Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

On January 12, 2024, the first TEA Tenerife Contemporary Biennial came to an end. Over the course of three months, this event provided the framework for profound reflection on the central themes of its first edition: the confrontation with power structures, established dogmas, and historical narratives. Curated by Raisa Maudit and Àngels Miralda, the biennial mapped out a structured journey through artistic projects that, under what they themselves have termed the “heretic proclamation,” addressed questions of colonial inheritance, violence against the land, and identities in constant metamorphosis.

The heretic proclamation invites us to embrace dissonance, ruptures, and the potential for transformation, establishing Tenerife as a space of resistance —both locally and internationally. From this position, led by Raisa and Àngels‘ sharp minds, I allow myself to find a connection with two other thinkers: Judith and Hannah. Butler, in discussing performativity, understands the “proclamation” as a subversive act—a political stance that challenges power structures. Meanwhile, Arendt’s notion of “heresy” aligns with her vision of political action as a rupture from hegemonic narratives, which opens the way to new forms of insubordination. Within this biennial, these ideas converge, questioning established structures and exploring alternative pathways of defiance.

In this context of analysis and confrontation, curating emerges as an exercise in coherence, bridging the site and the narratives embedded in the exhibited works. The exhibition design—a circular journey from shadow to light —was conceived as a visual metaphor for the transition from oppression to liberation. The rooms, distinguished by specific colors, not only articulate distinct thematic lines but also serve as containers of meaning, where the artworks, in their variability, seem to breathe within the room they inhabit. Here, space is not just a frame but a vital, dynamic entity, allowing for circulation and interaction without compromising the autonomy of the pieces or confining them. Thus, the curatorial design does more than organize; it transforms it into a performative act—a place of insurgency in itself, where fractures within dominant narratives become visible through the arrangement of works, walls, and pathways. This exhibition walkthrough was not only an act of conceptual subversion, but also an invitation to critical thinking. Parallel events, screenings, and activations provided a forum for delving deeper into the debates sparked by the biennial, encouraging the public to confront disruptive themes within an insular context marked by colonial legacies. As such, the biennial stands as a beacon of dissidence, challenging power structures and urging us to continue questioning, rethinking, and reshaping our relationship with history, the present, and the future. For this reason, we spoke with curators Raisa Maudit and Àngels Miralda to delve into the curatorial process, the challenges encountered, and the concerns that guided the selection of artists and themes that shaped this edition.

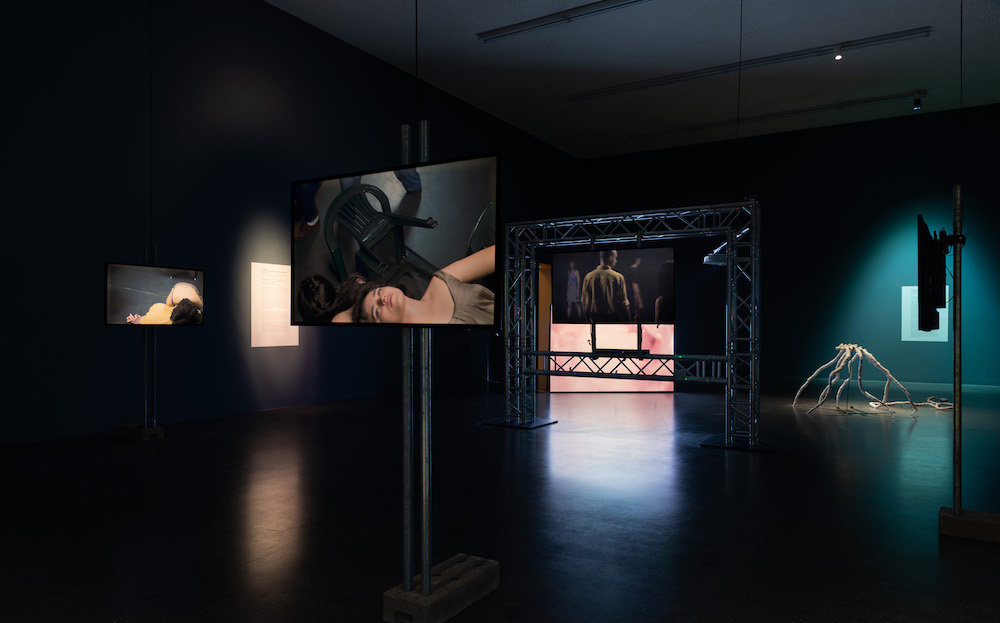

Ezra Šimek, Joyful Flame, 2022

The Process of the Duo Àngels/Raisa

Did you know each other before working together on this biennial? How did the idea of collaborating on this project come about?

