Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Dominated by women’s voices and queer perspectives, the 2020 edition of the Berlin Biennial devotes to the difficulties and triumphs of marginalized communities. The eleventh iteration of the biennial, entitled The Crack Begins Within, finally opened its doors in early September and can be visited at various locations in the German capital until November 1.

What does it mean to hold a biennial in a year like this one?

Beyond the practical limitations and the fact that many participating artists cannot travel, any large art event that takes place in the year 2020 is in itself a statement about the historical moment in which we live. The curatorial vision of this final Epilogue of the Berlin Biennial —henceforth bb11— was conceived during the last two years, before the Covid-19 changed everything. It is therefore very exciting that the central themes it addresses —post-colonial struggle, injustice based on gender and race, homophobia and inequalities caused by climate change— have reached their climax in this 2020, collapsing the world through a pandemic.

Postponed from June to September, bb11 is one of the few major international art events that will physically take place in Europe this year. Distributed in four venues, the curators —all residents of South America— María Berríos, Renata Cervetto, Lisette Lagnado and Agustín Pérez Rubio, invited more than 75 women and queer artists mostly coming from the global South —some of them consecrated or already deceased, others at the beginning of their careers—, who if it weren’t for the biennial would have little chance of being exhibited in Europe. The Spanish artists present at bb11 are the collective El Palomar, Andrés Fernández, La Rara Troupé and Azucena Vieites.

From left to right and up to bottom: Agustín Pérez Rubio, pic taken in Valencia ca. 1973; María Berríos, pic taken in Edmonton, ca. 1987; Renata Cervetto, pic taken in Buenos Aires, 1989; Lisette Lagnado, pic taken in en Kinshasa, 1963

According to the curators themselves, bb11 is an antidote to the “patriarchal uproar” and “colonial capitalism,” a shout against the long-dominant white and Christian mentality and the patriarchy that enshrines it. Each of the venues articulates its exhibition discourse by rebelling against institutions such as the church, the museum, and the politic body through works of art that focus on collectivity, solidarity, and compassion.

The Crack Begins Within was preceded by three preliminary exhibitions, the first of which took place one year ago, last September at ExRotaprint, a former printing plant occupied by a cooperative of tenants in the early 2000 and now operating as a community-driven cultural center. A model that fits very well with the curatorial team message. During this final chapter, ExRotaprint works as an archive containing the biennial research and exhibition process.

“Exp. 1: The Bones of the World”, 7.9.–9.11.2019, 11th Berlin Biennale ℅ ExRotaprint. Instalation view. Foto: Mathias Völzke

In the meantime, KW Institute of Contemporary Art hosts The Antichurch with visceral perspectives on patriarchal violence and subversion: the “religion” of colonial capitalism in its various mutations. It is not an easy task to transmit forms of dissidence, resistance, and activism through artistic means without being more preachy than subversive, more didactic than revolutionary. Sometimes it succeeds and sometimes it doesn’t.

Female sensibility is the alternative to the male debauchery and that is what the Barcelona collective El Palomar (Mariokissme and R. Marcos Mota) tell with Schreber is a Woman (2020). Against the father and the patriarchy, their video installation is based on the book Memoirs of my Nervous Illness (1903) written by the German judge Daniel Paul Schreber while confined at Sonnenstein psychiatric hospital in Saxony. In these memoirs, he recounts his feeling of wanting to be a woman, among other experiences.

El Palomar, “Schreber is a Woman”, 2020. Instalation view. Courtesy El Palomar. Foto: Silke Briel

El Palomar discovers and reinterprets Schreber’s memories from a transfeminist perspective that resists the concepts of confinement and exclusion, of domestication and control, and deconstructs the Freudian link between Schreber and his schizophrenic paranoia from a queer point of view. Schreber is a Woman subverts the original circumstances of the queer lineage, recontextualizing gender and pleasure in the present.

In this antichurch, the atrium and central space of KW has become a sort of queer sanctuary, where the paintings by Brazilian artist Pedro Moraleida Bernardes —who committed suicide at the age of 22— are arranged in the form of a suspended polyptych. The six panels represent, in a brutal and neo-expressionist way, the sacred and the degraded, scenes of lust, violence, mortification, and humiliation.

