Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The 21st century has given us some of the most remarkable encounters between design and technology. Few fashion shows in this regard are as memorable as Alexander McQueen‘s Spring/Summer 1999, where the designer began to showcase some of the early scenarios of convergence between these two disciplines, and the (not so) incipient threat of the technological – something that would be evoked once again in his final catwalk Plato’s Atlantis (2010).

Certainly, this is not something that only began in the late 20th century, as the relationship between fashion and technology has always been close: design is certainly always linked to it. Think of designers like Pierre Cardin and his incorporation of plastic and sculpturality in the 1960s. Similarly, in the early 2000s, the initial runway presentations of Turkish designer Hussein Chalayan revealed a clear interconnection with different levels of technology that would increase in the subsequent years. Both examples illustrate how what we now remember as low-tech has always been connected to clothing.

Iris Van Herpen, Snake Dress (2010), Dewi Driegen by Duy Quoc Vo for V Magazine Online

On this occasion, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris proposes an exhibition titled “Sculpting the Senses,” dedicated to the fragmented universe of Dutch designer Iris Van Herpen, with a focus on her haute couture work.

Despite these precedents, Van Herpen’s style is different; her vision for the future is at a surgical level. Her aesthetic approach borders on asceticism, showcasing a visual purity that reflects a deep exploration of the most contemporary architectural language. There seems to be no place for the rawness of certain organic materials, and it is from this desire that the synthetic verses dedicated to water, and wind emerge.

This approach not only limits itself to technique and execution based on parametric architecture, characterized by its fluidity, fragmentation, and changing patterns but also extends to the conceptualization of her creations. Van Herpen is known for her ability to draw inspiration from diverse sources, leading to captivating results, and exploring avant-garde themes that go beyond the traditional conventions of fashion.

Iris Van Herpen, Quaquaversal (2016). Photo: Morgan O’Donovan

However, the operating room is mainly dark – another flaw in the museography – the designer is presented to us as an enigma, whose creativity will only be accessible through a process of semiological recognition as if replicating a reverse engineering process.

The proposed curation exposes us to the designer’s work, juxtaposed with various objects of art and design, attempting to explain the sources of inspiration and where the relationships with the designs presented there emerge. In this solipsistic process, all historical antecedents, such as the works of Hussein Chalayan or Alexander McQueen (with whom the designer took her first steps), are eradicated.