The museum proposed the idea, considering our trajectories and curatorial interests as well as our previous experience with the institution. I had curated several projects and, in 2023, directed the Producción 0 artistic research residencies, in which Àngels was part of the jury. The institution sought profiles with extensive experience but also fresh, external perspectives to shape a new biennial that could question itself while maintaining a strong national and international presence. We were the right fit for that.

Could you briefly describe your working methods and how you organized yourselves during the different phases of the biennial?

It was a tough process in a very, very short amount of time, requiring a lot of flexibility, adaptability, and communication. We are “rare profiles” in the system, and we think that helped significantly, as did building a team that was personally committed to overcoming every challenge that arose. It was an incredibly intense process, shaped by wars and grief, and we believe this way of working made everything possible on the ambitious scale we envisioned.

Izaro Ieregui, (Apuntes para) La ira neumática, 2023

How did you merge your personal and professional experiences—Raisa, as a Canarian artist and curator with your project Storm & Drunk, and Àngels, with your hybrid approach between criticism and curation? How did your curatorial approaches complement each other?

Our compatibility was great precisely because of our hybrid profiles: Àngels coming from criticism and independent curation, and me as both an independent curator and artist. We share conceptual and political curiosities, so it was truly beautiful to team up on this project, from conceptualization to production and problem-solving, as we faced challenges from wars to personal grief.

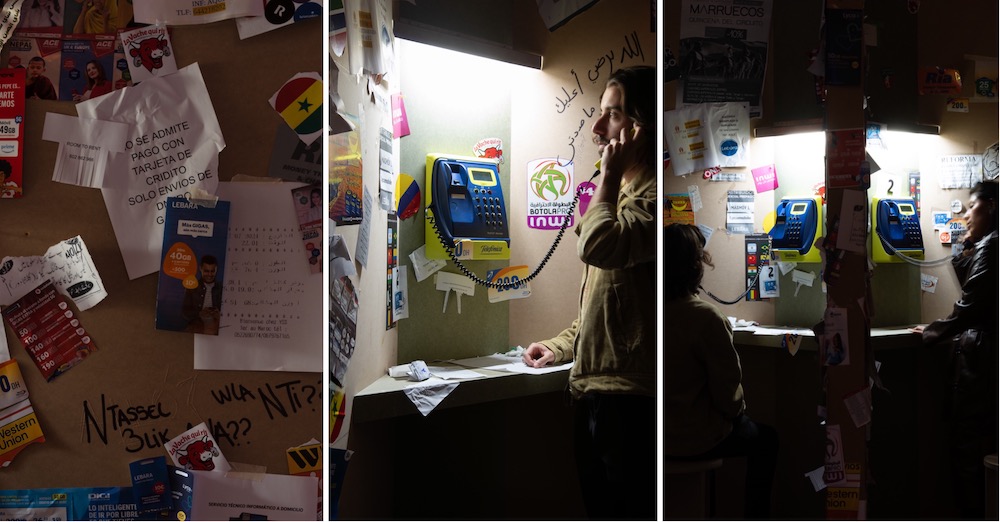

Abdessamad El Montassir, Trab’ssahl, 2024

On the Curatorial Concept

“The Heretic Proclamation” suggests a gesture of opposition and transformation. How did you define the concept of heresy for this biennial, and what criteria did you follow to select the projects that represent it?

