Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

He was born in 1959 weighing eight pounds —more than three and a half kilos. This is the first line of a seven-line biography written by Jürgen Baldiga in 1992, a year before he ended his life after recognizing the inevitable and near end of having been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in 1984. The emphasis on weight is not accidental; the body of HIV/AIDS is a body that disappears doubly, on the one hand, because of political and health neglect and, on the other, because of the consequences of the disease itself —Lets remember Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), the 1991 portrait of Ross Layock by Félix González-Torres: a pile of candies representing the weight of his healthy body that gradually disappeared and diminished as the public picked the candle up. In addition to the double disappearance, the iconography of the HIV/AIDS body in the 1980s and 1990s was constructed by the media “as the image of a martyred man, lying down, marked all over by the disease[1]Lebovici, Élisabeth, Sida, Arcadia Editorial, MACBA, Barcelona, 2020, p. 26..” Lets remember, too, the People with AIDS series by Nicholas Nixon, who went to the residences as a volunteer, or the photograph Therese Frare took of David Kirby that ended up becoming a Benetton campaign— an imaginary that determined “to a large extent the perception that most people have of all aspects of the epidemic, from health promotion to issues of discrimination, prejudice, care, treatment and service provision[2]Watney, Simon, “Short-term Companions: AIDS as Popular Entertainment”, en Klusacek, Allan y Morrrison, Ken (eds.), A Leap in the Dark: AIDS, Art and Contemporary Cultures, Véhicule Press, … Continue reading.”

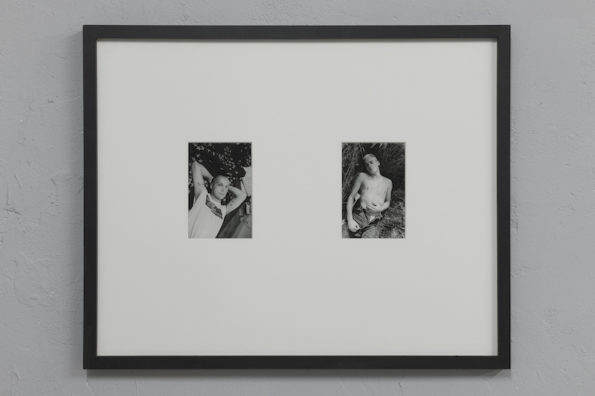

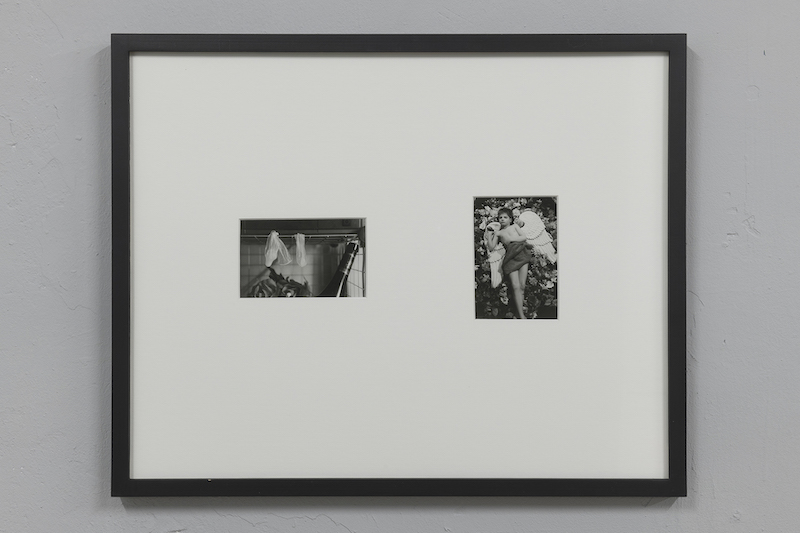

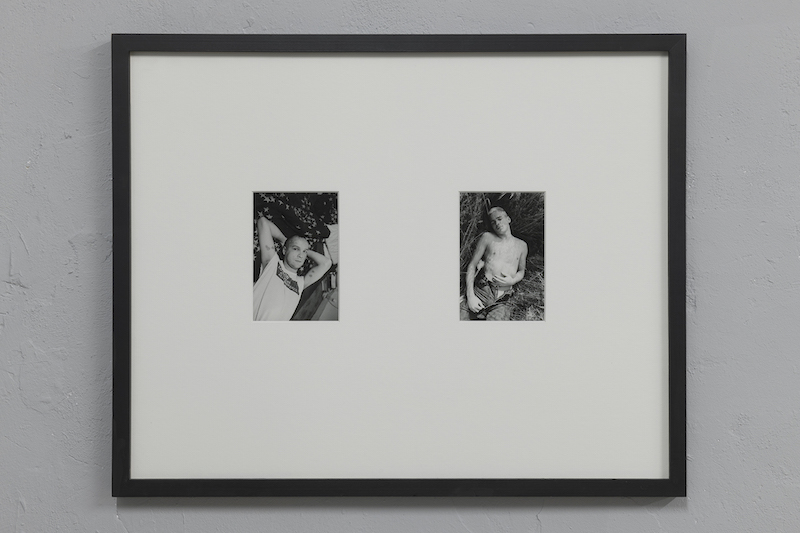

Far from this gaze towards other that turns the subject into an isolated victim is the photographic diary-work of Jürgen Baldiga that could be seen until November 27th in the exhibition Hover in Cordova (Carrer de l’Encuny 24, Barcelona), a testimony that contradicts the idea of a body of HIV / AIDS that disappears, after taking of responsibility for self-representation found both, in Baldiga and in other artists who were diagnosed with the virus, they have managed to build a political memory, and also a poetic and sensual one, to which we continue to turn to today. These are twenty photographs composed in diptychs that bear witness to an intimate and everyday look in which friends, lovers, strangers and also the Berlin drag and lgtbq community are documented. As a yearning for permanence and a will to build his own narrative, it is worth noting that Baldiga’s photographic career begins a year after being diagnosed and ends with his death in 1993.