Iris Van Herpen, Cathedral Dress (2012). Photo: Morgan O’Donovan

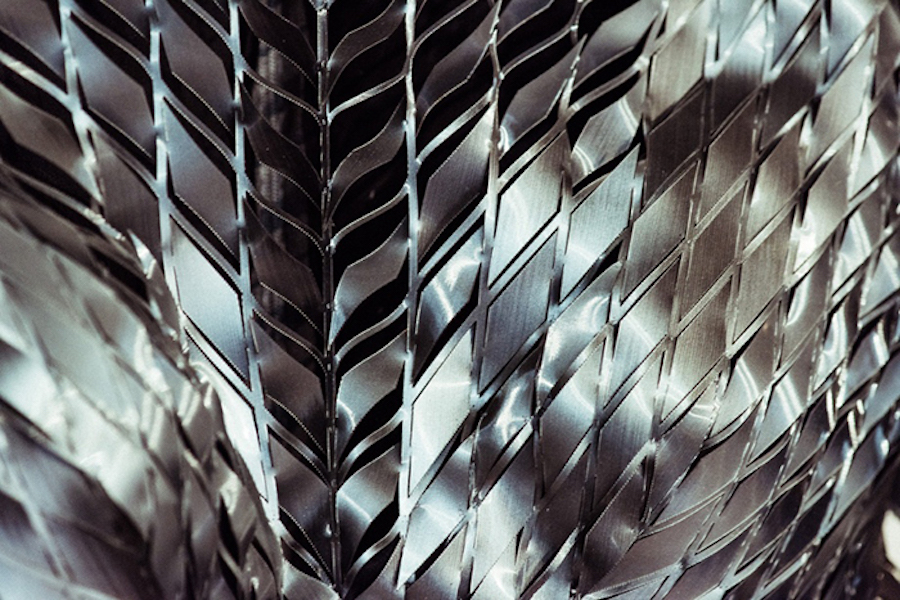

The sculpture “Nautilus Penta” (2023) by the Belgian Wim Delvoye, where (as is customary in his style) Gothic cathedrals are used as minimal units, overlapped (and in this case) twisted to replicate the shell of this mollusk from which it takes its name, is juxtaposed with the “Cathedral Dress,” presented in the spring 2012 collection, where a similar process is carried out, perhaps being one of the most linear relationships in this effort to point out possible influences.

Throughout the exhibition, there is an attempt to desensitize the viewers, a quest to intoxicate the senses, altering perception with a disturbing sound installation: an attempt to materialize a synesthetic effect, referring not only to Van Herpen’s condition but also to the themes of her seasons “Seijaku” (Fall/Winter 2017), where she explores the aesthetic potential of cymatics, studying the visual evolution of sound waves as geometric patterns, and “Sensorie Seas” (Spring/Summer 2020), where the neuroscientific theories of Santiago Ramón y Cajal and his structural drawings of the nervous system converge with patterns presented by different types of cnidarians and mycelium.

Iris Van Herpen, Roots of Rebirth (2021). Photo: Myrthe Giesbers

Considering precisely the dynamism and vibrational sensations evoked using the garments, the decision to almost eliminate movement in the exhibition of the pieces is quite controversial – from a museographic perspective – clearly, this is their sine qua noncondition.

Certainly, this self-moving dimension is essential from the inception of her work, as can be seen in designs from her Spring/Summer 2010 and reflected in the sculptures of Kate McGuire and Juliette Clovis.

Iris Van Herpen, de Hacking Infinity (2016). Photo: Morgan O’Donovan

This weightless character is essential in Van Herpen’s work, where a prolific oceanic style can be recognized. References such as the silhouettes evoked by Alexander McQueen in his aforementioned “Plato’s Atlantis” show indicate that the aquatic relationship is not the only one of interest to the designer but any anti-gravitational relationship, any dynamism of form related to challenging entropic conceptions (in a strictly physical sense). This contrasts with the rigidity and heaviness of other design that reference processes of crystallization and fossilization.

Between Music group performance during catwalk Aeriform (2017). Photo: Morgan O’Donovan

Van Herpen’s work is undoubtedly a synthetic universe of convergence between the forces of nature and cultural pressures, reorganizing and rearranging codes and social orders in a style where crinoids and ruffs can copulate to give life to an intricate artificial mesoglea[1]The mesoglea is the mainly watery tissue that serves as a hydrostatic skeleton in animals of the phylum Medusozoa (jellyfish).. A symbiosis of high technology and haute couture craftsmanship appears in embroideries reinterpreting mycelial patterns.

In the development of three-dimensional appendages, even coated in latex to mimic the skins of mythological animals, cochlear shapes, and liquid metals, the subjects created by Iris Van Herpen are cyborgs of distant bodies. Virtual boundaries are evoked in a pulsating centrifugal fascination, from which sensory barriers are ejected. This virtuality functions as a holographic, mutable boundary, both technological and biological: a limit that can be there and be an embrace as well as a weapon.

The exhibition “Iris Van Herpen: Sculpting the Senses” is in display at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris until April 28, 2024.

| ↑1 | The mesoglea is the mainly watery tissue that serves as a hydrostatic skeleton in animals of the phylum Medusozoa (jellyfish). |

|---|

Gonzalo Pech [Argentina] is an unstructured text characterized by a narrative that is at times excessively analytical. His work, which transmutes between the philosophy of art and advertising since his adolescence, is full of irreverence and contradiction. Curator and photographer by training, he has preferred to frame his practice in what he calls Blessure D’art, amalgamating its nihilistic yet platonic nature

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)