Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Pallay Pampa. Andean Crossroads is the current exhibition at ifa galerie’s space in Mitte, Berlin. Curated by art historian and professor Lizet Diaz, this project showcases the work of five Peruvian artists from different generations––Carolina Estrada, Juan Osorio, Kenyi Quispe, Emilio Santisteban and Daniela Zambrano Almidón––as well as an audiovisual essay based on research conducted by Adela Pino in collaboration with Isaac Ruiz and Alvaro Acosta. Although both the exhibition and the artworks began to take shape in 2019, the inauguration was postponed to 2021 due to the covid pandemic. The project is part of the larger long-term program Untie to tie – On Colonial Legacies and Contemporary Societies that ifa galerie has been working on since 2017. In broad terms, Untie to tie seeks to examine colonial legacies from the perspective of several related and contemporary issues such as migration, racism and the environment. In an effort to draw younger generations into the conversation, these topics are discussed in both online and in-person public programs, in collective works such as the recent Untie to tie: Colonial fragments in school contexts[1]Untie to tie. Colonial fragments in school contexts. Diallo Aicha, Niemann Annika, Shabafrouz Miriam (eds), ifa-Galerie Berlin, Bonn 2021. and in exhibitions such as this one, which features educational visits and activities in Spanish, English and German led by Peruvian artist Karen Michelsen Castañón.

The title, Pallay Pampa, comes from two Quechua terms related to the Andean back strap looms. The area that has already been woven is Pallay; it symbolizes what is said or has been said. The flat, vacant area is Pampa and it stands for what is yet to be said, for a future discourse. The title is thus a metaphor for the Andean conception of knowledge: something that in part is already established (handed down through ancient teachings) and in part remains open, amenable to change and reflection. As a whole, the exhibition seeks to approach the complexity of the Andean worldview and its experience of time. The pieces do not merely illustrate the topic but rather develop an active dialogue between these forms of knowledge and the premises and practices of the Western world. This is where we find the crossroads, in the contrast between two different experiences of time, two diverging ways of coexisting with the environment and caring for mother earth. Moreover, the notion of Andean identity is also put into question, showing that it is conformed and renewed through a network of exchanges in constant development.

The exhibition design was conceived by Studio Manuel Raeder and designer Rodolfo Samperio. Upon entering, in the middle of the first room we find Pedagogía textil andina, a four-channel video by Adela Pino, Isaac Ruiz and Alvaro Acosta. Projected on a horizontal wooden board, the videos introduces us to the Andean landscape and the everyday life of its inhabitants. Sitting at their doorstep among sacks of wool, some women weave while others shear sheep in a work process that is at once collective and pedagogic. Through their dialogue we learn that they used to make an income from the sale of their woven textiles until the pandemic struck in 2020, when the video was shot. The rest of the artworks are circularly distributed around this first one. To the right we have The Birth of Collaboration, a video installation by Carolina Estrada on how climate change has affected the rain periods in Quispillaccta, Ayacucho. While rainfall used to be evenly distributed over several months, it is now concentrated in just a handful of days. In order to preserve it, an ancient technique is used that consists in storing and collecting water from bofedales, wetlands located in the Andean heights that help purify and regulate the water flow, while also providing the earth with nutrients and maintaining the biodiversity of the local flora and fauna. The video shows how this technology is being used again today to make this natural resource sustainable in time.

AV installation by Adela Pino/Isaac Ruíz/ Álvaro Acosta

Left: Carolina Estrada installtion. Right: AV installation by Adela Pino/Isaac Ruíz/ Álvaro Acosta

Next, in a separate space, the video Suma Quamaña en la ciudad, by Daniela Zambrano Almidón, is projected from the roof onto a large, low table. The table’s perimeter is shaped like Lake Titicaca while the surrounding space is criss-crossed with a thread of alpaca. The video shows a dialog between the artist and the yatiri (sage) Apu Qullana Mallku, who expounds on the knowledge and practices of the Andean worldview. The spectator may miss out on the fact that Lake Titicaca is part of an underground water system that culminates in the sea. It is also a sacred place due to its location between two wak´as –Pachaqamac and Titiqaqa– which originally made up the centre of the Tawantinsuyu. Less evident still, the circuit of threads that radiates form the video perimeter may allude to the various exchanges and interactions that the Andean community maintains with that complex organism that is the Pacha. These exchanges are performed through the sarnaqami, the walk, a notion which views production not only as an earthly activity but also a sacred one, addressed to the gods.

Daniela Zambrano Almidón

One of the topics discussed by the yatiri is the notion of time. In the Andean worldview, past and future are simultaneously lived through the present itself. Time is not linear like in the Western tradition––it is cyclical. We thus arrive at two pieces by Kenyi Quispe: Contigo, a sheet of paper with the lyrics to a part of the song “Contigo Perú”, and ¿Qué viene después del futuro?, which consists of a text and an engraved stone with the words “Life implies death”. In the next room, the notion of time is further developed by the works of Juan Osorio. His installation PACHA – Dynamische Parität (Dynamic Parity) consists of plexiglass sheets that hang from the roof in the shape of an accordion. On them we can read a poem by Peruvian poet José María Arguedas and some Quechuan and Aymara concepts about the Pacha. To one side, on the floor, a TV screen projects Tiempo/Time/Zeit/Pacha, a video based on the film “Runan Caycu” (1973), by Nora de Izcue, about the life of Saturnino Huilca, a peasant form Cusco. The video has been intervened by the artist so that the events develop backwards instead of forwards. Moreover, the text of the installation breaks away from the traditional left-to-right script, prompting the spectator to find potential meanings between the words.