The criteria for evaluating proposals were set early in the application guidelines. We were looking for solid projects that could also propose participatory elements, opening up the exhibition gestures to the public. This was important because, from the start, we both and TEA Tenerife wanted to question the biennial format and its relevance, especially given the existence of Fotonoviembre Biennial, which has decades of history.

Once we began analyzing the nearly 1,000 proposals, we started identifying common threads of thought, which translated into the four curatorial lines that, together with the jury, guided the final selection. At that point, it became clear that the selected artists shared concerns that, formally, in their research, identity, processes, and connection to territory, engaged with the idea of alternative paths to classical structures of political power, capital-H History, and established artistic languages.

Within this framework and through our discussions, we began thinking about the archetype of the heretic: someone who, whether deliberately or not, becomes the number one enemy of a system of power. We explored how this archetype has evolved over time, not only from a religious perspective—Christianity, Judaism, and Islam—but also through figures like Pasolini or Simone Weil. Similarly, we embraced the idea of a proclamation to highlight the inherent contradiction of being an archetype of opposition: opposition to what, in what way, and for how long? In this sense, the proclamation functions both as a manifesto of rebellion and as a declaration of law that punishes the archetype of the heretic.

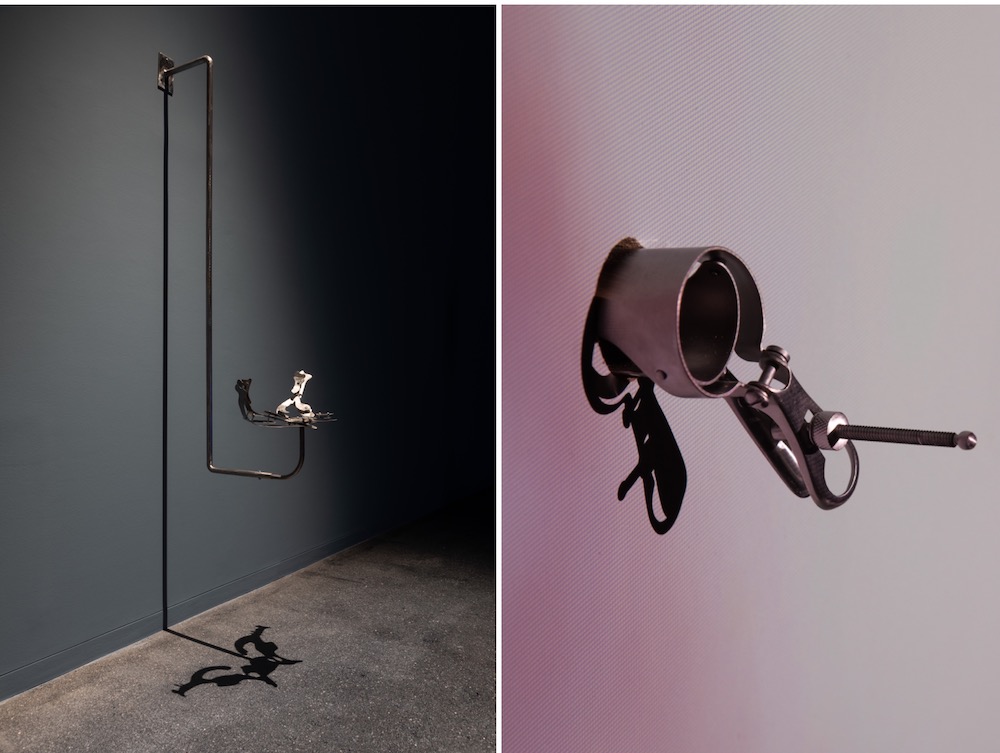

Miguel Rubio Tapia, Ladrido-Corteza, 2024, detalles

What challenges did you face in questioning structures of power from within an institution like TEA? How did you manage to keep the biennial aligned with its disruptive purpose?

We believe that contradiction and difficulty, the possibility of losing control over something, is inevitable and enriching when thinking about disruption. For us, it was important that the exhibition was alive—that it evolved, that certain works decayed over time while others were activated, and that new proposals and references could be added.

This was heavily emphasized in the public program and the audiovisual program FOCUS. We also wanted to break the binary of winners and losers by inviting more artists and agents to contribute to this living exhibition—almost like a Golem—even if their projects didn’t make the final selection.

