Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

For Better Porter and Andrea Galaxina.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957-1996), an American of Cuban origin, is one of contemporary arts most lyrical artists, both aesthetically and ethically, as evidenced by his installations composed of everyday materials, such as watches, stacks of photocopies, posters, photographs of everyday scenes on billboards, or candies. As the art historian and fanzine publisher Andrea Galaxina (2022: 103) explains, Gonzalez-Torres’ work uses the static structures of minimalism but breaks conceptually with this movement by going beyond its neutrality, imbuing his work with references to his own personal history. In this way, the work of Gonzalez-Torres becomes a political act. Gonzalez-Torres, who was living with HIV/AIDS, used his work as a way to speak out about the disease, from his existence as a gay, immigrant and Latinx man, without casting himself as a victim. Another one of the key theoretical and aesthetic elements of Gonzalez-Torres’ work is his relational aesthetics.

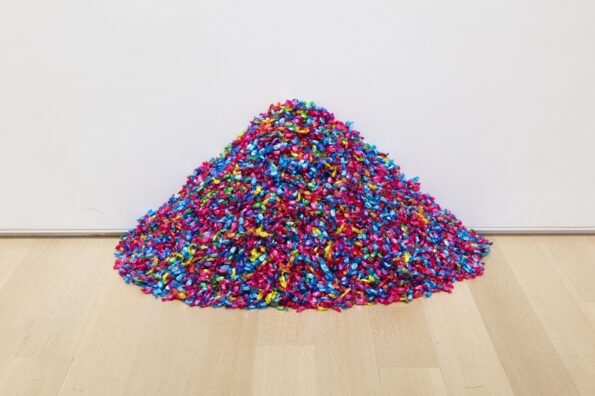

Among other things, Gonzalez-Torres used candies to create individual or paired portraits. Among the paired portraits, it is worth highlighting Untitled (Loverboy) from 1991, a portrait of the artist and his partner, Ross Laycock (1959-1991), in which the quantity of candies corresponds to the weight of both of them together, approximately 355 pounds. Among the individual portraits, one of his most popular and well-known installations, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), also from 1991, is an allegorical portrait of his partner, Ross Laycock, who died on January 24 of that year due to an HIV/AIDS-related illness.

The installation consists of 174 pounds of candies, Laycock’s weight when diagnosed with HIV, installed on the floor of the exhibition space. This mound of sweets undergoes constant change and renewal as members of the public pick up candies and take them with them, to save or to eat, thus transforming the initial weight of the work. The institution hosting the exhibit must constantly renew the work, which thus only gains its true meaning through the intervention of other people beyond the artist.

The reduction of the mountain of candies offers, therefore, a multiple metaphor, open to as many interpretations as one might want to give it. On first reading, and taking into account the moment in which this work was created and exhibited for the first time (1991), it can be taken as a literal interpretation, both biologically and socially, of the effects of AIDS. Visitors subvert the passive observation process that is usually expected of them in this type of space to become agents of the work through their intervention. In turn, this mediation supposes a moment of bonding that, breaking with the initial stigma of the disease, reaches “communicative extremes that had only been achieved in the Catholic rite of communion” (González Iglesias, 2001) by converting the exhibition material into a body of his body, that is, the candies that compose the portrait.

In addition, this work offers a temporality that breaks with the productive project of capitalist society. Being built from the threat caused by AIDS, and going beyond the total annihilation of the time in which it is created, it questions and reconsiders the organization of time in capitalist society. Abandoning the paradigmatic temporal markers of the heteronormative life experience, Gonzalez-Torres presents new ways of being in the present and in the future. In his commitment to the ephemeral, the work of Gonzalez-Torres not only adjusts “to the human scale in time and space” (González Iglesias 2001), but with this ephemerality he provides the key to queer affirmation, both that of his own identity and of others in the present

According to José Esteban Muñoz (2019: 65), since evidence of queer practices and identities has historically been used to penalize and discipline desire, connections and acts of this type of subject, there is rarely ‘reliable evidence,’ at least in the traditional sense of the term, to historically confirm the existence (past, present and future) of these people. Therefore, according to Muñoz, the key to tracking the ways in which queer identity is demonstrated and interpreted is through its union with the concept of ‘ephemeral memories:’ traces, remains, things that remain in the air. Exactly like Gonzalez-Torres’ portraits.

Nonetheless, as Muñoz himself observes, memory is an element that is constructed and, therefore, it is always political (2019: 35). Gonzalez-Torres understood aesthetics, and his work, in these terms. Yet, in recent years, the omission of crucial information about Gonzalez-Torres’ queer identity, as well as the AIDS epidemic in which it was created, has been surprisingly common.

