Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

We are going to take a look at Manila’s contemporary art scene through two exhibits: “SaLang #5: Liberties were Taken” at Project Space Pilipinas[1]”SaLang #5: Liberties were taken” is an iteration of an earlier exhibit “Liberties were Taken” which took place at the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston, Texas from May 31-August 18, … Continue reading, an artist-owned gallery in the town of Lucban, and “Shrine for the Battle Dance” at the Drawing Room Manila in metropolitan Makati.

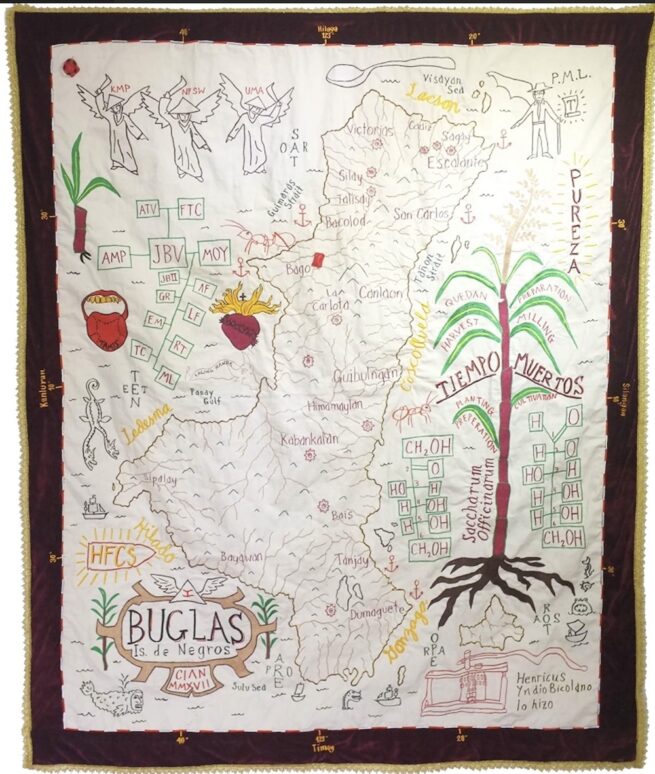

It was Cian Dayrit’s (b. 1989) tapestry, “Mapa de la Isla de Buglas” (2017), that first drew me in. Familiar words in Spanish and English take their place beside indigenous place names and Tagalog[2]Tagalog is the official national language in the Philippines, where between 120-195 languages are spoken. acronyms in a map representing the central Philippine island of Negros. Chemistry, cartography, and linguistics are all at play here, in dialogue with environmental, historical and political events. A fabric frame of gilt and velvet monumentalizes this kaleidoscopic coexistence. The more you look,the more the meaning of these words and symbols on the map shift and take on other meanings, in a process of counter-cartography that ultimately asks us to question our place in this conflicted universe.

”Mapa de la Isla de Buglas,” 2017. Courtesy of notanatlas.org

The tapestry is anchored by a sugarcane plant, here identified by its genus and species “saccharum officinarum.” “TIEMPO MUERTO” sits across two branches, signifying the time between sugarcane harvest and planting, when there is no work and usually, therefore, no food for field workers.

On the top left are what seem like avenging angels in robes, curved “espading” knives raised as if ready to strike. Personifying various worker and peasant organizations, they are identified by the acronyms that accompany them. Numbering in the hundreds of thousands, sugar field workers have been victims of state-sponsored oppression and violence.

The artist names the the map “Buglas”, the original indigenous (Hiligaynon) name for this island, which the Spanish had re-named “Negros” in the 16th century upon their arrival. In this renaming, Dayrit rejects the colonial and imperialist identity imposed on the island as an agricultural monoculture producing sugar as a commodity. The Roman numerals under the artist’s name “CIAN” recall the fall of an empire. The map is signed at the right in Spanish “Henricus, Yndio” by Henry Caceres, who collaborates with Dayrit in this polyphonic narrative through embroidery.

