Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

María Rosa Aránega (Almería, 1995) works at the intersection between image and memory, especially in regards to the Franco dictatorship, interrogating how history is inscribed and distorted in visual representations. Her research is an exercise in restitution and an investigation into the fractures of the official narrative where what has been silenced struggles to emerge.

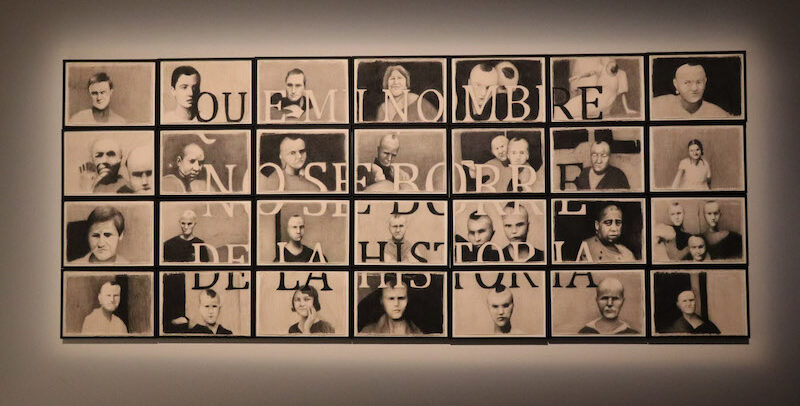

Que mi nombre no se borre de la Historia. Project El silencio I: la causa, 2022. Centro Conde Duque (Madrid)

Begoña Martínez Rosado: María Rosa, in your work, the memory of the dictatorship emerges as a personal history from a local perspective, though with collective resonance. How do you negotiate this intimate connection with official history, especially when family accounts conflict with it?

María Rosa Aránega: When I thought about conflict closest to our reality in Spain, it was clearly the dictatorship and the fascist coup d’état. My first resource was family memory, especially from my grandmother. This approach from home marked a turning point in my work, allowing me to address political violence from a legitimate perspective. By starting from the local level, the feeling of being an impostor disappeared, but it also involved negotiating between intimate silence and the abundance of official data. My grandmother’s stories contrasted with the archives and a paradox emerged, a wealth of decontextualized data versus her scant testimony. Everything changed when I discovered my great-grandfather in the Causa General, a man who fought in the war and died on April 3, 1939 by committing suicide. This discovery broke my grandmother’s silence and allowed me to construct a more complete account, going back and forth between sources. Ultimately, patterns of power tend to repeat themselves, and my work reflects on how history persists in these cycles.

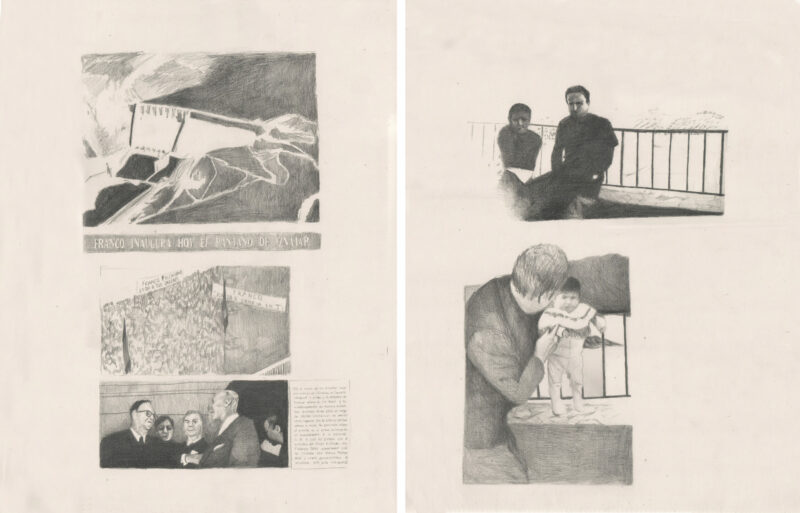

Hemeroteca sobre el pantano de Iznájar y Desde los miradores del pantano. María Molina’s Album. Project Un recuerdo de agua, 2023. Micla Espacio de Arte (Iznájar, Córdoba)

BMR: In your practise, institutional and family archives are not only sources of information but also hierarchical structures that shape memory. How do you address these tensions when the institutional archive contradicts intimate memory?

MRA: When I talk about horizontalizing archives, I mean connecting seemingly unrelated records and granting a family archive the same legitimacy as an institutional one. It’s not just a methodological decision but also a political one, as well, a questioning of official narratives by using intimate, everyday materials. I work with personally donated objects (clippings, postcards, invitations) that show how certain people saw themselves as historical agents, how they preserved certain moments with an awareness of their future value. While institutional archives aspire to a certain neutrality, family archives are emotional and fragmentary. This discontinuity is key, as families act as both authors and editors of their memories, in tension with official frameworks. My work seeks to legitimize these fragmented memories, making history more complex through every-day, emotional, and excluded material.