From a production standpoint, The Heretic Proclamation was an ambitious project that required immense commitment, both in pace and intensity, with activities happening constantly. We were incredibly fortunate that the TEA Tenerife team collaborated with us, making this biennial something unique—like a comet.

Al-Akhawhat, +212, 2024. Al fondo: Laura Mesa Lima, Dos moldes para un constructo, 2017

Tell us about the formal progression of the exhibition (from light to darkness) and the arrangement of the 12 pieces.

First of all, I’d like to thank the installation team and the exhibition designer, Carlos Martín, who were instrumental in transforming the space architecturally and in terms of lighting. It was quite a challenge to design such a complex layout that functioned well, especially given the large amount of audiovisual material in the exhibited works.

The journey began in the Mutable Room, which, in my view, was the most significant. This space acted as both the starting and ending point—a place for reading shifting references, unraveling symbolism to connect with the exhibition, and hosting temporary displays and talks.

From this mutable space, we proposed an exhibition that navigated in a serpentine way through varying intensities, where light, scent, and sound interacted with the physical presence of the audience. It was very important for us to start locally, from a prism of historical rupture, with works like Ladrido-Corteza by the artist from La Palma, Miguel Rubio Tapia, or the Tenerife-based Carla Marzán’s La escuché desde la otra montaña. The exhibition culminated with works that had been suspended in time due to conflicts, such as the war in Gaza and the war in Ukraine, with Uncertain Times (Background from a script) by Lebanese artist Lamia Joreige and Dreams Station by Serbian artist Dejan Kaludjerović, respectively.

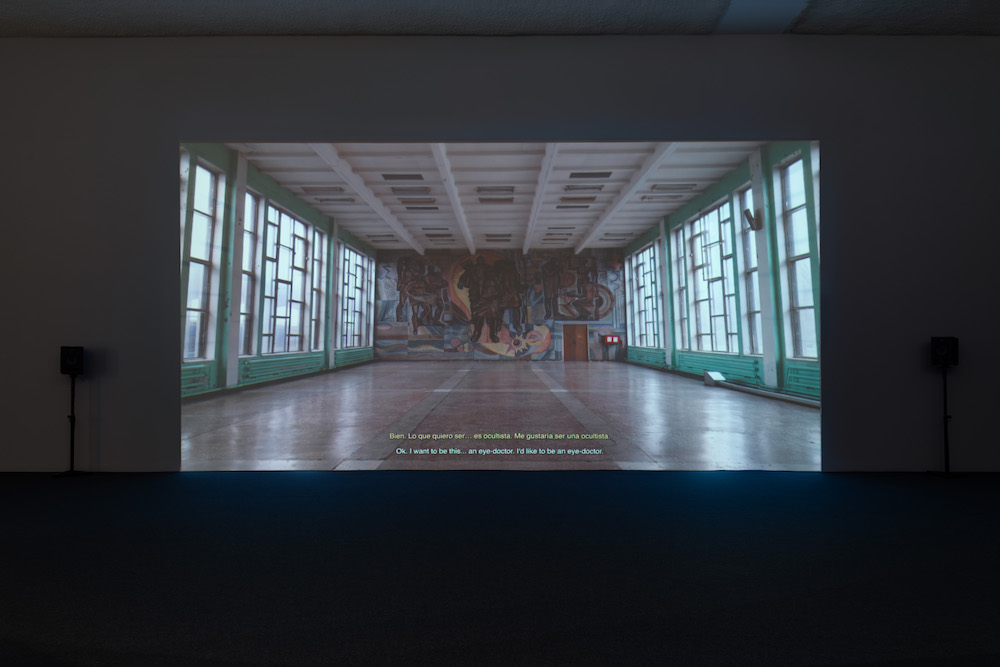

Lamia Joreige, Uncertain Times (Background from a script), 2024

In the middle of this path, we designed a specific journey, which spectators could simultaneously hack and traverse. These interruptions allowed for theory-fiction encounters, such as in Caminhantes by Brazilian artists Victor Leguy, Gabriel Bogossian, and the Guaraní Ariel Kuaray Ortega. Works like Dos moldes para un constructo by Tenerife artist Laura Mesa Lima also contributed to this narrative, alongside participatory, collective creations such as +212 by Al-Akhawhat, which put the subject of migration front and center in a deeply personal way.