***

“The Philippines, 7,641 islands with a population of about one hundred million. Abundant in minerals and natural resources. Producer of tropical cash crops, and raw material for export to industrialized nations. Breeder of generations of disenfranchised cheap labor and a market for excess finished goods … home to foreign multinationals partaking in the bounty of tropical ingenuity and subordination via neoliberal policy … “ – Cian Dayrit/Erika Mei Chua

***

A four-hour drive south, away from the unrelenting traffic of Manila, takes you to Project Space Pilipinas (PSP) in the town of Lucban[3]The town of Lucban was featured in Mark Salvatus’ installation for the Philippine Pavillion at the 2024 Venice Biennale. and Dayrit’s exhibit “SaLang[4]SaLang comes from the words “[I]sa” or “one,” and “Lang” or “only” and began as a title to a single-work exhibition series at PSP. “Na-salang” also means to be put or placed, … Continue reading #5: Liberties were Taken.” You may find PSP unexpectedly, behind a gift shop which has sometimes served as an art space extension featuring video installations and other art objects.

Run by curator and artist Leslie De Chavez, PSP brings contemporary art to audiences outside the metropolis. Access is usually only available in Manila, though there are some notable exceptions to this such as Project Orange in Bacolod on Negros Island where De Chavez recently curated a show. According to him, PSP prioritizes “our exhibiting artist(s) and their art in relation to our audience.”

In order to further community dialogue with the ideas in Dayrit’s work, De Chavez invited members of the public to engage with the art on a variety of levels through various organized events, well aware of the distinction between an encounter with art and a deeper engagement with its ideas, some of which are weighty. Wall texts are kept short and simple at PSP with a bit of poetry thrown in: Kumbaga, gusto namin na parang nililigawan ka nung ideas or texts habang binabasa mo sya. “It’s as if we want the texts and ideas to make you fall in love with them as you read them.”

***

To enter the main exhibit space at Project Space Pilipinas, you first pass through narrow entrance hall. Then, you find a well-lit rectangular white space, which leads to two smaller rooms beyond.

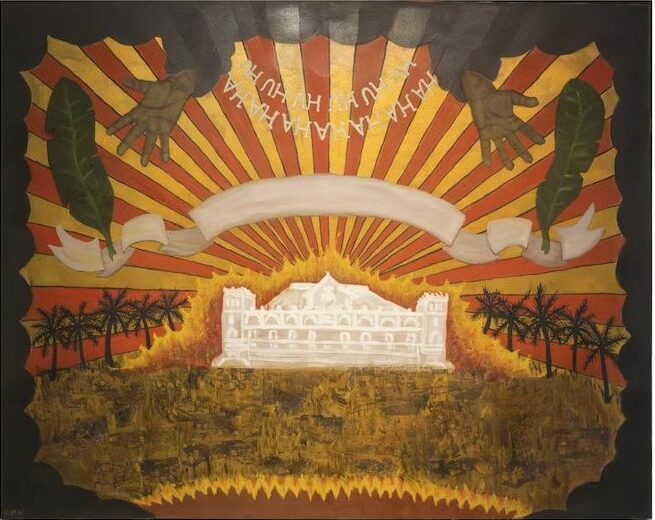

“Monument of No Meaning,” 2018. Courtesy of Project Space Pilipinas

“Situated along the Pasig River in the Manila district of San Miguel, the Malacañang Palace is the official residence and principal workplace of the President of the Philippines. Since 1863, the palace has been occupied by eighteen Spanish governors-generals, fourteen American military and civil governors, and later the presidents of the republic.” – Cian Dayrit/Erika Mei Chua.

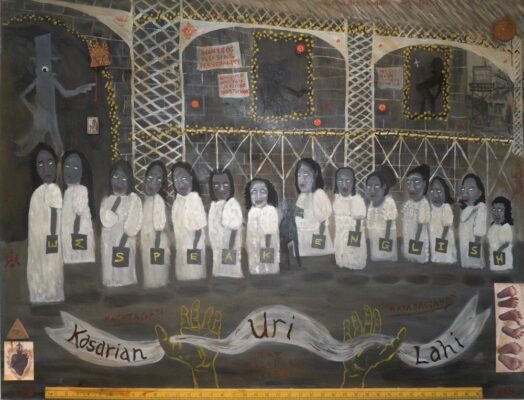

“We Speak English”, oil on canvas, 2018. Courtesy of Project Space Pilipinas

“Dayrit’s extensive practice examines the vestiges of nation-building from the colonial systems imposed upon Philippine society. Education played a large role in the attempt by the United States government to instill American values in the population, promote foreign interests, and ‘modernize’ the Philippines during the U.S. occupation from 1898 to 1946. The Thomasites were a group of six hundred teachers from the United States who arrived in the newly occupied territory of the Philippines in 1901. They established a new public school system to teach basic education and train Filipino teachers with English as the medium of instruction.” -Cian Dayrit /Erika Mei Chua.