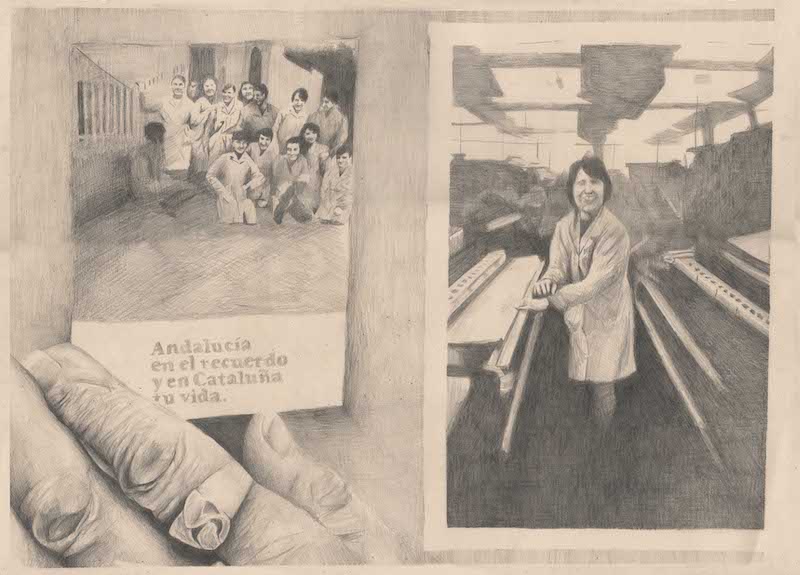

Ana Castaño’s Album. Project Amnèsia per abundància, 2024. A cobert (Moià)

BMR: In your body of work, one perceives a resistance to use the archive as a simple artistic resource. Would you say there’s a conscious decision not to force the production of work based on these histories?

MRA: Yes. My approach to family archives didn’t come from artistic intentions but rather from a commitment to the histories. The practice came later as a tool for exploration. The lack of urgency made the research more honest. I’m always guided by one question: How would I like another artist to treat my family’s memory? Working with these memories requires care. It’s dangerous to reduce victims to numbers or narrative devices. Anyone can address these issues, even without a victimized family member, as long as they do so ethically. Preserving families’ agency means not imposing interpretations but instead co-constructing them. By sharing memories, fissures in hegemonic narratives appear. Sometimes, creating a space for listening is meaningful and the family album, thus, becomes a crossroads between the private and the historical. An intimate image can reveal omissions in the official story, which is why, before I approach a family, I investigate the context to be able to read between the lines in the photos, as far as who appears, what is shown, and what is omitted. I’m also interested in the political and emotional role of family photography in repressive contexts. This has been a central focus of my work in Almería. I was greatly influenced by Jorge Moreno Andrés’s thesis, “Family Life through Photography in the Representation of Francoism,” which analyzes how these images mediate the legacy of disappearance and censorship.

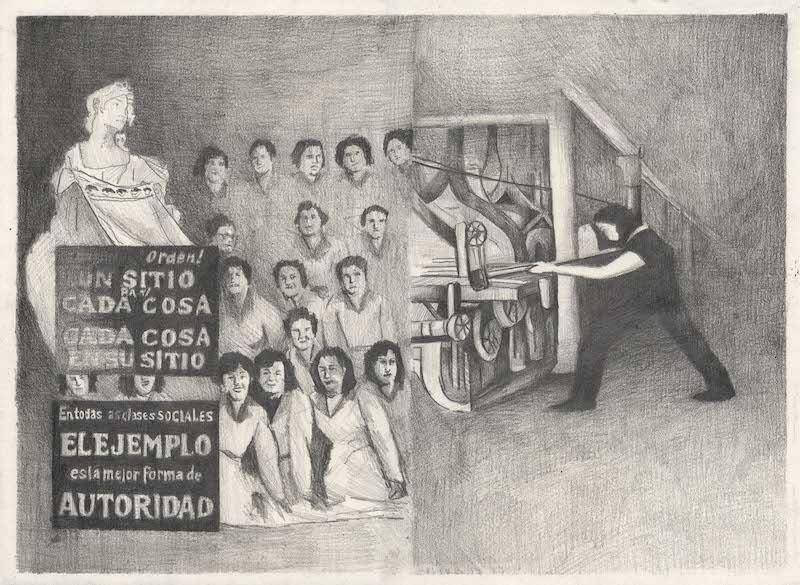

N/T (Textil work maps). Project Amnèsia per abundància, 2024. A cobert (Moià)

BMR: Your pieces with archives seems inseparable from an exploration of emotions. How do emotions operate in the construction of memory? How do emotional ties challenge official narratives?

MRA: This is an approach I also try to apply to exhibitions. I’m interested in the fact that, by placing family photographs in dialogue with institutional documents, everything becomes more powerful. Suddenly, people see themselves within a broader narrative, as if their archives were worth as much as those of a national library. It’s an important moment because it allows the private to be integrated into the collective narrative. Family narratives are fragmentary and emotional, and therein lies their power, for they challenge official narratives that are linear, complete, and supposedly neutral. This fragmentation allows us to approach history from the unexpected and from the intimate. I’m very interested in this friction because it opens up new ways of understanding history, as something alive and constantly under construction.