A man and a boy both winged opened and closed the narrative proposed by the selection of photographs —a small part of an archive of thousands of photos currently kept at the Schwules Museum in Berlin—, a narrative accentuated by the format chosen by Baldiga himself, who was the one who enlarged the photographs and arranged them in diptychs pointing to a possible reading of them through the relationship. The images show moments of intimacy, desire, pain and death together with some images —like that of a tank with two soldiers next to another one in which some friends or co-workers hugging in a sort of kitchen— that allow us to guess the specific socio-political context in which these images were taken: that of the German reunification.

Historian and journalist Élisabeth Lebovici speaks about the intimate dimension of the archives linked to AIDS, writing that “the notion of intimacy is installed in the cultural space. […] a scenography of the intimate: as if it were also necessary to break with the supposed neutrality of the place of representation, and to draw a new configuration in which the limits between outside and inside, between the private sphere and public space, become even more porous, like those that seropositivity and the epidemic have produced[3]Lebovici, Élisabeth, op. cit., p. 34”. Documenting the intimate space became, then, necessary, since the media and society were denying it to the homosexual community, considering that intimacy was the very symbol of infection.

Of course, and as Lebovici also points out, we are not talking about an isolated but a collective intimacy, in which the boundaries between the private and the public are blurred. Jürgen Baldiga was, in this sense, a sort of chronicler of the lgtbq community in Berlin during the years in which he took photographs, which he not only documented but also participated in very actively. With the rise of AIDS in the 1980s in Germany, the lgbtbq movement began to integrate into political and social structures and activist groups multiplied. The spread of the virus also led to the creation of local and regional associations for help and support, such as AIDS-Hilfe or the ACT UP group in Germany, in whose actions Baldiga took part at some point. After all, as activist Sejo Carrascosa points out, “to talk about AIDS is to talk about its history, about the fight against the pandemic, about the injustice embodied in the most vulnerable bodies, about gender, social classes, racism, homophobia and transphobia. To talk about how the differences and hierarchies between bodies have been constructed and to what interests they responded and continue to respond[4]Carrascosa, Sergio, “Nadie hablará del sida cuando estemos muertas” en Vila, Fefa y Sáez del Álamo, Javier Ed. El libro del buen amor. Sexualidades raras y políticas extrañas, Ayuntamiento … Continue reading.” Echoes of this list of urgencies, of urgent and affectionate glances to the margins, can already be perceived in the twenty photographs by Jürgen Baldiga that were on view at Cordova.

Baldiga’s set of photographs speak to us of a sensuality that is also possible for the infected body, for the dissident body. A message with a very powerful political force that joins, fortunately, a choral voice of exhibitions or references to this collective memory around AIDS and sexuality in Barcelona, such as the recent exhibition El azar de la restitución. Pepe Espaliú in Barcelona (and Alberto Cardín) at Nogueras Blanchard curated by Joaquín García Martín; La pisada del Ñandú (o cómo transformamos los silencios) at La Virreina. Centre de la Imatge curated by Río Paraná (Mag De Santo & Duen Sacchi); Félix González Torres. The Politics of Relation at MACBA —despite the questionable reading that the museum proposed on many of the works; even El sentido de la escultura curated by David Bestué, with the collaboration of Martina Millà at the Fundació Miró, in whose tour you find the powerful image from 1991 of the doctor Fernando Aiuti kissing the HIV positive Rosario Iardino, to prove that HIV was not transmitted by oral contact; or the research work of the re team that led to Anarchivo Sida.

A whole set of exhibitions that together with Hover in Cordova, with photographs by Jürgen Baldiga, manage to recover and circulate archival materials that sent us back the story of the history of the lgtbq community. And insisting on the need for a sensual, affective and political memory, I end with Ann Cvetkovich: “[…] the affective power of a useful archive, especially an archive of sexuality and gay and lesbian life, which must preserve and produce not only knowledge but feelings. Lesbian and gay history needs a radical archive of emotions, in order to document intimacy, sexuality, love, and activism —all areas of experience that are difficult to document through a traditional archive. In addition, gay and lesbian archives address the traumatic loss of history that has accompanied sexual life and the formation of public policy on sex, and reaffirm the power of memory and affect to compensate for institutional neglect[5]Cvetkovich, Ann, Un archivo de sentimientos. Trauma, sexualidad y culturas públicas lesbianas, edicions bellaterra, Barcelona, 2018, p. 320..”

| ↑1 | Lebovici, Élisabeth, Sida, Arcadia Editorial, MACBA, Barcelona, 2020, p. 26. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Watney, Simon, “Short-term Companions: AIDS as Popular Entertainment”, en Klusacek, Allan y Morrrison, Ken (eds.), A Leap in the Dark: AIDS, Art and Contemporary Cultures, Véhicule Press, Montreal, 1992, p. 152. |

| ↑3 | Lebovici, Élisabeth, op. cit., p. 34 |

| ↑4 | Carrascosa, Sergio, “Nadie hablará del sida cuando estemos muertas” en Vila, Fefa y Sáez del Álamo, Javier Ed. El libro del buen amor. Sexualidades raras y políticas extrañas, Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 2019, p. 61. |

| ↑5 | Cvetkovich, Ann, Un archivo de sentimientos. Trauma, sexualidad y culturas públicas lesbianas, edicions bellaterra, Barcelona, 2018, p. 320. |

Marta Sesé researches and writes abour contemporary art. She lives in Madrid and works in arts publishing. She also co-manages the project Higo Mental: www.higomental.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)