Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The Bauhaus anniversary calendar of approximately 600 events in Germany reveals a kaleidoscope of versions about this unique interdisciplinary movement which altogether may convey the only fact that there no such thing as one Bauhaus. The prominent sites of the national celebration are Weimar, Dessau and Berlin because here s where the history of the modernist arts-and-craft movement with global repercussion unfolded between 1919 and 1933. It moved from Weimar to Dessau, and finally to Berlin, where the National Socialist party put a harsh end to Germany’s most important cultural export.

Today the Bauhaus is likely to be reduced to exclusive modern design and the pioneers of modernist architecture, therefore to white cubic houses, flat roofs, minimalistic and luxurious design of tubular steel furniture, to all kinds of household accessories with a touch of rationalistic industrial aesthetics and made of exquisite materials. But the original intention of the interdisciplinary movement, which received its important impulse from antimilitarist and pacifistic manifestoes after the horrors of Word War I, pleading for a new society and formulated by many German intellectuals and artists, was quite the contrary. Walter Gropius, founding father and promoter of the Bauhaus idea, was most influential in the innovative concept embracing practical education, a fusion of craftsmanship, technology, collective work and, last but not least, the synergy of craftsmanship, fine and performing arts. Most of all, however, Bauhaus was a Hochschule für Gestaltung – a school in which architects, artists, musicians and teachers – especially in its early years – dedicated their commitment to a mélange of utopian thinking and practical programmes.

To mention a few of the leading figures who represented the contrastive trends, besides Gropius, we should speak of Oskar Schlemmer, who was in charge of theatre and the fine arts, Johannes Itten, who represented the more esoteric-spiritual line within the movement and was quite a contrast to László Moholy-Nagy, who expressed his leftist leaning by constantly wearing a worker’s outfit. The red Bauhaus members, among them the second Bauhaus director Hannes Meyer, finally left the German centre for Russia where they expected to find architectural projects closer to their ideological affinities. The remarkable and unique globalization of the ideas behind this interdisciplinary experiment, however, took place at a high price: as is known, Hitler’s regime forced the politically inacceptable Bauhaus members, especially the Jewish, into exile. This is where many of them spread the Bauhaus visions in their new homelands. Moholy-Nagy founded The New Bauhaus in Chicago. In Israel, the Bauhaus fused with Mediterranean forms. The research project and grand exhibition entitled bauhaus imaginista, held in Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt and organized in collaboration with Goethe Institutes worldwide, has just begun to reflect this remarkable internationalization of the Bauhaus. Furthermore, some Bauhaus100 activities will focus on certain forms of marginalization like that of women within a male-dominated Bauhaus. Ise Gropius, wife of Walter Gropius, was trained as a journalist and worked as his secretary, but Marianne Brandt was the only woman who managed to be accepted by the Bauhaus metal workshop. Normally, female Bauhaus members had no choice but to join the textile and ceramics workshops.

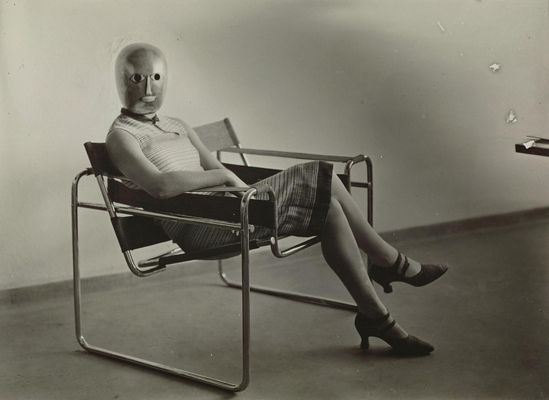

Woman sitting in the chair B3 by Marcel Breuer, Mask by Oskar Schlemmer, Dress by Lis Beyer

Bauhaus100 is finally highlighted by three architectural projects, in the literal sense of the German term: Bau (to build or the building) and Haus (house). In September a new museum dedicated to the Bauhaus will open in the centre of Dessau, built by the Catalan architecture office addenda (González Hinz Zabala), whose design has won the competition for its construction among a total of 831 proposals. The plan to inaugurate two other Bauhaus museums during this anniversary year will unfortunately not be accomplished either in Weimar or in Berlin: the opening in Weimar is scheduled for next year and that of Berlin has been postponed sine die.

(Highlighted image: Building of the Bauhaus, seen from Southwest, Walter Gropius, Dessau, 1926)

Uta M. Reindl, * 1951 in Cologne. Free-lance critic, curator, translator based in Cologne. Regular publications in magazines/dailies, mainly for Kunstforum International; catalogues; edition of two books – focussing also on contemporary art in Spain; curating joint-ventures of artists with students (1996 – 2010), art in public spaces (2001), in galleries (1999/2012); organizing the regional critic platform „Kritisches Rheinland“ since 1996.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)