La distancia entre objeto y sujeto (nº 4, 5, 6 y 7), 2024. Centro Andaluz de la Fotografía (Almería)

BMR: Beyond documents, there are forms of violence that leave no material trace but whose effects persist. How do you address these forms of omitted violence? Can archives reveal them?

María Rosa Aránega: I’m interested in revealing the “silent” violence that leaves no physical trace but affects peoples’ lives, such as structural and economic violence, exile, and constant fear. Although official history ignores it, I combine personal testimonies with institutional records to show not only its existence but also its long-term effects, often hidden by discourses of progress. One example is that of the women who had their heads shaved during and after the war, a widespread practice throughout the country but rarely documented visually, which contributes to its invisibility as gender-based violence. The few images that exist are so powerful because they document systematic violence and allow for its extrapolation. This combination of exceptionality and everyday life makes them an especially valuable testimony.

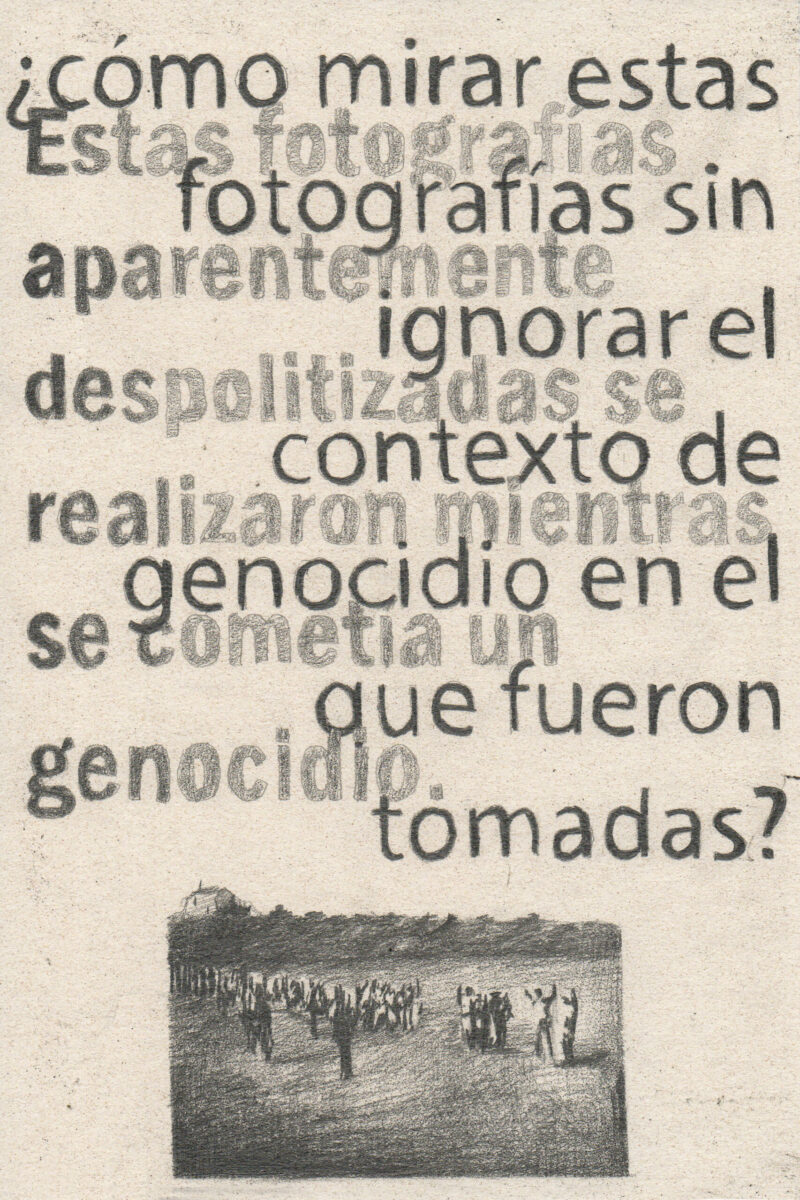

Cómo mirar estas fotografías… Exhibition La distancia entre objeto y sujeto, 2024. Centro Andaluz de la Fotografía (Almería)

(Front image: María Rosa Aránega drawing (detail), 2024. Photo: Eloy Ariza).

All the images © courtesy of the artist.

Begoña Martínez Rosado (Lima, 1995) is a researcher and cultural manager based in Spain since 2000. With a degree in Art History and a Masters in Latin American Studies from the University of Granada, she works from a transatlantic perspective that crosses archive, essay and visual practice. She is currently working on a doctoral thesis at the University of the Balearic Islands on coloniality and cultural identity in Mallorca, with the support of the Institut d’Estudis Baleàrics. She has worked in institutions such as La Madraza, the Cervantes Institute in Paris and independent spaces, and is currently part of the Exhibition Coordination team at the Centro Nacional de las Artes in Mexico City through the CULTUREX grant.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)