Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

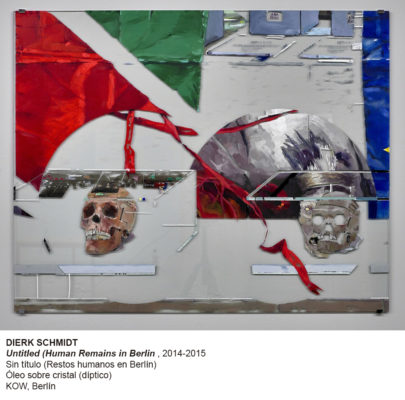

Dierk Schmidt who presents himself at the Palacio Velázquez in Madrid is an activist who hunts the ghosts of the colonial era. The silent and muzzled conscience of Europe of human and cultural genocide, materialized in a weightless and forensic way on glass and plastic.

No one is better as a support and logistics team than the commissioner who militates between the political compromise and the phantasmagorical attraction: Lars Bang Larsen. The curator proposes a clean staging and unusual but effective solutions, favouring Schmidt’s direct and spectral discourse. In “Guilt and debts” works generated from the 90’s to the present day, installations and mixed techniques of which contents and continents refer to the use and abuse during the colonial and post-colonial era by European countries (with the artist’s native Germany as the protagonist) towards African countries are dispersed. In “Untitled (Human Remains in Berlin)” (2012-15), an oil painting on glass, two Skulls are shown in the foreground, enclosed in showcases suggested with slight lines of colour, and a perspective in flight leads us to a museum structure. The material presence of both skulls (one of them with empty eye sockets, without paint, superimposed on another, crowned with feathers), floating on a transparent surface, turns the work into a spectral apparition, almost an incarnation. And they are neither spectra nor decorative skulls, nor even pieces of historical or archaeological relevance: they are human remains. The artist declared to the press that he is part of the collective “Artefakte/anti-Humbodt”: “Since we have made possible the return of a score of skulls to Namibia that were in Berlin and they are the result of the extermination that the German State carried out at the beginning of the 20th century against the citizens of Nama and Herero. Those remains were subjects, with names, they became objects when they entered a museum now they have recovered their status as subjects when they were returned to their land”. In his work of invocation/convocation, Schmidt therefore does not repeat the colonialist equation and turns the targeted into a new (art) object, but accompanies an active and activist work of physical and moral devolution. And he knows that the best way to solve the duopoly that gives title to the exhibition, to shake off those faults and those debts, is to reveal the root of the problem. In his series “The Sharing of the Earth” (2005) he points to the division of the African continent by European countries at the Berlin Conference of 1884. And it does so with the same coldness and technicality with which they drew lines on a map: with diagrams and chromatic codes. The consequences of arbitrary distribution were exhibited in museums in Europe, proudly filled with plundered objects and creations. Dierk Schmidt exposes the operative with series like “Broken Windows” (2013-in progress), showing the support, sometimes pierced, as trace of the looting. Process of cultural dismantling that continues today as exemplified by his work on the BP oil company or the museum of world cultures by Germany, using an 18th century imperial palace, renamed as Humbodt Forum, as home. Regarding the exhibition spaces, one regrets that the nearby Palacio de Cristal in Madrid, created in 1887 on the occasion of the Exhibition of the Philippine Islands, was not used for this exhibition, although in the Palacio Velázquez there were also exhibitions associated with that event, result of the worst colonialism. The glass vault of the former would have favoured the translucent experience of “Guilt and Debts”, the stripping of the bas conscience. The link with Madrid established by Schimdt is achieved with “Focus on a Showcase concerning the Archaeologist Julio Martínez Santa-Olalla”, a specific project for the exhibition, which recalls the work of the Spanish archaeologist who stole thousands of pieces from the Sahara during the 1940s. Santa-Olalla is the last ghost conjured up in this exhibition of exhibitions, this haunted house which is, if one reads between the lines, the history of modern Europe.

View of the exhibition DIERK SCHMIDT. Guilt and debts, in Palacio de Velázquez. October, 2018 Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia

Image: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores. Photographic archive of Museo Reina Sofía

His intention is to continue to improve his writing of art criticism; everything else is enjoying and learning from contemporary proposals, establishing other strategies of relations, either as a contributor to magazines, editor of a review, curator or lecturer. As a backpacking art critic, he has shared moments with artists from Central America, Mexico and Chile. And the list will continue. Combating self-interested art, applauding interesting art.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)