Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Think about the Nordic countries from a Spanish perspective, leaving behind the myth of European women holidaying in Spain during Franco’s regime. Let’s travel back in time to Scandinavia in the 70s: wealth, full employment, the social democratic party in power for decades… A progressive paradise on Earth. Nordic Governments had sped up, then, one of the great operations of individual liberation in history: no (elder, young or sick) person should depend on anyone to survive. Any kind of affective relationship between two people should only be out of love, since the state, by means of financial aid, replaces family and friends as a protection network. That is what the documentary The Swedish Theory of Love (Erik Gandini, 2015) is about… at first, because this immaculate idea had an unexpected effect that became the Nordic epidemic: loneliness. Perhaps this is what Martí Manen, curator for the tenth edition of the Nordic Biennial Momentum called The Emotional Exhibition, referred to when he told the press conference: “Let’s talk about Scandinavian pain.” And it reminded me of the piece A Lot of Sorrow by Ragnar Kjartansson, whose work generally revolves around the Nordic tendency towards drama, despair and melancholy that also had a strong influenceon Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s avant-garde works, or Swedish film-maker Ingmar Bergman. Well, a large part of the curators’ work was looking through the last 10 editions to bring back artists and works —making half the exhibition, approximately— and it turns out Kjartansson is one of them, with a documentary photography of the piece Scandinavian Pain exhibited in 2006. The same happenedto Dutchman Gabriel Lester’s film The Blank Stare. Characters look intensely out of shot without blinking or talking. It is in their stare where the audience empathizes with their rage, fear, suspicion or delirium, identifying those emotions within ourselves: “I understand you, I feel incoherent, sad and lost, too.”

But let’s continue with the Scandinavian dream, a part of the ambitious Million Programme implemented between 1965 and 1975 by the Swedish government is Råslätt suburb, located in the centre of the country. This is where the film with a feminist perspective In Purple by Joanna Billing is set, a film dedicated to the hip-hop group Mix Dancers and the self-managed dance school for girls with the same name. The group fights for the concession of outdoor public spaces for dancing, generally assigned to other traditionally masculine disciplines like football or basketball.

The star curator of the 90s, Hans Ulrich Obrist, said at the exhibition Nuit Blanche in Paris in 1998: “In the 90s, we have witnessed the creation of art centres that need to express their own realities. Copenhagen, Helsinki, Oslo, Reykjavik and Stockholm along with Bergen, Malmö and Oulu contribute to this trend with a burst of creativity that seems to show a real ‘miracle.’” Regional investments like Momentum started in Moss, Norway, and this “Nordic miracle” is mentioned in the first paragraph of the first catalogue. The first Biennial took place the summer of 1998, and it included most artists often regarded as part of the aforementioned Nordic miracle, like Olafur Eliasson who is one of the artists brought back for Momentum10. What initially was plannedto be a Nordic festival of contemporary art became a biennial, and nowadays it isn’t only a Nordic matter, but an event with international artists.

