Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

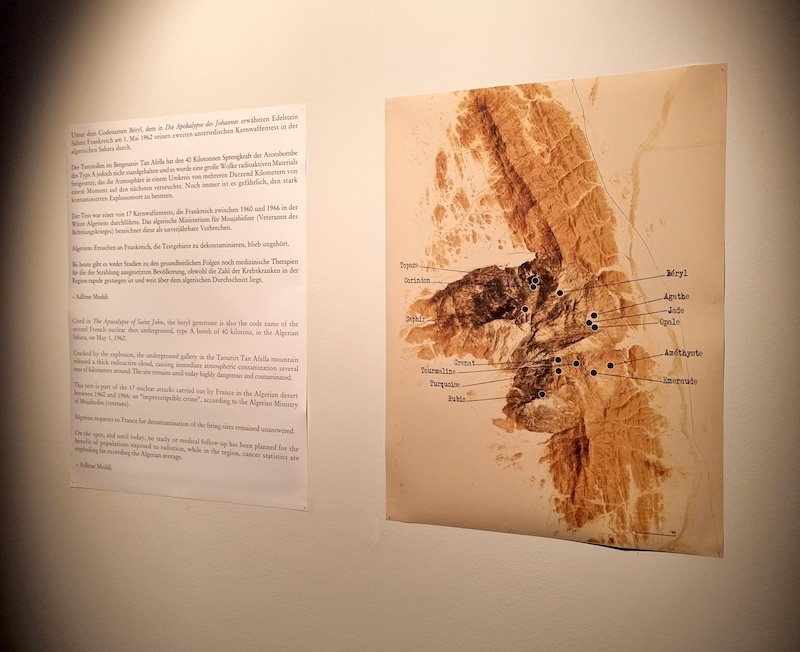

In 2021 on the French-Swiss border, a laboratory connected to the NGO Acro found elevated levels of radioactive particles in the air. Although not found in concentrations that posed urgent risks to health, these particles were the shadowy remains of colonial crimes that France has yet to be held accountable for. In the 1960’s the French government conducted a series of nuclear tests in the Algerian Sahara. These atmospheric and underground bombardments were carried out in what France perceived as an empty territory with utter disregard for the indigenous people who inhabit the desert. Artist Ammar Bouras went to the area nearby the Béryl incident at Tan Afella mountain. There, local testimonies recall how the fallout of the explosions poisoned their bodies and that of their livestock. Algeria still suffers from elevated cancer rates as well as birth defects, and in his work, Bouras reflects on geology and landscape in relation to the health of the body and time. As the desert expands northwards and heat waves increase in intensity, the radioactive particles from the desert fly across the Mediterranean to remind Europe time and time again of the unresolved crimes that lie beneath the silence.

Ammar Bouras

The curator of the 12thBerlin Biennale Kader Attia has built the theme for the biennial around topics which have been at the core of his own artistic work. Recognition and repair are necessary in Europe to begin the process of healing societies ravaged by the unresolved crimes of colonialism and fascism. Having studied at the Escola Massana and being active in Barcelona with a recent solo exhibition at the Joan Miró Foundation in 2018, Attia’s premise opposes the idea that fascism was defeated in Europe by the allies in WWII, a belief still widely held in the North of Europe and North America, which ignoes the existence of Spain, Portugal, Greece and the East. It is connected with the critique by Césaire and Fanon who relate fascism to colonialism and the ongoing extraction and imperialism of the West over the world. As an incoming co-director of the PEI at MACBA, this gives hope that the themes of the biennial will continue in the context of Barcelona which urgently needs a reckoning with the wounds of its fascistic past as well as its colonial reality.

Titled “Still Present!” the exhibition aims to visualise the invisible and to highlight decolonial aspects of ecology and feminism. However, this is achieved through the use of traditional biennial structures without offering strategies for change. Organised across six venues in Berlin, the exhibition is organised thematically with KW focusing on feminisms, AdK Hanseatenweg on ecologies, while other venues highlight historical and present wounds and scars across the Hamburger Bahnhof, AdK Pariser Platz, Stasi Museum, and the center for Decolonial Memory. Beside excellent artworks and a well executed exhibition, loom thematic contradictions including the absence of any clear measures to address the environmental impact of international exhibition-making. The Western biennial model is appropriated by Attia to shine light on new practices, yet we are left with the question of whether this simply serves to replicate extractive models rather than confront the institution with its own hierarchies.