Some stories were not told in words, like Trab’ssahl by Sahrawi artist Abdessamad El Montassir, or the works by Canarian artist Maï Diallo (Corpus foramis and Homo vertebrate), where the smell of soap, viscous sounds, and body horror narrate the gynecological violence endured by enslaved Black women. The exhibition also confronted infrastructural terror through Russian demonology with Onset by Anna Engelhart and Mark Cinkevich, both working under pseudonyms as they are persecuted by the Russian and Belarusian governments, respectively.

Fragmented throughout the exhibition was a questioning of gender impositions: the rage and binary identities of cinematic female and male archetypes were transformed in works like Apuntes para La ira neumática by Basque artist Izaro Ieregui or Joyful Flame by Czech artist Ezra Šimek, which unfolded among medicinal and hallucinogenic herbs.

In this way, the exhibition proposed, from a complex prism, the possibility of reading and linking the works in different ways—even within a linear path. It invited immersion in a universe of its own, where the connections I’ve described here (disorderly) could emerge organically.

Sala Mutable

On the thematic narratives

The four thematic narratives of the biennial seem to intertwine. How were these categories constructed, and what connections emerged between the artists and their works?

As we mentioned earlier, these themes emerged during the final stages of the selection process: Tracing Histories, Lineages of the Present; Countercurrent Identities; Rootedness to the Land, Violence to the Earth; and Methodical Transmutations. These lines were present in the artists’ works in multiple ways—most of the pieces navigated between one, two, or even all four themes. This allowed us to play with the choreography of the exhibition, using color codes and symbols that enabled viewers to interpret the exhibition from different perspectives. It almost made it inevitable for visitors to return multiple times, getting lost in the layers and unraveling as many as they could—if that’s even possible.

These connections also worked as a proposal for temporal disruption: thinking of exhibitions as places of seduction or hypnosis that ask for your time but never impose it, instead creating a desire to engage.

Miguel Rubio Tapia, Ladrido-Corteza, 2024

What discoveries or insights stood out after exploring these dialogues among artists from such diverse contexts?

The process of this Biennial was intense and happened on a tight schedule—everything took place within the span of a year. Personally, it was incredibly enriching to work from an open call instead of direct invitations, as it allowed us to discover and dive deeper into artists neither of us had on our radar. It was a profoundly rewarding curatorial experience.

One of the most intense learning moments was facing the onset of the war in Lebanon and witnessing how it affected several artists. We cared for them on both a personal and budgetary level, ensuring the wellbeing of the exhibition and everyone involved. Another emotionally charged moment was dealing with the passing of one of the artists, Carla Marzán. Supporting the loss, navigating the mourning process, and completing her work with the energy of the TEA team, her loved ones, and her family was both heartbreaking and inspiring. Personally, we believe this is the project I’ve learned the most from and a truly beautiful circumstance unfolded: the entire team—artists, museum staff, and ourselves—ended up feeling like a family. This is a project we will never forget.

Carla Marzán, La escuché desde la otra montaña, 2024

On the audience and its significance

How has the public responded to the biennial’s public program? Which aspects of Canary Islands’ idiosyncrasy generated the most interest or debate?

The public program was pivotal—almost on the same level as the exhibition itself. On the one hand, we brought topics that hadn’t been addressed with such intensity in the islands to the forefront, shifting focus away from northern and central Europe and toward Eastern Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.

From a Canarian perspective, we went further, presenting identity-related questions from the forefront of critical thought on the islands. The Canary Islands are part of Spain and, politically and economically, part of Europe, but geographically, they belong to Africa, making them a great unknown within the Spanish state. There’s a remarkable artistic and intellectual strength here, particularly in decolonial and identity-driven thought, that struggles to be contextualized beyond the islands due to their geographic location and the fierce centralism of the art system.