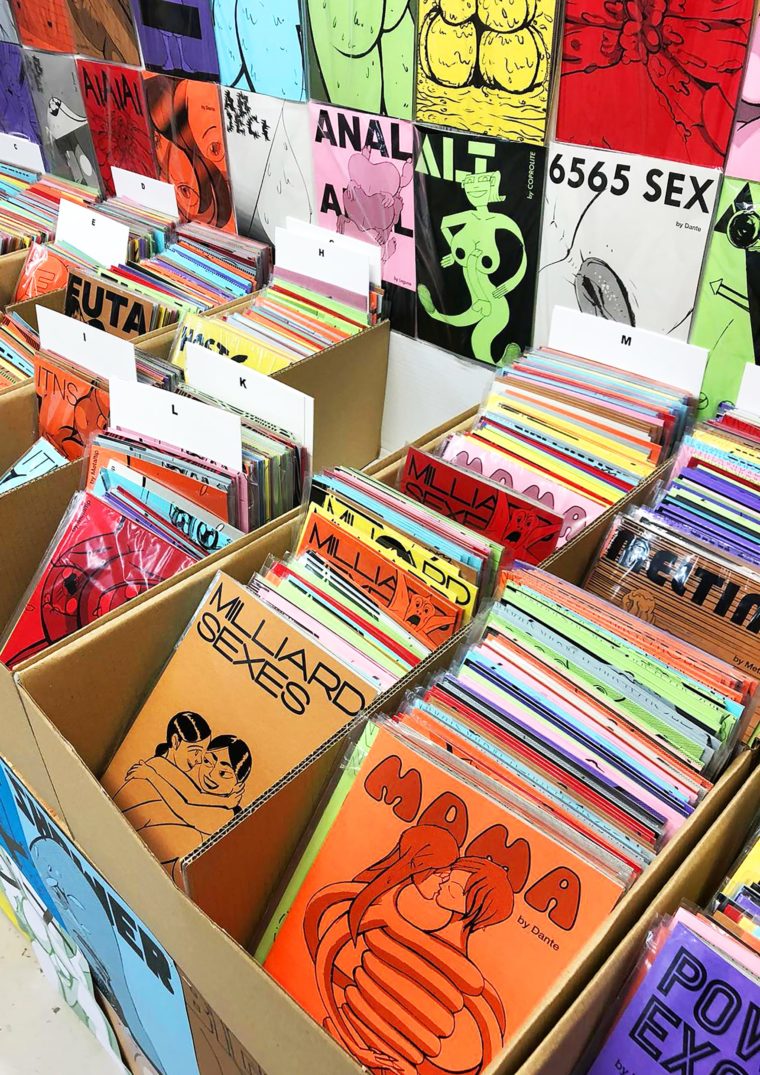

It is Momentum’s anniversary and that has sentimental value. The fact that emotions are the centre of the exhibition is very appropriate for the times we live in, a moment where traditional, dominant power structures collapse, and oppression systems are given more visibility. Repressing emotions is one of the forms of power wielded by western rationality for centuries. And it’s particularly interesting that “The Emotional Exhibition” takes place in Norway because Protestants who live in northern Europe know that emotions don’t exactly come to the surface very often in these parts. It is also noteworthy the connection between contemporary art —and its essential conceptual trends— and emotions. Art self-validated by the concept, the rationality, in short, by the white man’s control. For a very long time, emotions have been associated to a “minor” art, relegating it to women and people from non-western cultures who normally used their bodies and/or nature and were, by definition, primitive and sensitive. One of the best examples of dissension, of visualizing other bodies, sexes, genders, is the large collection of underground comics with a sexual theme and fetishes by Francesc Ruiz in House of Fun, an area of radical freedom that explores the limits of representation through drawing.

Francesc Ruiz. Photograph courtesy of Momentum10

And, unfortunately, though the almost-perfect, Nordic social democratic model wasn’t imitated by other countries, other Nordic groups are certainly prominent in our daily lives, and I’m not talking about tattooed Vikings ravaging Europe’s arts centres, whether it was 11th century monasteries or 21st century hipster cafés, but global capitalism and —Swedish— multinational companies like Ikea or H&M, with their slogans about good design and fashion for everyone. This is why I can’t help but admire Pepo Salazar’s installation named Frozen.Frozen is an affiliated attack against mass consume encouraged by multinational commercial companies and an ironical and effective portrayal that shows the disadvantages of homogenization. Recognition and closeness are feelings used by capitalism, setting up the same clichés in very different and distant places: rebuilding monuments in other countries and cultures, having the faces of famous singers and footballers plastered over all kinds of objects, etc. Iconography originated from a consumer society and fake proximity are the essence of Salazar’s work: badly-edited pictures of fast food, meat advertising, Chinese red lanterns or beds from Ikea with quilts patterned with the faces of famous football players.Frozen masters perfectly this double meaning of closeness and distance.