Some of the strongest works in the biennial specifically highlighted individual artists who have not yet gained the recognition from Europe that they deserve, alternative discourses (such as the added social complexity of caste in India), or unspeakable subjects such as rape as a historical and present war crime against women. In the first category, Tuan Andrew Nguyen presents two film-installations that take over space with their poetic narratives. My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires(2017) is a dialogue between the last Javan Rhinoceros and a sacred turtle. The discussion between members of the animal world pronounces all of the unspoken violence done through various colonialisms onto nature and its non-human inhabitants. In Specter of Ancestors Becoming(2019) Nguyen films members of the Vietnamese community in Senegal who travelled there following marriages to Tirailleurs Senegalais who served in the French military against the independence of Indochine. Colonial processes tie together very different parts of the world that were brought together for violent motives and in turn produced families and love stories across the world.

Prabhakar Kamble

In the Hamburger Bahnhof, Birender Yadav presents shoes of Indian migrant workers of the lowest caste. Their social status prohibits them from acquiring legal documents that would prove their existence and they are condemned to working in highly exploitative conditions and in extreme heat. In the work of Prabhakar Kamble there is a similar focus on the feet of workers which prop up sculptures including cult symbols of a cow – considered more valuable than humans – to describe the unique caste problematics in South India. Mayuri Chari’s I Was Not Created For Pleasure (2022) describes these complexities from a feminist perspective by denouncing the appropriation of colonial censorship of the female body and the rewriting of tradition which formerly openly depicted nudity and now regularly prohibits it in art.

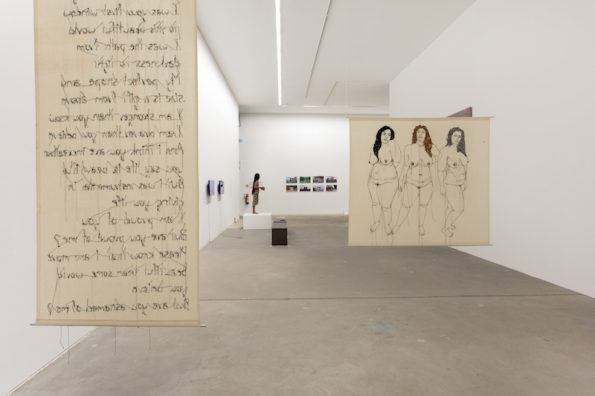

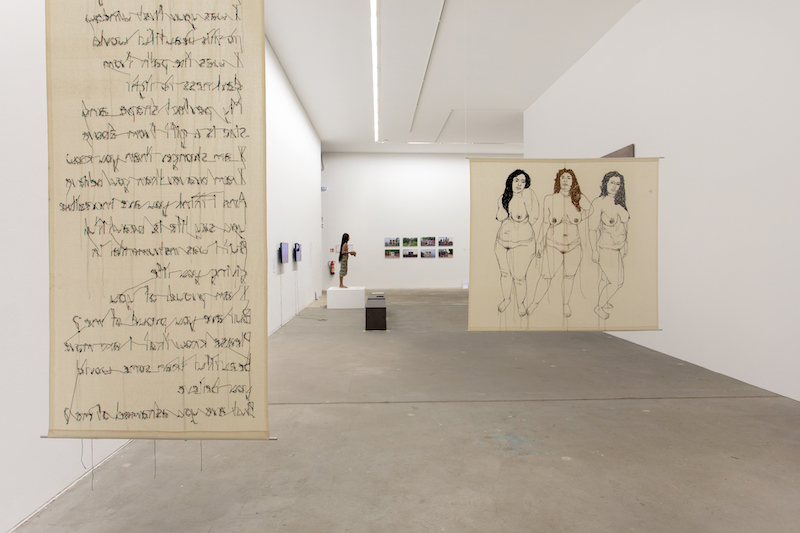

Mayuri Chari

A chilling work by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay denounces the continuing silence around rape as a weapon of war. Berlin was left a charred and broken city after the end of the second world war, but the war against women continued for years. Across national boundaries and political banners, accounts of how rape and sexual abuse were used against women in a devastated city continued after the allied takeover. A few floors up, a photographic report by Etinosa Yvonne brings contemporary accounts of women kidnapped and forcibly married alongside the continuous warfare of Boko Haram in north-eastern Nigeria and the lifelong effects of these events that remain with the women and scar these regions.

