Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The generational question has been hanging over art for an unknown period of time. We do not agree on what a generation is, what this category is for and how much attention we should pay to it; even so, we do not cease to grope the word. As every year for the last 20 years, La Casa Encendida is hosting a new edition of Generaciones: eight artists under 35 years old called to summarize what young artists are doing.

There seems to be a certain consensus (at least in the scholarships and awards) that youth is what happens until you reach the mid-thirties. This is the stage of the emerging artist, the moment when things have to be demonstrated. Critics, gallery owners, curators and collectors search among the dossiers and scrutinise careers in the hope of finding the valuable fruits that the young creator is incubating in the age of great discoveries. There is a certain fascination with youth: with the new. The generational calls always establish an age up to. “Born until 1985”. Not between, which would be another completely valid option: examine, for example, what those who were born fifty years ago are doing. It seems that we would like to make a sieve: the one that has not stood out when it starts to comb gray hair, to the pylon. (Another day we will talk, if you want, about what happens to young promises after 35).

The suitability of the model raises so many doubts that the catalogue of this last edition includes an essay in which Professor Selina Blasco (who has been a member of many selection committees) examines in detail the profile of the artists who present themselves, of those selected, the interests that come to light in their proposals, their theoretical justifications, etc. In any case, the popularity of the format is undeniable. I myself (I will put the bandage before the wound) am busy these days selecting the artists who will be part of the next generational exhibition of the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo. It’s like that.

Generación 2020 is that of Javier Arbizu (Estella, 1984), Elisa Celda (Madrid, 1995), Oier Iruretagoiena (Guipúzcoa, 1988), Gala Knörr (Vitoria, 1984), Claudia Rebeca Lorenzo (Logroño, 1988), Miguel Marina (Madrid, 1989), Cristina Mejías (Cádiz, 1986) and Nora Silva (Madrid, 1988). Once again, it is curated by Ignacio Cabrero, who has faced the not insignificant challenge of mounting an exhibition with artists not selected by him and with works that have nothing to do with each other. The truth is that it has been resolved with a lot of solvency: one more strident room, another more sober one and two separate and dark rooms.

No Fall Games is a more or less aseptic space (a canvas defines a dark rectangle on the floor; above it, some wooden boxes -the kind you pack-, some fire extinguishers, a structure suspended from the ceiling with a lot of bolted video surveillance cameras, a screen that reproduces the fire in a loop, a work helmet) that is activated by some performers in translucent protective suits. Despite the ingenious title (a semantic game with those posters that forbid playing ball) we are faced with the umpteenth artistic revision of hyper-surveillance and hyper-exposure, the control mechanisms and the tensions between security and privacy. I will refrain from quoting a string of well-known examples and misreadings of Foucault. Although Nora Silva offers us an aesthetically solvent example, these actions always falter on the same point: they are empty. It is self-satisfying to proclaim that we are being watched and that we lend ourselves to it, but reflection – in order to be profitable in some way – must go beyond this simple enunciation. In this exhibition we will find many recurring themes from the history of art (nothing new under the sun), but this one does not go beyond the cliché.

The piece dialogues, in the same room, with Gala Knörr’s installation: a series of paintings and prints that reproduce the aesthetics and language of the millennials and the Internet. 2020 and we are still painting memes (and quoting, of course, Richard Dawkins). I don’t know if at some point the idea of switching to painting (the old) the digital images that riddle us (the new) was of any interest. The viewer can lie down on a huge cushion to watch a screen where the images of the protests and riots that provoked that “collective” and memetic reaction on the Internet follow one another while listening to the noise coming from some speakers. It is worth remembering Benjamin’s handy quote: the contemplation of self-destruction as an aesthetic enjoyment. And Benjamin wasn’t saying it for good.

I do not know the purpose of Silva and Knörr’s proposals, although I hope that they are purely rhetorical exercises. It would be too naive to expect that a work exhibited in an institution would have any effect on the “problem” they allude to. This first room, which we could read as an examination of the spirit of our times, is completed with the works of Claudia Rebeca Lorenzo. Txukela (which means “dog” in erromintxela, the language of the gypsies living in the Basque Country) is a series of sculptures (busts) framing three large portraits that have an air of primitivism and fauvism. These faces, of an allegedly crude construction (oil on sticks, unsophisticated welds, abundant adhesive tape), would like to generate tension between the atavistic and the contemporary. These pieces have the appearance of a tribal mask wrapped in many layers of tape.

Between the two theatres, Elisa Celda’s interesting film O arrais do mar will be screened, which has ways that are reminiscent of Albert Serra’s cinema. In 18 minutes, Celda explores the inexhaustible theme of the night, synchronizing the work of some fishermen (who use a traditional technique called xávega) with that of some men who seek each other out for sex under the cover of darkness. Let’s admire the fineness of the idea. The success of the film is, paraphrasing Alarcón, in opening wide the doors of the night. It is a darkness in which men put into practice primordial impulses (the search for sustenance, sex); where some use the light to illuminate themselves and others to find themselves and hide.

