Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The eco-social crisis that we have been going through in an increasingly conspicuous way over the last decades, the severity of which has increased due to a pandemic closely related to the environmental imbalances caused by vertiginous globalization, has placed large cities in the spotlight. Cities with uncontrollable growth have rightly been accused of deploying more and more predatory devices of voracious consumption without worrying about planetary wellbeing, generating instead quantities of toxicity that are impossible to process at a reasonable rate.

Peasant movements demand sovereignty over the territories subjected to the mass industrialization of food production that is demanded by the big cities. The struggles in defense of the land denounce how the extractivist policies that devastate entire communities maintain an urban energy model based on fossil fuels. Awareness is growing of how large cities are no longer compatible with the desirable principles of good living. There are those who have claimed, provocatively but also with a real objective basis, that if today’s megalopolises suddenly disappear, not only would they not be missed in terms of the reproduction of planetary ecosystems but, on the contrary, their disappearance would be immediately beneficial. All of this being true, when it comes to reconsidering the role of cities in the framework of the current eco-social crisis (what scale could be compatible with a good life and is it still possible to reverse the speed of their growth so as to not to accelerate ecosystem degradation, or if, on the contrary, megacities have to be urgently fragmented, rearticulated or dismantled, etc.), there are other aspects that are less scientific, more intangible, less quantifiable, and generally taken into account much less. One of them is the following: that cities have been an intensive site for the contradictory experience of modernity, a material corpus where the tensions have historically oscillated between the emancipatory promises not always fulfilled and the disasters often caused by modernization processes. And if cities are also, for this reason, places where we can currently contemplate, properly experience, and therefore potentially confront the contradictory heritage of modernity, surely the great extra-European historic metropolises, such as Buenos Aires, are also exceptional spaces where these contradictions are embodied today in the clearest way.

During the 1980s and 90s, contemporary art was both an instrument and a critical space in the processes of urban transformation promoted by neoliberalism, a highly extractive and minimally productive stage, surpassing the capitalist industrialization that originated modern metropolises. Contemporary art served as a prototype for the precarious flexibilization of the old figures of industrial work and as the avant-garde of gentrification, which caused displacement of the impoverished urban population with the consequent exorbitant cost of real estate and lifestyles. Art also functioned, though, as a critical testing ground for analyzing the neoliberal de-structuring of the public sphere and an attempt to rebuild it.

These were precisely the decades in which photography was fully incorporated into the expanding global art system. It was not only a mere process of incorporating photography and other techniques of technical or electronic reproducibility of the image into classical means of artistic expression. This normalization of the reproducible image in the international art system also happened for a more important reason: in many cases photography, as well as other means of reproduction of images used in accordance with the critical traditions of the history of photography, served much better to confront the contemporary complexities that took shape in dramatic urban transformations. Now that cities are at the center of the criticism of the problems associated with a growth model that has pushed life on earth to the brink of collapse, what can art do, by making use of the critical traditions of the history of photography, to face these new contemporary challenges and abysmal crises? What this exhibition attempts is to offer a synthesized model of how the history of photography allows us to observe the city as a reservoir of memories of the experience of modernity. This exhibition is a reduced-scale model of how the representations of the modern city, its postmodern permutations (quite literally embodied in the objects of Luciana Lamothe, Martín Carrizo and Sofía Durrieu, anti-monumental architectural sculptures that refer to the visual images of this exhibition) and its current terminal crisis constitute a palimpsest of contradictory memories of modernity.