The works mentioned above are harsh reminders of silent oppressions, they are sensitively constructed through reflections on authorship and belonging. A few works in the exhibition seem to clash with the principles of the biennial and revert to colonial orders of representation. In the center of the Hamburger Bahnhof, a strange moment arises in which two works stand out in jarring contrast to the aesthetics and sensibility of the rest of the biennial. One installation by Jean-Jacques Lebel appropriates the famous pornographic images of tortures conducted by the American military in Iraq blown up into labyrinthic proportions. The nauseating proximity of these images are the desired affect of the artist described as a malaise. Nearby, an installation by Zach Blas is a science-fiction based account of AI recognition of emotion. An interesting work in itself, it awkwardly introduces a vast topic which is not explored further in the biennial. There is a rare mention to the categorization of queer communities which is welcome, but which also comes from the perspective of the global North which sticks out against the surrounding works. The lack of contextual support creates a strange aesthetic component to the biennial and as a piece that has been left to carry the burden of this enormous subject alone.

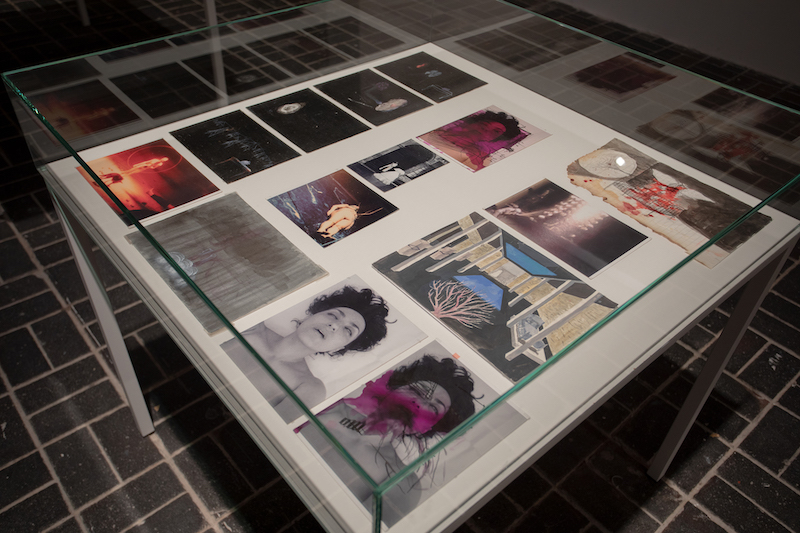

Amal Kenawy

Ultimately, the aim to show unheard voices using the traditional biennial format as a podium to uplift these perspectives is effective, but it loses its strength when they are positioned next to such famous and overexposed collectives as Forensic Architecture who have held major solo exhibitions throughout Europe. A gesture is made to include a new video by the collective about Ukraine, but it is formulaic in its execution and only serves to highlight the lack of Ukrainian artists in the biennial. I’m left with the feeling that nearly 35 years later, we are still looking at the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre (Centre Pompidou, 1989) which proposed to organise a “world exhibition” in Paris curated by a team of French and British curators. The curators are now selected from more varied experiences and locales, but aren’t curators (or in this case, artist-curators) the new artists in 2022? The structure remains the Western one and a feeling persists of being stuck in a rut. Ever greater atrocities and hidden realities are revealed before our eyes while no options are laid out to exit the system that has made these destructions our lived reality. And every day we breathe it in, the violence, stories, and radioactivity keep accumulating without ever properly being healed.

The School of Mutants

Berlin Biennale 2022 – Still Present!

11 June – 18 September

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)