Pedro Moraleida Bernardes, “Sentindo um cansaço mortal por representar o humano, sem fazer parte do humano”, 1997. From the series “Faça Você Mesmo Sua Capela Sistina”, 1997–98. Instalation view. Courtesy Instituto Pedro Moraleida Bernardes. Foto: Silke Briel

Yet there are also pieces that present the female sensibility in roles less associated with Catholic victimism, such as the monumental drawings by Argentinean Florencia Rodríguez Giles, generously installed in this very atrium. The detailed canvases of the Biodelic series (2018) represent figures from another world, muscular and graceful bodies, part human, part animal, and part plant. Her figures challenge binarism in favour of a polymorphic, extravagant, and graphically lustful bodies that empower female genitalia and engage in pleasure-driven actions.

Florencia Rodriguez Giles, “Biodélica”, 2018. Instalation view. Foto: Silke Briel

Powerful is the piece Marcha à ré (March Backwards) by the Brazilian collective Teatro da Vertigem, which documents a very contemporary dissident action, carried out on the 4th of August 2020. In it, a funeral procession of cars tries to make its way backwards along Paulista Avenue, the financial centre of São Paulo. The piece deals with the necropolitics of the extreme right-wing populist regime of Jair Bolsonaro, currently involved in the genocide of its own population.

Teatro da Vertigem, “Marcha à ré (Marcha atrás)”, 2020. Film still

Marcha à ré is inspired by the unclassifiable Brazilian artist Flávio de Carvalho (†1973) Experiência n° 2 (1931) —in which he marches backward to the Corpus Christi procession. The car parade also passes in front of a street-art piece that reproduces one of the images from Carvalho’s Série Trágica-Minha Mãe Morrendo (My Mother dying) —exhibited also here in the bb11 at the Gropius Bau. In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, the agony of Carvalho’s mother represents the right to lament the thousands of deaths caused by the authoritarian and negligent management of the current health crisis by the Brazilian government.

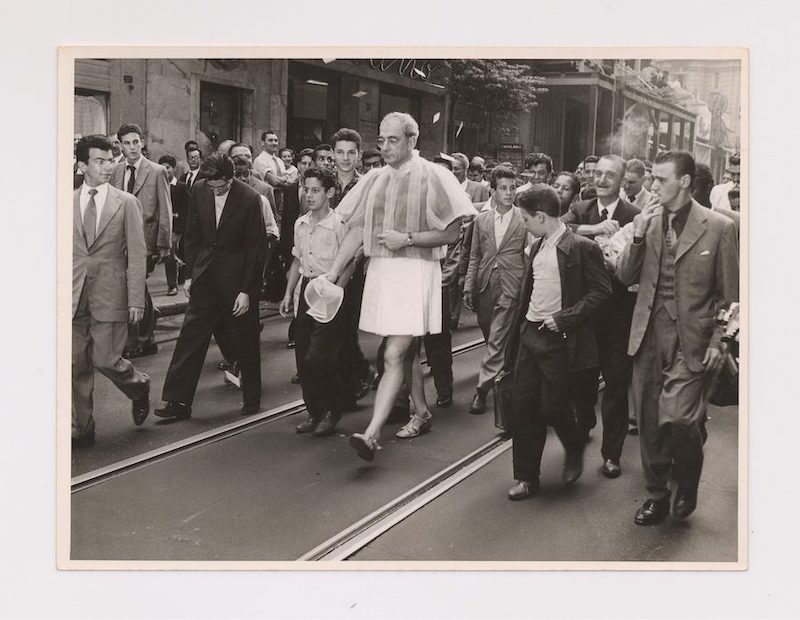

Flávio de Carvalho wearing his suit “New Look” while walking São Paulo streets, “Experiência n. 3”, 1956. Foto: Fundo Flávio de Carvalho/CEDAE-UNICAMP, Campinas © The Heirs of Flávio de Carvalho