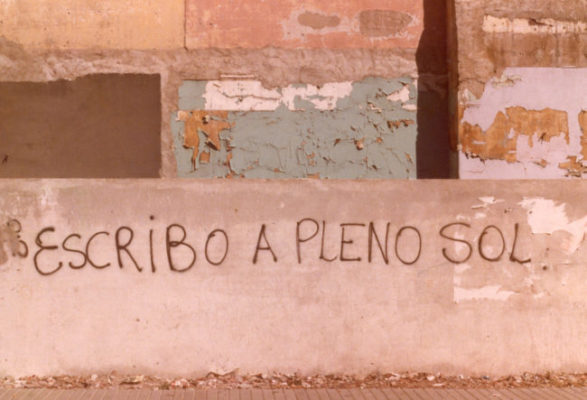

Within the countless ways in which photography has portrayed the city, this exhibition selects a few photographs and other moving images that have one characteristic in common: they are all part of the city’s imagination displayed in its usually anonymous, empty, deserted, depopulated, silent, abandoned or desolate spaces. In the critical history of photography, this image of the naked city grows out of an archetype, namely, Walter Benjamin’s reading, in his A Short History of Photography (1931), of the images of Paris captured by Atget, who “would almost always walk past the great sights and monuments, but not … the sight of the empty tables where the unwashed dishes lie … Empty is the Porte d’Arcueil in the fortifs, empty the ostentatious stairs, like the patios, or the cafes terraces; empty, as it should be, the Place du Tertre.” These images resonate strongly, in a very literal way, within the photographs by Humberto Rivas, Francisco Medail and Juan Travnik exhibited here, but also in a paradoxical way in the work of Marcos López. The photographic imagery of emptied cities strangely belongs more to the order of the “self-portrait” than to documentary, though not a self-portrait of the photographer but of the photograph itself, in the sense that these are images in which photography as a technique of the production of reproducible images is identified with the mechanized city as a large-scale device arising from its very matrix, capitalist industrialization. Photography, in other words, portrays itself through the technological city, its double. Symphony of a Great City (1927) by Walther Ruttmann is, more than a documentary about Berlin, the record of the fascination that the cinematographic apparatus feels for the metropolis, its greatest double. And just as Ruttmann’s Berlin is proto-fascist in the way in which it reproduces in the viewer a subjectivity that is at the same time fascinated and helplessly subjected to the disciplinary device both of the film director and of the factory city, Man with a Movie Camera (1929) by Dziga Vertov attempts to construct a subjectivity enthralled with the possibility that, in the same way that a film cameraman composes an emancipated body with his mechanical apparatus, so too the masses can take a revolutionary control of urban modernization, embodied in this case in a Moscow both contemporary and futuristic, projected virtually on the screen and, therefore, in the imagination of socialist subjects. (Traces of this historical complexity are collected as synecdoches in the photographs of Roberto Riverti and in the cinematographic installations of Andrés de Negri.) The photographic imagery of the emptied city oscillates throughout history between these two dystopian and utopian poles, happening both structurally and materially, beyond the manifest “content” of the images.

It cannot be by chance that, at the beginning of the 1990s, the Argentine writer Ricardo Piglia decided to rearticulate a historical model of the representation of the modern city, the novelistic “symphony” about emerging metropolises, a contemporary model of the historical cycle of those urban cinematographic symphonies. La Ciudad Ausente (The Absent City) by Piglia contains obvious nods to James Joyce’s Ulysses and, unlike the usual interpretation of these references (an interpretation that confines them to a kind of trans-historic, metalinguistic dialogue between writers fascinated by narrative experimentation) it always seemed to me that the postmodern Buenos Aires related by Piglia proposed a reflection on the crisis, in neoliberalism, of the archetype of the modern city embodied in Joyce’s Dublin, John Dos Passos’ New York or Alfred Döblin’s Berlin, that is, the metropolises that were canonically considered, during the last century, models of modernization against which to measure the developmental processes of extra-European metropolises, and that gave rise to monstrous artifacts due to their hybridity, as exaggeratedly beautiful and unique as the photographs and collages of Buenos Aires as a metropolis of Cubist or Dadaist dreams by Grete Stern (prolonged in their way by Narcisa Hirsch and Marcelo Brodsky) and of the Buenos Aires portrayed by the powerful poetics of Horacio Coppola’s direct gaze. It could be said that, in a strange way, the monumentalization of the modern city that Coppola establishes is the reference model that such apparently diverse works as those of Andrés Durán, Carlos Trilnik, José Alejandro Restrepo, RES and Santiago Porter deconstruct. For Piglia to call his postmodern Buenos Aires an “absent” city, moreover, seems like a huge contradiction, as the novel explodes with intertwined stories and characters appearing and disappearing at breakneck speed. This only seems a paradox, which we could resolve with Benjamin’s reading of Atget: “In all these images, the city appears emptied out, like a house that does not yet have a new tenant.” Modern portraits of the emptied city are not the opposite, but instead are the reverse or the other side of the teeming, bustling, dizzying, emerging metropolis. These aren’t so much images of an absent or deserted city, but rather those of a halted city, full of a latent power, perhaps because it is “not yet” inhabited due to some unknown cause (or one that we already know) but which is in any case on the verge of exploding.

