a member of the Global North, where “gender-specific and ethnocentric (liberal) truths about the world are propagated as undeniably normal and right” and form the apparent basis of NVC.

A scientific study of the universalism debate is lacking because NVC has only been researched selectively, even though it is used today in so many contexts of business, activism, and education. One of the reasons for its widespread success: Rosenberg has been providing vivid concepts since the 1980s (“giraffe and wolf language”). He takes on a peculiar transitory role in which he transitions from science into the everyday world by offering a methodology, but loses scientific backing in the process. The only way I can explain how the sciences are avoiding NVC is that there are reservations about the spiritual part and about taxonomies that cannot be scientifically justified. Perhaps research into NVC is also unpleasant because Rosenberg has unintentionally or intentionally become a kind of messiah figure. What enabled this (old) white man to do this?

In addition to the obvious practical value of his methodology, it is also his socio-political position that has privileged him globally. His trademark, which is protected in the USA, finances a training center to ensure that NVC is passed on correctly, while at the same time, half-knowledge is increasingly spreading. A mass dimension is thus entering the field of NVC, creating gaps in thousands of blogs and reproductions that lead to the forms of violence criticized by Marhaba.

In this widespread half-knowledge, those who are not “yet” able to communicate without violence are also increasingly devalued. But: NVC requires targeted education, concentration, training, and time —resources from which a large part of the global population is excluded. Basic needs, such as water or food, often cannot be met in current systems of domination. It may be painful to become aware of unmet needs, let alone name them because there is no prospect of them being met.

Privileged people who practice NVC and can name and satisfy their needs should carefully observe how they use NVC. It is actually part of NVC to check one’s own intentions and also the consistency of body language with what is being said, so as not to oppress others through the language virtuosity of NVC. Because whoever has the words has the power —and the responsibility. NVC guidelines recognize this interdependence in the parent-child relationship —in practice among adults, exploring structural dependencies in NVC is rarely discussed.

Part of such a discussion could be dealing with non-NVC conflict resolution. My friend B’s conflict resolution worked. She did not insist on an efficient method —but because she determined the parameters of our interaction, she also had the agency, not me, who overwhelmed her with the power of speech.

A respectful addition and rewriting of NVC by other authors would lead to a gradual disempowerment and demystification of Rosenberg as the central figure of NVC, ultimately reconnecting it with communities that have been practicing aspects of NVC for decades and centuries, as well as with the communities that might emerge in the future independent of a centralization on the Global North.

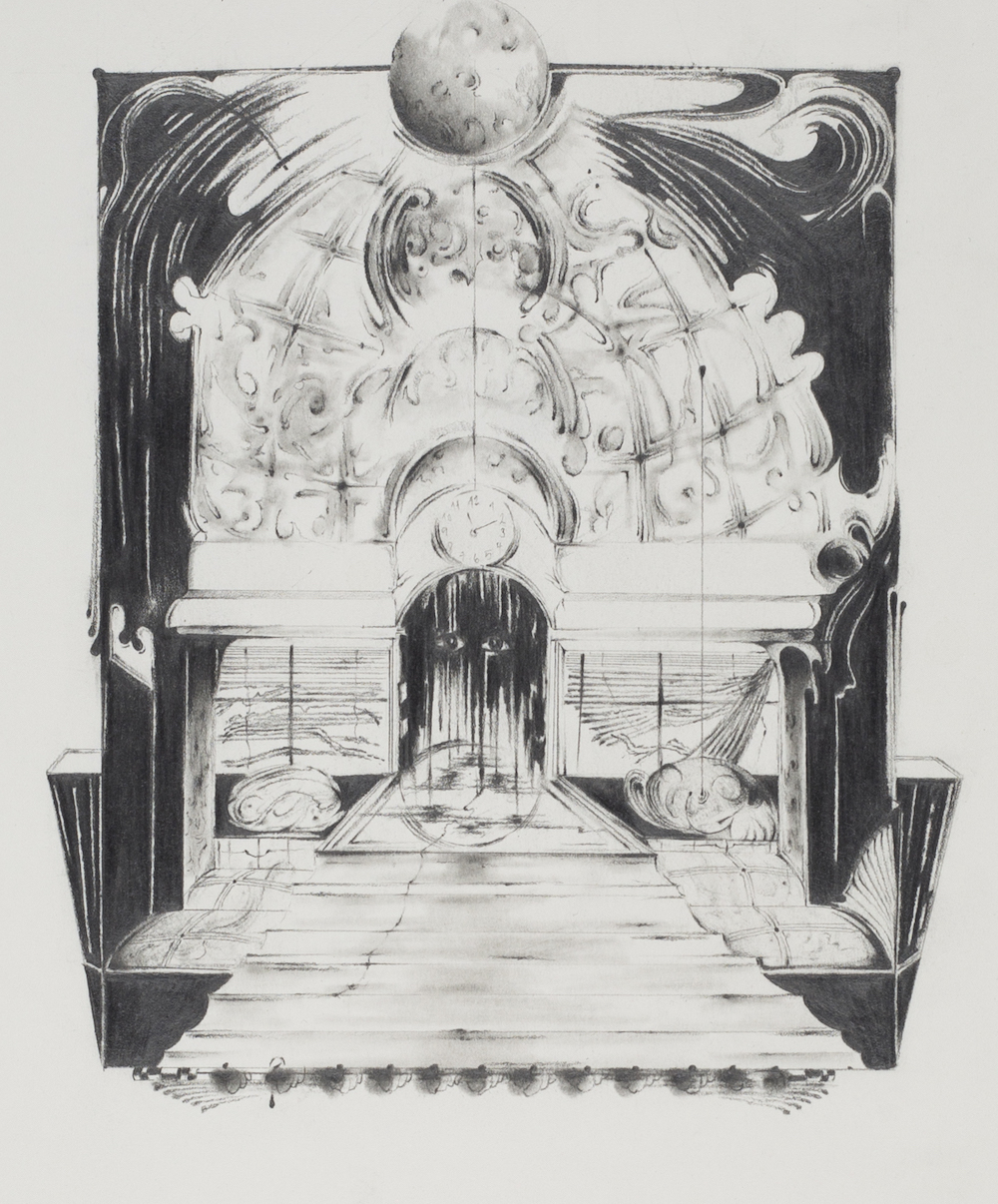

Paulina Nolte, Dream Devil, 2024. Foto: Constanza Meléndez

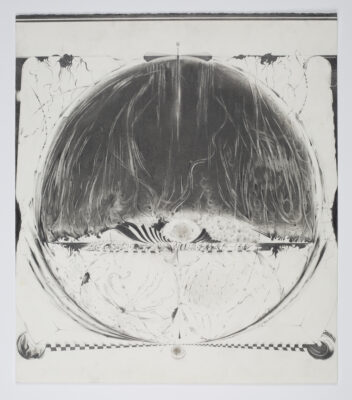

(Cover image: Paulina Nolte, Earthyn, 2024. Foto: Constanza Meléndez. All the images: courtesy of the artist)

Amelie Jakubek (b. 1990, Germany) is an artist, editor, and organizer focused on collective practice. Holding an MA in artistic research from St. Lucas School of Arts in Antwerp, she is part of the collective behind Arts of the Working Class and collaborates with Archive Books/Sites as well as the Egyptian-German Collective Commune. She has conceived and produced projects. In 2024, she co-edited But how does it change the price of tomatoes in the market? about socially engaged art.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)