In 2016, the joint exhibition carried out by Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York, Massimo De Carlo in Milan and Hauser & Wirth in London, omitted information referring to the life of Gonzalez-Torres in the explanatory materials of these three venues. In 2017, the retrospective dedicated to the work of Gonzalez-Torres at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York omitted from its press release any mention of HIV/AIDS, Gonzalez-Torres’ status as an immigrant and a person with AIDS, his openly homosexual identity, his relationship with Ross Laycock, as well as the cause of their deaths from complications related to the AIDS virus. Instead, the focus of the text was diverted towards the formalist tendencies based on minimalism in Gonzalez-Torres’ work, as well as the many interpretations of his work.

In that same year of 2017, the David Zwirner Gallery together with the Andrea Rosen Gallery took charge of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation. In this way, the current custodians of his legacy erased one of his work’s most important dimensions. According to them, they did so in favor of the previously mentioned multiplicity of interpretations of the work. However, this should not be a reason to argue for the exclusion of decisive information in order to understand the work of Gonzalez-Torres, even more so when the personal, political and social context in which it was created has such important weight. These art world institutions become accomplices in the erasure of lives with AIDS, a cancel culture that is not talked about but which has direct consequences on recent history (not only of art) and its protagonists.

In the case of Gonzalez-Torres, deleting his biography means leaving his works empty, visually captivating but conceptually incomprehensible, stripped of the wonder and his strength to tell the truth about himself, which was the truth of the world of those terrible years in which art became a means for fighting against the abandonment and inefficiency of government institutions and the manipulation of the mass media, with its victimizing narrative of people with HIV/AIDS. The work of Gonzalez-Torres is still a living testimony of this, that is, as long as it is not deliberately censored.

The most recent case of this type of censorship, related precisely to the portrait of Ross, has, at least, a happy ending. At the end of September 2022, the user @willscullin announced that he would not renew his membership to The Art Institute of Chicago, one of the largest and most important museums in the world, after seeing that all references to the relationship between Gonzalez-Torres and Laycock, as well as any mention of HIV/AIDS, had been removed from the Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) text. The museum’s description stated that the ideal weight of the installation “corresponds to the average body weight of an adult male.” In this new text, the work of Gonzalez-Torres is characterized as one with “a sense of silent elegy,” without explaining the reasons for the lyrical sadness that is attributed to him, and focusing only on praising his aesthetics.

In this last case, the mobilization in social networks (which reached the Wikipedia page of the installation) made the Art Institute of Chicago include in the informative text the sexual-affective relationship of Gonzalez-Torres and Laycock, Laycock’s HIV-positive condition, his death from AIDS-related complications, as well as Gonzalez-Torres’ death for similar reasons five years later. After the scandal, the response on social networks was quite fast, and at the end of that autumn the new corrected information was already available, accompanying the work physically in the museum as well as on its website.

Beyond the lyricism that frames this portrait and the work of Gonzalez-Torres as a whole, the importance of contextualizing it is based on the fact that the AIDS epidemic is not a thing of the past and is not yet over. As per the famous slogan of the activist organization ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power): SILENCE = DEATH. Although current mortality has decreased significantly, as Andrea Galaxina recalls, “survival is closely linked to the possibility of accessing the necessary medical resources. Anyone can get HIV, but surviving it is still a privilege” (2022: 47).

References

GALAXINA, Andrea (2022). Nadie miraba hacia aquí. Un ensayo sobre arte y VIH/Sida, Madrid, el primer grito, 2022.

GONZÁLEZ IGLESIAS, Juan Antonio (2001). “Lo humilde y lo sublime: Apología de los caramelos”, ‘De cerca’, ABC Cultural, 10 de febrero 2001, p. 27.

HALBERSTAM, Jack J. (2005). In a Queer Time and Place. Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives, Nueva York, New York University Press, 2005.

MUÑOZ, José Esteban. (2019). Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. 10th Anniversary Edition. Nueva York: New York University Press.

[Thanks to Juan de Salas and Beatriz Ortega Botas & Leticia Ybarra from @juf.project to have lead this article to A*DESK]

[Imagen destacada: Félix González-Torres, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991. Candies in various colored wrappers, endless supply. Dimensions vary with installation; ideal weight 175 lbs. Gift of Donna and Howard Stone. Art Institute of Chicago Collection. ©The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation]

Marta Martín Díaz has a degree in Classical Philology from the University of Salamanca and a Master’s Degree in Reception of the Classical World from University College London. She is currently working on a doctoral thesis on the political dimension of Lucretius’s De rerum natura and its receptions in queer thinkers and artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. Of these receptions she is particularly interested in her link to the HIV/AIDS crisis. She is part of the Queer and the Classical (QATC) collective: https://queerandtheclassical.org/

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)