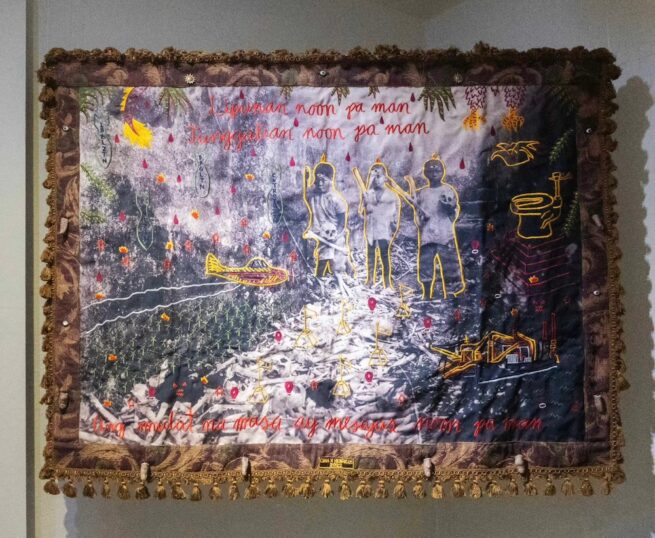

“Masa ang Mesiyas Noon Pa Man,” 2022. The title of this work, embroidered in red at the bottom, translates into “the mases (masa) are the Chosen Ones (mesiyas), and have always been.” About 36% percent of Filipinos are peasants reliant on agricultural work.

***

If a visit to Lucban is not possible, PSP’s thorough social media is particularly thoughtful. You wouldn’t guess that it is a volunteer, not-for-profit space funded by De Chavez’ artistic practice. But you can also see Dayrit’s work at “Shrine for the Battle Dance” at The Drawing Room Manila in Makati, long since the financial and entertainment center of the country. “Shrine for the Battle Dance,” which features Dayrit’s more recent 2024 works, occupies the central space. Other rooms feature various artists in both solo and group exhibitions.

“Shrine for the Battle Dance” shines a spotlight on the plight of some Filipinos as the extraction of the country’s natural and human resources continues unabated. An unrelenting mall-ification at the expense of public spaces offers believers a veneer of progress, “[a]ll welcomed and legitimized by an unbroken line of regimes pimping out our nation to the global ruling class” says curator Antares Gomes Bartolome, words that can be used to describe the common plight faced by members of the “global south.”

“Working archive of history from the ground 1-10,” 2024

“Working archive of history from the ground 1-10.” On the top row, second to the left, the work reads Sabi ni hepe magkaka mol daw sa komunidad natin pero bawal daw tayo d un. This translates to: “The boss says we will have a mall in our community. But, we are not allowed there.”

In the center bottom row is a map of one worker’s commute, which shows a one- hour bike ride that must be undertaken before they can even access public transport. Sagad sa hirap, kapos sa sarap. “Mired in hardship, short on delights.”[5]Translated by Anna-Lea Mejía.

“Shrine of the battle dance 1 & 2,” 2024. Photo: Maria Victoria Yujuico

| ↑1 | ”SaLang #5: Liberties were taken” is an iteration of an earlier exhibit “Liberties were Taken” which took place at the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston, Texas from May 31-August 18, 2024, curated by Erika Mei Chua. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Tagalog is the official national language in the Philippines, where between 120-195 languages are spoken. |

| ↑3 | The town of Lucban was featured in Mark Salvatus’ installation for the Philippine Pavillion at the 2024 Venice Biennale. |

| ↑4 | SaLang comes from the words “[I]sa” or “one,” and “Lang” or “only” and began as a title to a single-work exhibition series at PSP. “Na-salang” also means to be put or placed, while “Salang” means to take one’s turn or to be in the spotlight. In the old vernacular, it may also mean “to touch.” |

| ↑5 | Translated by Anna-Lea Mejía. |

Maria Victoria Yujuico writes about the intersections between art, literature and modern life. She holds a masters in Spanish and Latin American literature and is a student of contemporary art at IL3-Universidad de Barcelona. She lives in California, between the Monterey Bay and the San Francisco Bay Area.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)