The next room welcomes the proposals of Oier Iruretagoiena, Miguel Marina and Javier Arbizu. In all three of them you can find an interest in memory, in the past and in tradition. In the murals of the series Paisaje sin mundo, Iruretagoiena adheres and encapsulates remnants of works by anonymous artists in a network of coloured and stapled plastics. The result is a noisy image (in which the myriad of staples that hold the different elements stand out) that is the result of the superimposition of layers: now a piece of a house, now a round with holes that allow us to look a little further, here some blue lines; a piece of paper, a stitching. This great image of decomposition and clutter can be the very image of memory (a set of entangled impressions) or of longing (another amalgam of assumptions). It is interesting to note the theme of the rescued images. They are country scenes, villages or landscapes. As we know, the landscape is essentially an invention of art, the result of the continuous resignification of nature over the centuries: from the fearsome forests to the garden (the domesticated forest) and the (ecological) reserves of the biosphere, through the bucolic fantasies of the Renaissance and the rural frenzy of Romanticism. Fractionated and reassembled, the construct becomes evident, more so when it is interspersed with such disruptive elements (semantically as far away) as plastic or staples.

In front, we find Javier Arbizu’s heads, feet, hands and the rest of the mutilations. They are pieces made of bismuth, a heavy, fragile metal that solidifies in a chromatic range that goes from silver to blue, gold or purple. Arbizu has devised two metal and glass displays that give his pieces a certain air of collection, each one on its own shelf (a structure, however, largely absorbs the presence of the pieces). Our cultural familiarity with the body parts is surprising: relics, reliquaries, archaeological finds, votive offerings, heraldic motifs, etc. Arbizu’s work reflects this tradition (and takes advantage of it), adding to it the rarity of the material he works with. Thus, we find a triple tension between the familiarity of the shapes of the body, the strangeness of seeing them separated and arranged for exhibition and, finally, the Martian nature of the material in which they are made. These impressions, however, are cushioned by the frequency with which we have seen these works by the Basque sculptor in recent years.

Miguel Marina is one of the most interesting and promising painters of the new batch. In Celada, however, he proposes an installation that looks like a stage set: a mosaic made of lentils, a feathered column with tiny strips of orange, a structure of panels assembled at right angles, long carved crossbeams and a modular hitch hanging from the ceiling are spread out on a platform. At one end a small square made of beeswax has been hung, which has a mineral look, similar to alabaster windows. Framed by these objects we see a brown paper in which orange and greyish motifs stand out discreetly.

Marina uses images from his memory in his recent work: the smudged impressions of a walk, a shape found in some church, that curious thing about that city he passed through. This, added to a growing process of formal refinement results in these unique pieces, somewhat clumsy in their making. His experiments with sculpture produce precarious objects, which the spectator (at least, this spectator) feels are accessories (minor, if you will) when faced with his pictorial work.

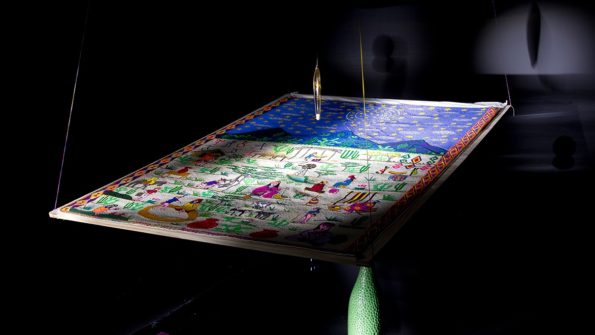

Finally, if one wants to see La máquina de macedonio, one will have to take one of the flashlights that Cristina Mejías has left on the shelf at the entrance. When entering the dark room, with the claustrophobic sensation of seeing only one point of light (white or ultraviolet), the visitor can walk through a tapestry that is suspended in the middle of the room, around which some pieces of glass have been placed to create glitter and reflections. The “experience” is achieved. The work is made by the Wayúu community of Yaguasiru, people who leave a record of their waking and sleeping stories in the tapestries made by their elders. Mejías ordered a piece that was manufactured by weavers from several generations and that has ended up in a room of La Casa Encendida. It is pertinent to ask ourselves at this point what is the point of delegating to a singular community the production of a piece of this nature, and then decontextualizing it (they weave, without a doubt, for other purposes) and resignifying it. I would not like to think that the customs that a people has perpetuated for centuries have ended up being the rhetorical justification of a dossier for a contest.

(Featured Image: Cristina Mejías. La máquina de macedonio, 2020 ©Manuel Blanco)

Joaquín Jesús Sánchez (Seville, 1990) is an art critic, writer and freelance curator. A graduate in Philosophy and holder of an MA in the History of Contemporary Art and Visual Culture, he contributes to prestigious publications, both in Spain and abroad, and in other lesser known sources. Besides researching compelling and complex subjects, he devotes much of his time to trying to memorise Borges’s oeuvre and is fascinated by gastronomic literature.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)