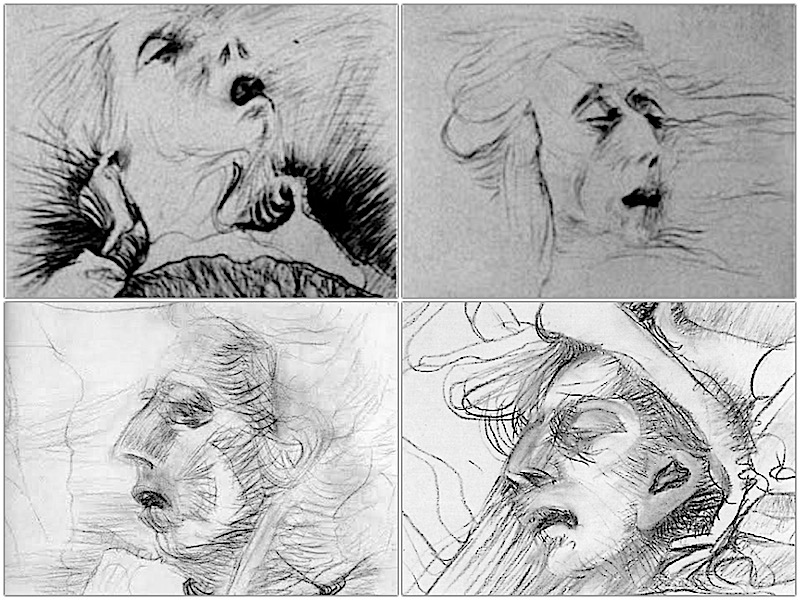

Flávio de Carvalho, “Série Trágica – Minha Mãe Morrendo”, 1947

On its side, the Storefront for Dissident Bodies is host by daadgalerie: clothing and apparels are like a second skin, protective shields, and elements of resistance. The film Resilience Tlacuache (2019) by Naomi Rincón Gallardo is a fable of bastardised Mesoamerican myths, where four characters of different origins and times meet. In order for the tlacuache to share her tricks to play dead and resurrect in extractive areas of Oaxaca (Mexico), they summon the powers of fire and partying by singing and dancing in glamorous lo-fi outfits that contrast with the colours of nature. Celebration, intoxication, and discontent of traditional Oaxacan communities and their mythical conception of territory as a space of communal harmony between natural resources, territory, and people.

Naomi Rincón Gallardo, “Resiliencia Tlacuache”, 2019. Instalation view. Courtesy of the artist. Foto: Silke Briel

The system cracks on the inside

The conceptual thread running through the chapter host at Gropius Bau takes the museum as another patriarchal structure in need of critical review. Entitled The Inverted Museum, includes generous installations that fuse sensitive experiences and intellectual engagement.

The installation Ego Fvlcio Collvmnas Eivs/I fortify columns (2020) by Bolivian artist Andrés Pereira Paz, commissioned and co-produced by the biennial, is a landscape of minimalist sculptures that occupy the floor, walls, and ceiling of a darkened gallery. The song of a bird resonates throughout the space. It is the sound of the Amazonian bird guajojó. When their habitat was devastated by catastrophic fire last year, a single specimen managed to fly to extraordinary heights to find shelter in La Paz, Bolivia, where its sighting became a local sensation. This guajojó seeks asylum rather than migration, it has no home to return to. Pereira Paz, uses the bird’s tenacity as a metaphor for the contemporary collective trauma of migration and displacement, in which escape is exceptionally hard and return often impossible.

Andrés Pereira Paz, “Ego Fvlcio Collvmnas Eivs”, 2020. Instalation view. Courtesy of the artist; Crisis Galería, Lima; Galería Isla Flotante, Buenos Aires. Foto: Mathias Völzke

Replicating the logic of a European anthropological museum, the work The Museum of Ostracism (2018) by Sandra Gamarra Heshiki represents anthropomorphic pre-Inca and Inca ceramics from various museums in Spain —coming from donations and colonial looting. The ceramics that seem to float mysteriously in the air are arranged behind glasses in orderly rows. Walking through them, the objects are revealed as trompe l’oeil paintings, on the back of which are inscribed words used to pejoratively designate the indigenous peoples of South America, a genealogy of prejudice that extends from the conquest to the present day. The exhibition of non-Western objects in different European anthropological museums shows the persistent Western drive to objectify and classify the “others” by revealing the geopolitics of a world still shaped by the colonial matrix.

Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, “El Museo del Ostracismo” (detail), 2018 © Foto: Haupt & Binder

Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, “El Museo del Ostracismo” (detail), 2018 © Foto: Haupt & Binder

The Crack Begins Within is a call for change throughout the global world, proclaiming that breaking with old structures begins with individual responsibility, without neglecting the dangerous potential this holds. The crack is open, dissent is real, and mutates like the virus that contaminates us today.

(Imagen destacada: El Palomar, Schreber is a Woman, 2020. Instalation view. Foto: María Muñoz)

María Muñoz-Martínez is a cultural worker and educator trained in Art History and Telecommunications Engineering, this hybridity is part of her nature. She has taught “Art History of the first half of the 20th century” at ESDI and currently teaches the subject “Art in the global context” in the Master of Cultural Management IL3 at the University of Barcelona. In addition, while living between Berlin and Barcelona, she is a regular contributor to different media, writing about art and culture and emphasising the confluence between art, society/politics and technology. She is passionate about the moving image, electronically generated music and digital media.

Portrait: Sebastian Busse

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)