Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Douglas Coupland, author of Generation X (1991) and Generation A (2009), is best known as the man who can see the future. A couple of years ago he proclaimed to an audience: “Until recently the future was something that awaited us. It was something we anticipated and even feared. At one point the present merged with the future. Now we are living inside the future permanently. It’s what I call the super-future.”

Like the philosopher Paul Lafargue (The Right to Be Lazy, 1883), Coupland believes that a 9-to-5 workday is old-fashioned and something to be prohibited, like child exploitation. In his manifesto in favor of laziness, Lafargue argues that the modern machines of the Industrial Revolution were supposed to give human beings more freedom. Lafargue: “But what happened? As the machine perfects itself and replaces human labor with ever greater speed and precision, the worker, instead of increasing his rest by the same amount, must double his effort, as if to rival the machine.”

The revolutionary Lafargue, enemy of overproduction, proposes a workday of a maximum of three hours, “lazing around and enjoying the rest of the day and night.” In his regime of laziness, to kill the time that kills us each second, there will be permanent spectacles. By the end of the 19th century, Lafargue was already imagining a world of “Netflix and chill.” Imagine Lafargue’s reaction if he had known that the Digital Revolution and artificial intelligence in the 21st century would give us more freedom, although we continue to work a full 40-hour week.

Back to Coupland. The Canadian artist works with artificial intelligence. Last year, a team at Google fed all of Coupland’s literary work from the last thirty years into a computer through an automatic learning algorithm. The machine became familiar with the style of the writer by consuming more than a million of his words. The computer was then fed another million words taken from Instagram posts on how to create short and inspiring sentences. With all this information, the artificial intelligence created twenty-five slogans inspired by Coupland’s texts. As the artist himself commented: “Have I written these sentences? Yes and no. Could they have existed without me? No.”

For over ten years Coupland has been working with the format of slogans, which compress the greatest amount of information into the least amount of words. For him, this is an exercise in discovering the collective sensations of our world culture. Coupland was inspired by the work of the artist Jenny Holzer who at the end of the 1970s began to exhibit her Truisms in public spaces, with statements such as “Work is a life-destroying activity,” “Any surplus is immoral,” or “The redistribution of wealth should be mandatory.” As Holzer commented in an interview following her exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao in 2019: “There are truths that are so obvious it is painful to remember them.”

One of the slogans that Google’s benevolent artificial intelligence created from Coupland’s futuristic ideas was: “In the future we will all be the 1%.” This phrase painfully underlines the growing inequality in society. As best said by the economist Joseph Stiglitz, in the world in which we live “the 1% of the population has what the 99% need.”

In Coupland’s super-future, office jobs are dispersed and the workday becomes more fluid thanks to the cloud and the higher speed of our Internet connection. Our work hours decrease, and every day of the week feels like a Wednesday. There is no weekend to look forward to, nor do we suffer from Monday blues. Blessed be Wednesday.

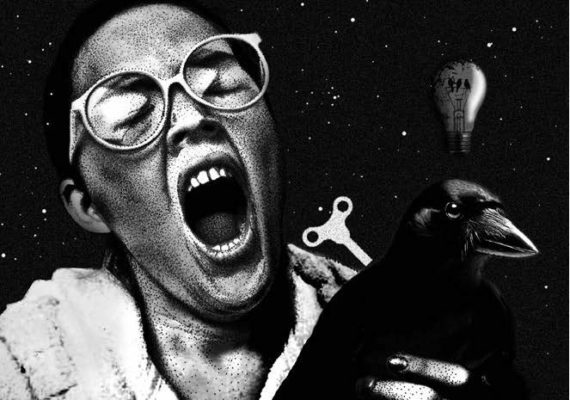

(Featured Image: Illustration by Pilar Sánchez Molina for “El derecho a la pereza” [Yhe Right to be Lazy* by Paul Lafargue (1883), Published by Virus, 2016)

After finishing his studies in Cultural Anthropology at the University of Leiden (The Netherlands), Ferenz Jacobs (1982) moved to Barcelona to take a postgraduate course in Contemporary Art Theory at the Fundació Joan Miró. He gained experience at the Metropolitana gallery, the Loop fair and the Mecal festival and curated several exhibitions on cannabis culture at the Hemp Museum in Barcelona. At the same time he published essays and articles on video art and counterculture. He currently enjoys visiting art stores, exploring the border between what is shown and what is hidden.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)