Front: written piece by Kenyi Quispe

Juan Osorio

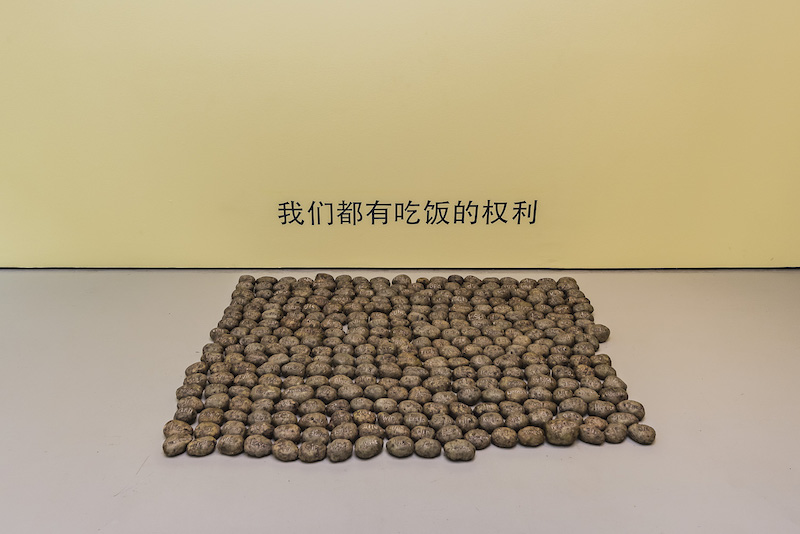

The piece by Emilio Santisteban, 我们都有吃饭的权利 (We all have a right to eat), consists of 324 Adretta potatoes carefully laid out on the floor and telling a story. A word is carved into each potato so that together they form a narration about interconnected beings written by Santos Vilca Cayo, an elder and farmer from the Andean Plateau. As time passes, the potatoes sprout and the words begin to warp until they finally disappear. The text is a call to all living beings on Earth––grains, vegetables, animals, plants, flowers and even diseases, since they are also a part of the ecosystem we live in. Andeans consider their crops as living beings with which they can lovingly converse, exchanging each other’s gifts in respectful reciprocity. The third and last piece by Kenyi Quispe can be viewed both at the end and the beginning of the exhibition. Art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson says that work with fiber can turn into a form of writing. Consequently, on the upper margins of room walls we can read a poem by Quispe himself, inspired by a trip he made to Lake Titicaca in 2019 with the curator and some the artists featured here.

Emilio Santisteban

The exhibition leads us to reflect on the relevance of ancient Andean knowledge in communal forms of self-management, on community resilience and on the idea of a multiple temporal dimension which breaks away from the goals of productivity and specialization, at the base of the current Western form of knowledge. As a foreigner in this city that now comments on a culture which is not her own, I wonder how this knowledge and these experiences can translate onto a city like Berlin, which has recently inaugurated the controversial Humboldt Forum. The artworks featured in Pallay Pampa give insight into the complexity of the Andean culture while at the same time questioning our own configuration of the world, the formation we receive outside institutional spaces, the way we exist in our natural, human and spiritual environment. On a personal note –and following the words of Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui[2]Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera, Un mundo ch´ ixi es posible. Ensayos desde un presente en crisis. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón, 2018.– they help me to continue to act from that knowledge which resides in our heart, kidneys and lungs and which the Aymara tongue sums in the word amuyt´aña. Let us use this moment of crisis and transition to turn our attention towards things fragile and small, things that can herald a new praxis, a new consciousness with which to imagine a new future.

Exhibition view

Exhibition view

All images by Victoria Tomaschko.

(Front image: Carolina Estrada)

Pallay Pampa. Encrucijadas andinas

16.09.21 – 02.01.22

ifa Galerie, Berlín

| ↑1 | Untie to tie. Colonial fragments in school contexts. Diallo Aicha, Niemann Annika, Shabafrouz Miriam (eds), ifa-Galerie Berlin, Bonn 2021. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera, Un mundo ch´ ixi es posible. Ensayos desde un presente en crisis. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón, 2018. |

Renata Cervetto has a degree in art history (Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2011) and graduated from the curatorial program at the Appel arts centre in Amsterdam (2013-2014). In 2014 she obtained the first Curatorial Fellowship granted by the Ammodo Foundation (NL), for which she researched artistic and curatorial practices in dialogue with pedagogy. This practical and theoretical work has been compiled in the book “The Fellow Reader #1. On Boycotts, Censorship and Educational Practices” (from Appel art centre, 2014). Between 2015 and 2018 she was Coordinator of the Education area of MALBA (Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires). In 2016, she co-edited the publication “Shake before you use. Educational, social and artistic displacements in Latin America” together with Miguel A. López (TEOR/éTica and MALBA. 2017). Between 2019 and 2020, she was curator of the 11th Berlin Biennale, “The cracks begin within”, together with Agustín Pérez Rubio, María Berríos and Lisette Lagnado.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)