In an unexpected way, in the historical arc that spans from the original emergence of the industrial metropolis to the terminal crisis of the modern city, the image of an emptied-out city folds in on itself: Atget’s photographs of Paris have been updated time and again in each of the countless mental or digital images reproduced globally during the months of rigorous confinement that we suffered at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Representations of apparently empty, ghostly cities, but which those who lived in them, confined, knew that they were inhabited and traversed by forms of labour essential for social reproduction and for the maintenance of threatened life; invisible, undervalued, underpaid social relations that, in any case, were there, sustaining in a contradictory way our now halted cities on the verge of exploding. All the imagery contained in the reduced-scale model that constitutes this exhibition is measured against the same matrix that underlies this double historical representation, at both ends of this historical arc that, however, unexpectedly coincide within a fold in time: the empty city of Atget, the empty city of the coronavirus. They are unexpected images of our contradictory memory of the city, which help us to project onto them the imagination of a possible new city, of a new urban and global public space located in a world beyond the terminal crisis of the metropolis. A potentially new city, latent otherwise.

(Featured Imagen: Narcisa Hisrch, Sometimes everythings shines | A veces todo brilla. C. 1979-1980. Courtesy Rolf Art)

*Wall text for the exhibition Ciudad invisible, at the Galería Rolf Art in Buenos Aires. The exhibition can be seen both in person and virtually, with works by Horacio Coppola, Grete Stern, Humberto Rivas, Marcelo Brodsky, and a long et al.

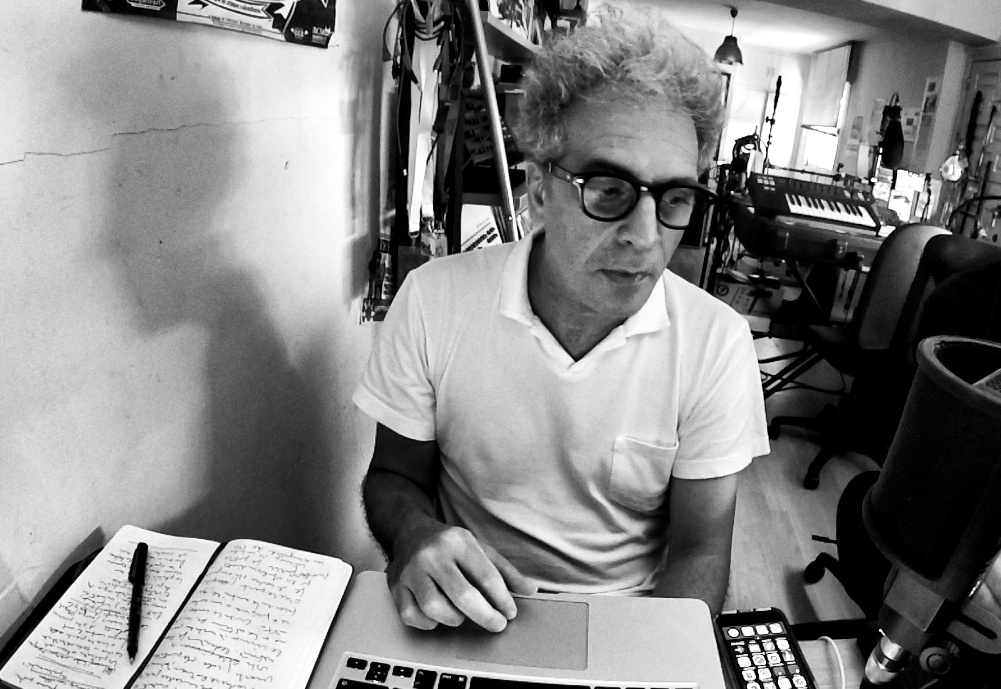

Marcelo Expósito (Puertollano, Spain, 1966) is an artist and cultural critic. His publications include Walter Benjamin, productivista (2013), Conversación con Manuel Borja-Villel (2015) and Discursos plebeyos (2019). His work has been the subject of recent retrospectives at La Virreina Centre de la Imatge (Barcelona), FICUNAM 11 (International Film Festival of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma of Mexico) and the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico City. He has also exhibited in international exhibitions and institutions such as the Aperto ’93 of the Venice Biennale, the 6th Taipei Biennial, the Manifesta 8 European Biennial of Contemporary Art, the Bienalsur in Buenos Aires, the Steirischer Herbst festival in Graz, the Ibero-American Theatre Festival (FIT) in Cadiz, the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid and the Centro Galego de Artes da Imaxe (CGAI) in A Coruña. He has been involved in social movements for democratic radicalisation for three decades and has held the posts of secretary of the Congress of Deputies and deputy in the Spanish Cortes Generales during the 11th-12th legislatures (2016-2019). marceloexposito.net

Photo: Andrés Garachana

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)