Pepo Salazar. Photograph courtesy of Momentum10

Pauline Fontdevila. Photograph courtesy of Momentum10

The city of Moss, playing host to the biennial, is located in the heart of the northern region, at the same distance —an hour away by car— from Oslo and from the Swedish city of Gothenburg. With 50.000 inhabitants, it fits perfectly with the landscape of fjords and suffers per se the consequences of the post-industrial era, gentrification and globalization… Pauline Fondevila takes the fjord as her stage for the performance that is part of a “highly” lyrical body of work called The Promise by the Sea. The performance was in partnership with a group of sailor kids that defied the ocean in twenty sailing boats whose sails have situationist slogans for May ‘68, a historical moment where emotion played a crucial role in individual actions. This anarchic feeling continues with the piece located in Kunsthall Momentum, where a pop song written and performed by her plays to celebrates her solo escape (in a more or less metaphorical sense) from social limitations.

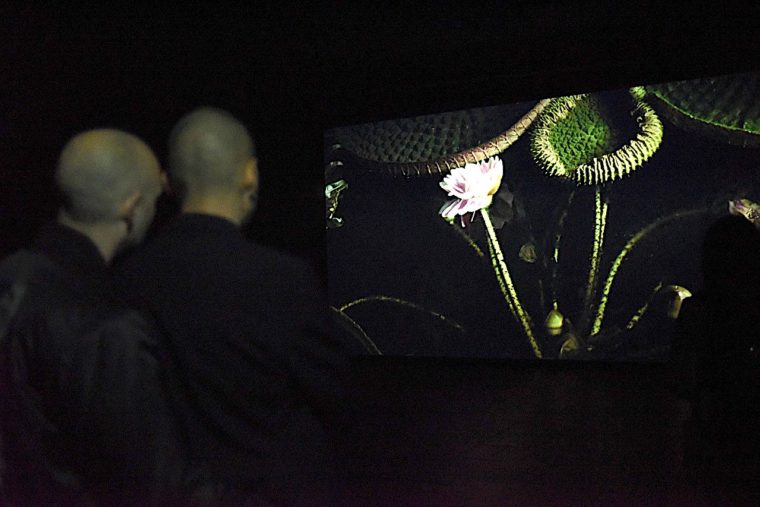

Salla Tykää. Photogragh courtesy of Momentum10

Ilkka Halso. Photogragh courtesy of Momentum10

The connection with nature and the emotion that it brings is very important in Scandinavian identity. Momentum10 is especially harmonious with nature and the environment. Performances on the beach by the Norse artist Ina Hagen, the slow-motion video Victoria by Finnish Salla Tykää about Queen Victoria’s water lily, or the pictures by Finnish Ilkka Halso, are all works that have been brought back from the 2009 and 2004 editions, respectively. In the last one, the landscapes are interrupted by disused structures symbolizing the anthropocentric society we live in. The pictures are part of the collection Museum of Nature, in which Halso suggests using advanced technology in order to protect nature against pollution and overpopulation. These works are symptomatic of the respect and veneration Scandinavian people feel towards nature.

Finally, if there is one lesson we should learn from Momentum10, it is that emotions are never easy to come to terms with, neither in life nor in art. The pre-inauguration of Momentum took place June 7th at the same time as the music festival Lyse Netter (Bright Nights), and the thing is, in the Nordic summer light becomes sort of a trap, a day that refuses to end. Just that poetic art of light cancelling the night out makes one feel emotional.

MOMENTUM10.The Emotional Exhibition.

Until October 9thin Kunsthall Momentum, Galleri F15 and other locations in Moss, Norway.

(Highlighted image: House of Fun. Francesc Ruiz. Photograph courtesy of Momentum10)

María Muñoz-Martínez is a cultural worker and educator trained in Art History and Telecommunications Engineering, this hybridity is part of her nature. She has taught “Art History of the first half of the 20th century” at ESDI and currently teaches the subject “Art in the global context” in the Master of Cultural Management IL3 at the University of Barcelona. In addition, while living between Berlin and Barcelona, she is a regular contributor to different media, writing about art and culture and emphasising the confluence between art, society/politics and technology. She is passionate about the moving image, electronically generated music and digital media.

Portrait: Sebastian Busse

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)