Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In February last year, just a few weeks before the current global pandemic kept us on tenterhooks until the present day, the director of the Mars 2020 programme announced on camera the landing of the rover Perseverance on the Jezero crater on its desert surface. This historic event has once again encouraged humanity to observe itself in the inverted mirror of its neighbouring planet.

Because of its physical similarities, since the earliest records by Egyptian astronomers in the 2nd century BC, Mars has been the repository of our innermost fears and anxieties (will it harbour Earth-threatening life forms?) and, in recent times, heated expectations (will terraforming be possible?). If promises of prosperity and wealth drove the European colonialist spirit from the 15th century onwards, what are the motives today? Mythology, popular culture and science triangulate a representation of this astronomical object: the latest promise we look longingly at the Earth. With expectations to know if there is, was or will be any manifestation of something like life, if it can become a plan B. Will it be?

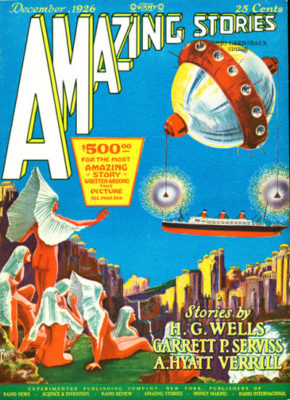

But will we be able to know it without conquest, without colonisation, without the historical violence that scientific progress itself has paradoxically encouraged? These and other questions lie in this exhibition curated by Juan Insúa, director of the CCCB Lab. Mars. The Red Mirror proposes a triangulation between its representation as the god of war but also of harvests, to its paranoid omnipresence in the pulp era of science fiction and as a terrain for sizing up the future effects of the progressive desertification of our planet in the Anthropocene.

From its various archaeological traces in everyday objects and sculptures in the Balearic Islands thousands of years ago as Mars Balearicus, a symptom of the warlike and mercenary culture of its ancient inhabitants, to its early records and its privileged place in the Ptolemaic geocentric system, which can be seen in the ancient cosmography books on display, the seeds of the red planet grew assuming different forms in an age where science and myth flourished together. Considering the Divine Comedy as a work of proto-science fiction, even its reference in Shakespeare’s Henry V as a “fiery muse”, the journey of Mars in this exhibition also leads us to the history of its misunderstandings, such as the “grooves” discovered by Schiaparelli in the 19th century which, due to a translation error, were conceived as “canals” and attributed an artificial construction. Thus we arrive at the 20th century where science fiction populated our imagination with invasions, monsters and little green dwarfs.

However, one of the most enduring pieces from this period of the rise of so-called fan-science is 1950’s Martian Chronicles, where the planet is the inverted mirror of Earth, reflecting its own moral dilemmas in the face of racism and war. In this same line of elegy and melancholy tone, one can see a fragment of Blues for a Red Planet, by Carl Sagan, as well as the production conditions of the trilogy dedicated to him by the writer Kim Stanley Robinson, inspired by the desert of Sierra Nevada and the sublime landscape of Antarctica. Towards the end of the exhibition, current projects in different space agencies can be seen facing each other in the same corridor, like an inverted reflection, with suggestive projects of speculative imagination.

From the epic deed to the elegy, from the war song to the blues, from medieval reverie to objective and truthful representation, from the astronomical precision of modernity to the fear and paranoia of the 20th century to the current expectations on Mars. The Red Mirror shows how it encouraged scientists, writers and artists from different eras. From optical illusion and mirage to the presumed specular precision of science, halfway between objective description and fevered fantasy, Mars appears in this exhibition tour with great didactic forcefulness, vertebrated in the multiple fragile edges that construct it in the past, present and future of our collective imagination.

(Featured image: Amazing Stories, vol. I, núm. 9. Cover illustration by Frank R. Paul. Gernsback Publications, december 1926. © David Saunders Collection)

Ana is fascinated to dive into books and movies, to approach with caution those tentacles that lie in the depths and to return to count what she has seen. She has published “Este es el momento exacto en que el tiempo empieza a correr” (Premio Antonio Colinas de Poesía Joven), the novels “La puerta del cielo” and “Hemoderivadas”, “Constelaciones familiares” (short stories, Premio Celsius Semana Negra de Gijón) and “Érase otra vez. Contemporary fairy tales” (essays). She currently lives and works between Berlin and El Paso, Texas, where she is a Bilingual MFA Fellow in Creative Writing at UTEP. Some of her texts have been translated into Portuguese, Italian, Polish, Lithuanian, German and English.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)