The Biennial has been instrumental in putting this potential on the map both nationally and internationally, while also strengthening the local ecosystem by fostering confidence and providing resources.

Laura Mesa Lima, Dos moldes para un constructo, 2017

On culture in peripheral areas

Do you think events like this can help reverse cultural desertification in peripheral areas like Tenerife? How can projects like this revitalize the local cultural fabric?

We truly believe so, and in this sense, it is vital to organize major exhibitions that appeal to international audiences and receive media visibility. In this case, we both, along with the entire team, put all our efforts into creating a high-quality project, and that height could only be achieved from the periphery of the periphery. As we mentioned, the Canary Islands have a very high level of art and thought, and specifically, Tenerife is an island with numerous solid and constant cultural projects. However, breaking the barrier to the outside world is very difficult due to distance and territorial indifference. I, as a Canarian, know this well—it’s very challenging to break out, and at the same time, it’s also hard to stay in, even when venturing out and coming back. Projects like this help create connections and strength, and personally, we believe this energy should not fade. Cultural centralism is a scourge for contemporary thought that leads to homogenization, precariousness, disillusionment, and superficiality.

Anna Engelhart y Mark Cinkevich, Onset, 2023

On the impact of the biennial in the local context

The banana industry and colonial heritage are key themes in some of the works. How has this backdrop influenced the artistic proposals and the public’s reception?

More than the banana industry itself, the central themes of the proposals that addressed the local context focused on how history has been constructed, indigenous identity, mass tourism, modes of production, coloniality, and even the heteropatriarchal bias of folklore. There is a solid artistic, academic, and independent community that has been revisiting these issues for many years. The most important aspect has been to address these (often unknown outside the islands) topics in a leading way, also recalling the indivisible connection with nearby conflict zones such as the Sahara, while fostering dialogues with territories less related, like Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, Palestine, or Lebanon.

Regarding the public, we believe it was a success both in attendance and reception. Since both were physically present for most of the exhibition’s duration, we were fortunate to receive direct and very positive feedback.

Al-Akhawhat, +212, 2024, details

On the role of small biennials versus large exhibitions

What advantages do you think a smaller biennial like this one has over large international exhibitions? What spaces for dialogue or reflection can this format open that mass events don’t allow?

A freedom that would not be possible otherwise—the opportunity, in a small biennial, to create a large-scale project while embracing oddities both in content and in our curatorial profiles. Large biennials are often shaped by academic and market mandates that are almost impossible to avoid, whereas a smaller biennial allows much greater freedom, offering a higher degree of risk, where the real action in an exhibition happens, and the freedom to question oneself.

When we think of large biennials, we also think of mandates, but in this case, we’ve been able to talk about counter-mandates, heretic proclamations.

Dejan Kaludjerović, Dreams Station, 2024

To conclude, What has this biennial meant for both of you personally, in such a dystopian year like 2024? And what are your wishes for 2025?

It has been a major challenge professionally and personally, but one we would not hesitate to repeat. In times of dystopia, it’s important that resistance comes not only from form and content but from the ways of doing. For 2025, our main wish is to bring the biennial’s publication to fruition, which we are seeing as an even greater challenge than the biennial itself.

Maï Diallo, Corpus foramis, 2024, details

All images courtesy © TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes / María Laura Benavente Sovieri.

For more information, visit the website of the TEA Tenerife on the biennial.

(Front Image: Ariel Kuaray Ortega, Victor Leguy, Gabriel Bogossian, Caminhantes, 2022-2023)

María Muñoz-Martínez is a cultural worker and educator trained in Art History and Telecommunications Engineering, this hybridity is part of her nature. She has taught “Art History of the first half of the 20th century” at ESDI and currently teaches the subject “Art in the global context” in the Master of Cultural Management IL3 at the University of Barcelona. In addition, while living between Berlin and Barcelona, she is a regular contributor to different media, writing about art and culture and emphasising the confluence between art, society/politics and technology. She is passionate about the moving image, electronically generated music and digital media.

Portrait: Sebastian Busse

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)