Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Dear Alban,

I come from the Kingdom of Spain – a country that refuses to recognise yours. There’s a feeling of guilt. After all, I am the reason why your country is not recognised – I am a Catalan.

Alban Muja famously has a picture of himself in a refugee camp together with his father and the ex-president of Spain José María Aznar. At eighteen years of age, he and his family left their hometown of Mitrovica during the Kosovo war and wandered for 8 days until finding a refugee camp for Kosovars funded by the Spanish government. Muja’s father had just re-joined his family in the camp when news arrived that the Spanish prime minister was due to visit. The photograph of Muja with the ex-President now forms part of his family album which serves as a starting point for the Pavilion of Kosovo.[1]

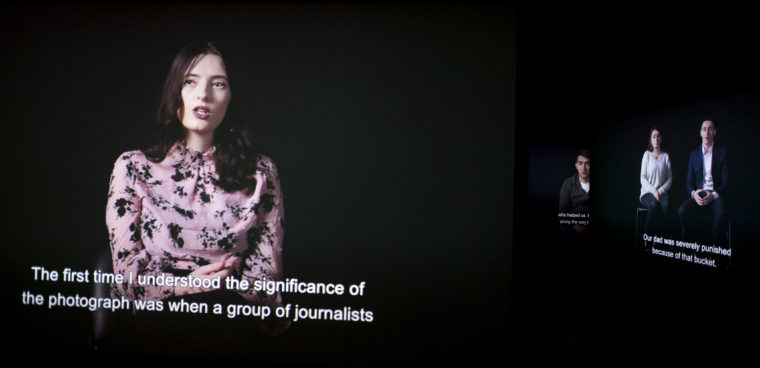

Located in the Arsenale, Alban Muja was selected to represent the fourth Kosovo pavilion curated by Vincent Honoré and Anya Harrison. Family Album is an intimate portrait of four Kosovar youths who each was the subject of famous journalistic photography about the recent war. The films are a sensitive portrait of each relating to the moment in which their photograph was taken – Besa, Besim & Jehona, and Agim. The structure of the three interviews reverses the sensationalised mediatic desire for striking and voiceless images. For an exhibition titled Family Album, photography is markedly absent. Rather, the time of the film slows the viewer down and makes a space of stillness in which a narrative slowly unfolds in a layered complexity of multiple points of view.

Muja’s project involves the people who were the unaware subjects of famous photography documentation during the war and interviews them about the circumstances of these photographs as well as how they affected the next years of their lives. Often they were infants and these years provide some of their first memories or set the stage for their now normal urban lives. The three-screen installation unfolds like a document or archive of its time while formally giving presence to the interviewees. Unlike the gesture of a single screen, the constant presence of all four characters fills the room.

Alban Muja, Family Album, 2019, three-channel HD video installation, colour, sound, time variable installation view, The Pavilion of The Republic of Kosovo, La Biennale di Venezia 2019. Courtesy: the artist and the Pavilion of The Republic of Kosovo; photograph: Arben Llapashtica

The youth of the interviewees is striking and serves as a reminder of how recent this conflict is. The film shows how Europe’s youngest country is still under construction by a generation who directly experienced the effects of war. In light of the Venice Biennale, the concept of a national pavilion is often the subject of scrutiny. Yet, while many try to reconstruct an idea of identity that breaks with the ideas traditionally ascribed, a young country like Kosovo that struggles with international recognition, the fact of being considered an equal amongst peers, places the concept of a national pavilion as a reaffirmation of the value of voice – this narrative matters.

The film describes a local phenomenon with wider implications. Now that the attention has left Kosovo, the thirst for conflict turns media attention to other refugee camps, and to other sites of conflict. Political photo opportunities serve a fleeting moment, they influence an election far away – but they remain in the family album, in a country’s collective memory. The exhibition is a display of humanism, of the microcosm that creates individual worlds, and of stories that are often erased in favour of sensational reads.

Muja declares the film as a-political. What the personal stories imply, as well as the bittersweet photograph with José María Aznar, is the consequence of the erasure of personal stories – the fury of the state, the madness of the nation. Having visited the camps of Kosovar refugees his government astutely refused to recognise Kosovo as a nation because of an absurd parallel – for fear of losing its own territorial integrity. Allied to Serbia, Russia, and Venezuela, the Popular Party disregarded the human lives this conflict had impacted in favour of winning votes and creating conservative nationalist majorities at home. It is within the sensitive structure of Muja’s interviews and the lack of sensationalism that a humanist agenda is found. As a respite from works that use sensationalist gestures built on misery – the Kosovo pavilion shows how it is possible to make respectful and sensitive art about recent conflicts. It does so by insisting that if we listened to people in crises around the world rather than selling and politicising plight, we may live in a better world.

[1]Vincent Honoré, Anya Harrison, Alban Muja, Family Album, Mousse Publishing, Milan. 2019.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)